KRAZY! The Delirious World of Anime + Comic + Video + Games + Art

The challenge of presenting a broad overview of visual culture’s more populist forms—comics, animation, video games, etc.—is that there’s a wider audience to piss off. Within the intelligentsia and the world of nerd culture—teenage and adult alike— both circles come embedded with their own strident criteria and passionate attention to detail. From the outset, an ambitious exhibit like “KRAZY!” stands to incur the disdain of growed-up graphic novel readers and the wrath of basement dwellers on Internet message boards: the politics of inclusion and omission will invariably follow a show of such ambitious scope.

Enough energy has been spent on legitimizing, say, video games and graphic novels: the clarion call of “It’s a sophisticated, trenchant form of art/literature and not just for kids anymore!” has echoed loudly enough that the latter has netted book of the year awards (see Time magazine honouring Alison Bechdel’s heartbreaking Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic), while the video game industry is currently giving Hollywood blockbusters a run for their money.

Takashi Okazaki, Afro Samurai, fi lm still, Studio Gonzo, 2007, DVD, 5 episodes: 25 minutes each. © 2006 Takashi Okazaki, Gonzo/Samurai Project.

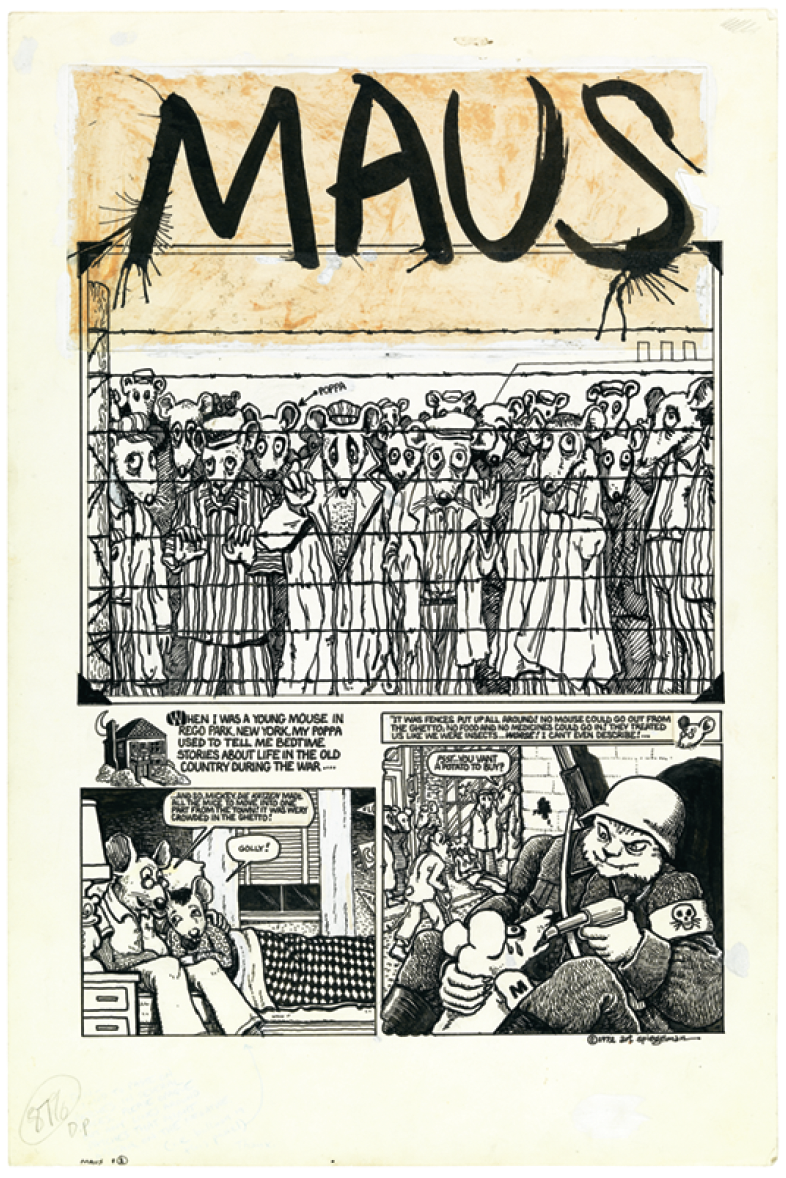

What’s interesting about “KRAZY!” is its attempt to appeal to different crowds—the stereotypical fan boy, the “serious” aesthete, and the arm’s-length gallery goer in search of edutainment. Despite some curatorial missteps, it’s a highly enjoyable, if uneven, exhibit. Spiffily laid out by Japanese anarchitects Atelier Bow-Wow and team-curated under the headings of Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, Anime, Video Games and Contemporary Art, the two-floor show is exhaustive enough to forgive the exclusion of, say, R. Crumb, Marvel and DC Comics or whichever genre-axe one could bring to grind. Ostensibly separate, the Comics area flows into the Graphic Novels section, employing a formula of presenting process and final product. The heavy hitters are there: vintage original panels by Milt Gross and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat on yellowed newsprint appear with seminal works like co-curator Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-winning Maus and Chester Brown’s historical Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography saga, while finished segments and roughs by contemporary cartoonists like Kim Deitch, MAD Magazine’s Harvey Kurtzman and Dan Clowes show the laborious and even thankless amount of work that goes into a narrative form often consumed all too quickly. Presenting whole installments behind glass may raise a work’s status and aura as bona fi de art object, but it doesn’t lend itself to actual reading. It is great, though, to see the blue pencil and eraser marks, the Zip-A-Tone, liquid paper and cut-and-paste construction of work by favourites like Chris Ware (who approaches the Bristol board with a master draughtman’s sense of layout and design) or co-curator Seth (who operates more as historian and archivist of the form itself). If anything, the works behind glass act as a reminder that some things are still reserved for an afternoon off with the art-object in book form resting on your lap, preferably with a cup of coffee.

Marcel Broodthaers, Ombres chinoises, 1973–74, detail, slide projection, 35mm slides. Collection of the Estate of Marcel Broodthaers. © Estate of Marcel Broodthaers/ SODRAC (2008).

With a history that stretches back to Hokusai, Manga is an important and lucrative aspect of Japanese Pop culture. Given the history of the form, its own showcase seemed lukewarm: little sense of the form’s pre- or post-war lineage is given, replaced by a focus on more contemporary and Pop titles. Although Mamoru Nagano’s attention to detail and Junko Mizuno’s “cute to kill” female characters where men take the backseat were appreciated, Takashi Okazaki’s Afro Samurai is no just replacement for Barefoot Gen, Keiji Nakazawa’s distinctly political and heart-wrenching post-Hiroshima survival tale or the sizeable corpus of original master Osamu Tezuka. At least some of these key works can be found on the shelves in the gift shop. And since it’s a family event, Hentai, the darker, pornographic side of Manga and its attendant subgenres (guro, lolicon, tentacles—Google at your own risk) are omitted, despite its hushhush prominence in Otaku circles.

The principle of exclusion did not completely hinder the effect of the Anime wing, however. I stepped into geek heaven. Laid out like a Caligari-esque maze of multiple projections at odd angles, it offered a stroll inside an Otaku’s brain in the midst an Adderall bender. The combined din and visual stimulus of multiple screens presented anime’s tightly reigned yet dynamic chaos that live-action Hollywood blockbusters can only hope to reproduce.

Junko Mizuno, Pure Trance: Kaori the Nurse. Produced by KidRobot, 2007, plastic, pigment. © Junko Mizuno, 2007.

What’s interesting here is the choice of content. Common themes like post-apocalyptic Tokyo (the hallucinatory chaos of Akira), machines meeting mankind in battle (Mecha Suit dogfights in Ichiro Itano’s The Super Dimension Fortress Macross) and views behind the Freudian trap door (Satoshi Kon’s brilliant mind-bender Paprika) offered a peephole into a nation’s collective psyche. The fires that wiped out Edo-period Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, plus the earthquake anxiety of a tightly coiled technophile society that, as legend goes, is built on the back of a sleeping dragon, reverberate in these works, if not readily apparent on the surface. I was disappointed that Ghost in the Shell didn’t make the cut, as there are enough technological, bioethical, post-human and philosophical considerations braided into Masamune Shirow’s dystopian cyborg thriller to warrant a thesis paper or four.

After the bombast of the Anime maze, the selection in the Western animation wing felt par for the course—lots of kids glued to plasma screens watching Over the Hedge and Pixar’s Toy Story while the grown-ups contemplated framed storyboards and original cels, including the 1914 Disney precursor, Gertie the Dinosaur. But who could get mad at Dumbo? Or Wallace & Gromit? Or Gerald McBoing Boing?

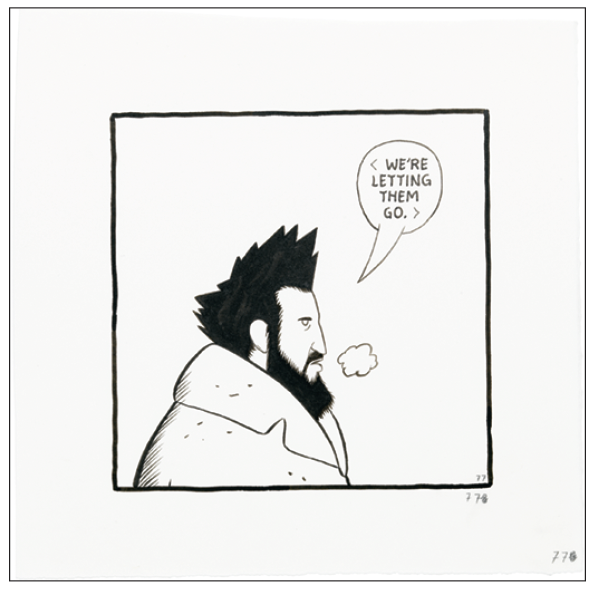

Chester Brown, Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography, 2001, panel 77, fi nal drawing, ink on paper. Collection of the artist. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. © Chester Brown, 2002.

It seemed like Atelier Bow-Wow’s contract ended at the second floor, since it lacked the punch and engrossing downstairs layout. Contemporary Art and Video Games had almost too much breathing room among larger-scale installations, although the huge cinema space that rotated some of the full-length titles featured downstairs was a nice touch if you’re playing hooky on a weekday afternoon.

Sadly, the Contemporary Art portion of the show seemed either forced or tacked-on, trying too hard to bridge an assumed cultural gulf to the point of being pedantic and predictable. I’ve always wanted to see Broodthaers’s work in person, and the 1973–74’s slideshow Ombres chinoises dealt with issues of image, content and representation through 80 images taken from his surrounding culture, like a Google image search a few decades removed. On its own or as part of a solo retrospective, it would have made more sense, but given the weighty conceptual play within his work, it wasn’t quite a fit.

The same could be said for Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe’s ambitious No Ghost Just a Shell project. Despite the participation of international contemporary art heavyweights like Rirkrit Tiravanija and Liam Gillick, their pre-purchased readymade anime character whose function it was to mouth other artists’ words in a series of multimedia works fell flat. Essentially a digital ventriloquist’s dummy or marionette that investigates mediation, copyright, identity and agency, the works were not only too heavy-handed but, in all honesty, looked ridiculously dated. Despite its being an ongoing and apparently important project, it seemed stuck in the ’90s: a pre-Web 2.0 CGI artifact of techno/rave visual culture that was given more importance than it actually merited.

Art Spiegelman, Maus, 1972, page 1, fi nal drawing, ink and Zipatone on Bristol board. Collection of the artist. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Christian Marclay and Cao Fei made up for it, though. Marclay’s large-format Onomatopoeia collages of various “Bang!”s, “Pow!”s, “Kraaak!”s and “Aaaaarrgghhh!!”s ripped from comic books fit well with his practice of recombining Pop-culture effluvia, and it was an interesting departure to see something that didn’t involve old records.

Fei’s 2004 video COSplayers was given an opportunity to shine, and like Broodthaers’s piece I was glad to finally see it in person. Cosplay (short for “costume play”) is similar to Trekkie culture in spirit and fetishistic attention to detail, where anime and video game freaks dress up, gather and pose as their fantasy heroes. It’s quirky and neat, if they’re adolescents.

In Fei’s eight-minute video, he highlights the tensions between fantasy, identity, escapism, and societal and cultural norms. There’s a whole lot of Freud (or maybe Lacan or even Dick Hebdige) going on in the video in terms of appearance, fetish and fantasy, showing the gulf between the real and idealized self. Viewing it, there’s a constant push-pull: it’s entertaining and funny in a wink-wink “Nerd Pride” kind of way, but conflicted and sad at the same time.

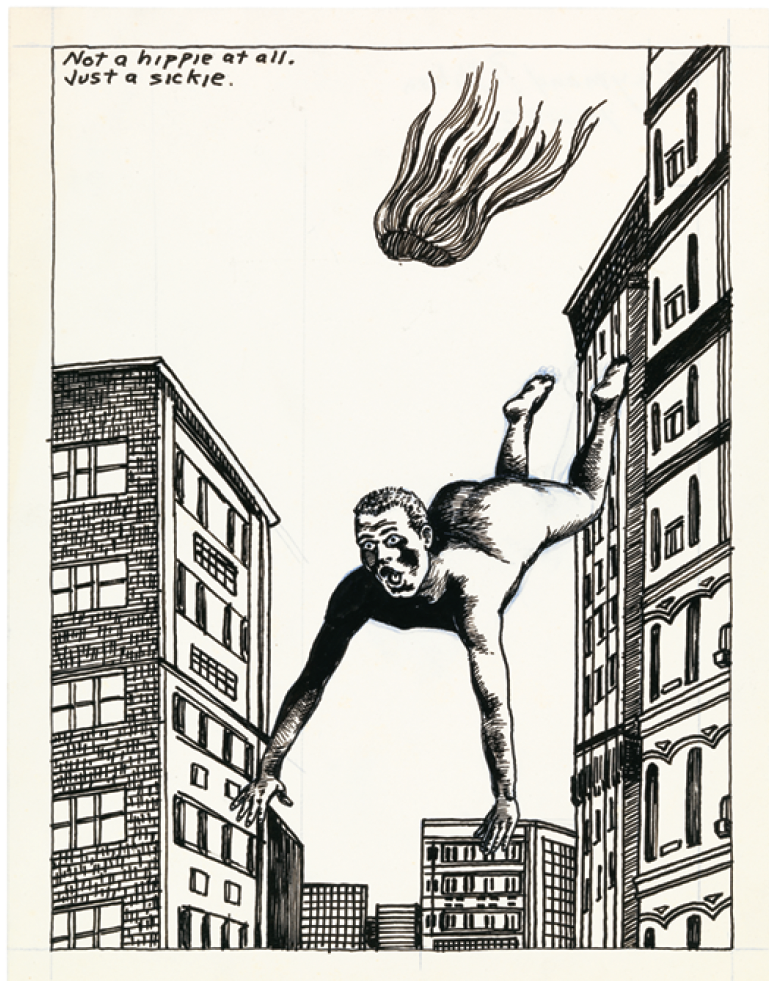

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Not a hippie), 1982, ink and coloured pencil on paper. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery.

For older gamers like me who grew up on arcade tokens and Atari consoles, the video game section presented its history in a straightforward manner: Pac-Man, Super Mario Brothers and The Sims™ share wall and monitor space, while a 20-screen grid from first-person-shooter Quake plays out its gory hyper-violence in surround sound on an adjacent wall. The layout of the space seemed awkward, but the real curatorial misstep here is that the moral panic that follows video games today was not addressed. Titles like Bully, Manhunt, the latest Grand Theft Auto are treated by the morally upright like a precursor for the next Columbine and Al-Qaeda attack combined. Like comic books in the ’50s or Heavy Metal in the ’80s, the kind of scrutiny and outrage that dogs popular and visual culture is an interesting cultural barometer, in terms of society’s need to fi nd scapegoats. You have to ask: what line separates the anvil falling on Wile E. Coyote’s noggin, from the violence you see on prime time TV?

Come to think of it, that was the downfall of the show for me—what was absent was most noticeable in terms of questions and cultural currents that could have been approached. In presenting such a broad range of genres you couldn’t expect a show like “KRAZY!” to be either a full win or lose. Weighty theoretical concerns could be projected on the work, but any formal analysis of comics, cartoons and video games would have fallen flat on its face—and with a satisfying WHOMP! I think the curators knew which audience they had in mind, and the guiding principle for looking at “KRAZY!” is that if you’re annoyed (like I was—briefly) that, say, Los Bros Hernandez’s comic series Love and Rockets isn’t represented, that’s okay. Ten bucks says if you’re enough of a fan to check out the show, the work is on your bookshelf already and probably sealed in plastic, acquiring collector value. ■

“KRAZY! The Delirious World of Anime + Comics + Video Games + Art,” curated by Bruce Grenville, Tim Johnson, Kiyoshi Kusumi, Art Spiegelman, Seth, Will Wright and Toshiya Ueno, was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from May 17 to September 7, 2008.

Christopher Olson is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings, Vancouver Review and Front magazines.