Kota Ezawa

Aeons ago in my foundation year of studies, one of my first projects was to pick an Old Masters painting, find the lines and symmetries in its composition, trace out and then fill in the resultant geometric forms. What made the project interesting to me was the reduction of a canonized, possibly sacrosanct image into something else. What was meant to be a simple study in form, perspective and composition became a symbolic upending of art history: an opening up that came from turning something on its side and adding my own gesture to it. I wasn’t reinventing the fountain/urinal, but for about five minutes, it seemed pretty close.

Much has been learned about appropriation since then. A key aesthetic and conceptual strategy in contemporary art, it’s a winning formula, provided you add your own twist. Scanning Warhol’s Brillo boxes, the Situationist International, Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince’s Marlboro Men, and ending up at hip hop, nicking something from the surrounding culture and churning it through the signification grinder has become so de rigeur that at times its effectiveness seems questionable. Especially now in our current media-scape: thanks to CNN, the jpeg and the interweb, events seem to be tailored for the larger spectacle. From Desert Storm, Columbine, 9/11 and the rambling manifesto explaining the recent horror at Virgina Tech, the common media image, whether iconic or in passing, has viral power in the way an event is received and absorbed. Everything depends on how it’s presented. Since time now happens in news flashes and on-the-hour updates or can be viewed, ad nauseam, via sites like YouTube and LiveLeak, the revolution may not be televised, but someone will post a cell phone video that will spawn a thousand blog entries, even though some people will still be too busy watching slo-mo loops of towers one and two collapsing to half-convince themselves that something fishy went on.

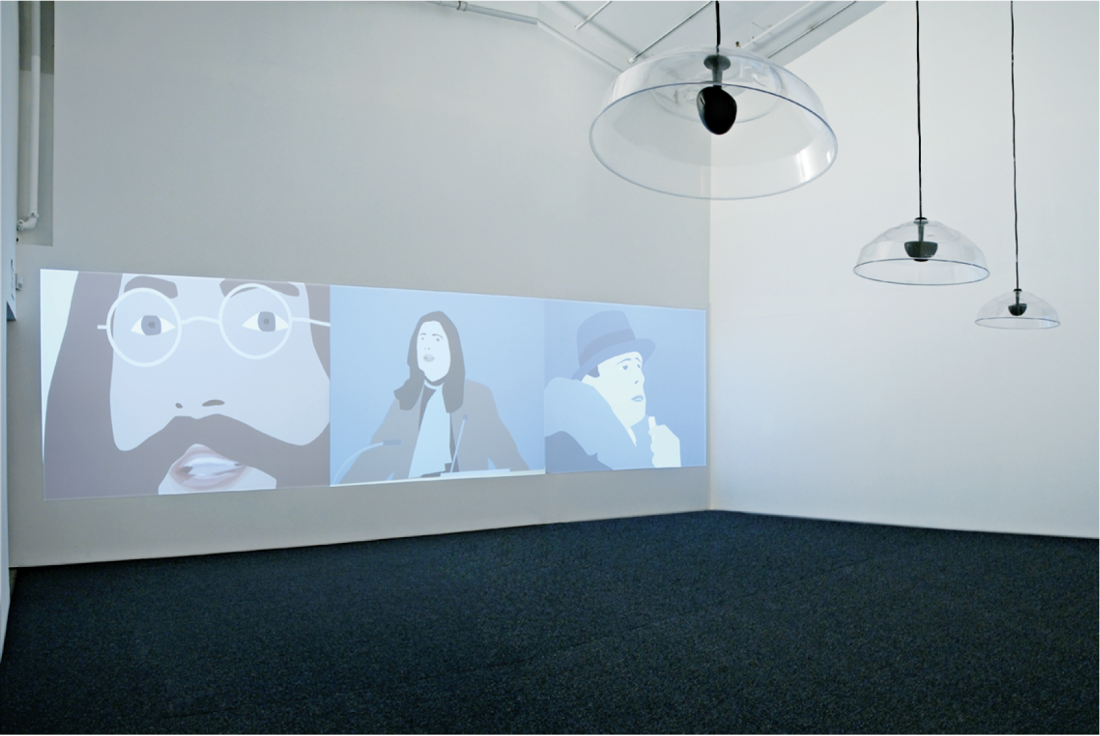

Kota Ezawa, Lennon, Sontag, Beuys, 2004, installation view, Charles H. Scott Gallery, Vancouver, video projection. Photo: Scott Massey.

In short: history and memory become malleable when an event is mediated. The stuff of culture— mass or otherwise—seems even more fertile for the artist who remixes it, now that inspiration is a Google search away.

That said, Kota Ezawa makes good-looking work, while using appropriation’s reliable strategy. He has yet to jump fully into the sea of digital clutter like some artists, but, rather, uses iconic images from photography’s history, attempting to tweak their built-in indexical and taxonomical functions by re/presenting each image as a case study unto itself. Photography is a self-reflexive medium to begin with, so for Ezawa, who distils photographic and moving images through vector-based software, like Adobe Illustrator, down to a flat, almost South Park-esque shell for his aquatint etchings, paper cut-outs and animated videos, it seems perfect that he takes on its own history.

By taking the stuff of reportage (Matthew Brady’s Civil War dead, a mushroom cloud reduced to a cartoonish marshmallow puff), and the stuff of art (Jeff Wall, Cindy Sherman), Ezawa’s eye candy interrogates the credibility of each image via its construction and dissemination. By examining the taken-for-granted authority that a photograph confers via issues of representation and construction of meaning, Ezawa’s work is packaged nicely enough that the ideas don’t come off as too stuffy or austere. It’s the once-removed familiarity coupled with friendly colours in the work that draw you in.

Kota Ezawa, Lennon, Sontag, Beuys, 2004, detail. Courtesy the artist, Murray Guy, New York, and Haines Gallery, San Francisco.

What stood apart from the etchings and paper studies in the exhibit was The History of Photography Remix, where his works are collated into an ideal medium: the slide show. Whether used by your uncle to take you minute-by-minute through his recent vacation, or more commonly as a pedagogical tool, the slide show, like film, is slowly being rendered obsolete by newfangled digital means.

Here, Ezawa presents a timeline of the image, each with its own associative and impressionistic weight: from Fox-Talbot’s salty photogram experiments and the advent of the X-ray (photo as taxonomy), to the 3-D movie crowd’s uniformity (Life magazine meets Situationism and Society of the Spectacle) and, with a wink and a nod, Nan Goldin (known for using the narrative slide show as part of her practice)—the reading of his work depends on the viewer’s relation to visual culture. Those versed in art history will recognize luminaries like Diane Arbus and the Bechers, while others will see iconic news images—Marilyn Monroe’s last photo shoot, Patty Hearst’s bank heist or Hanns-Martin Schleyer held captive by the Baader-Meinhof gang). Each image becomes a cue, an icon to click on to access our collective hard drive, whether we were there for it or not.

Lennon, Sontag, Beuys, a three-channel video installation, acts nicely as a postscript. Like his signature take on the OJ Simpson trial, Ezawa distils footage down to gestures and facial expressions. Little detail exists but for Lennon’s earnest stare while being grilled by reporters at the bed-in for peace, Sontag brushing hair behind her ear at the lectern while discussing the representation of suffering and Beuys’s, well, being Beuys while lecturing on social sculpture. Their messages come through clearer, cutting through the simultaneous cacophony as you begin to isolate each screen’s dialogue. These elements play off each other like a DJ mix with a broken crossfader, and fit into what Ezawa calls “visual hip-hop.”

The History of Photography Remix, 2005, Charles H. Scott Gallery, 35 mm slide projection. Photo: Scott Massey.

In “Late Arrivals,” a catalogue essay written for the Walker Art Center’s “Painting at the Edge of the World,” Daniel Birnbaum asked an interesting question: “Can today’s repetitions be interpreted as critical appropriations of previous aesthetical models in the name of a genuine avant-garde tradition, or has today’s art finally succumbed to the ongoing recycling of fashions and style?”

Whether by accident or by design, Kota Ezawa manages to do both. There is a strong graphic element to all his work that belies its conceptual rigour. Hyper-stylized and simplified, it seems to reflect the hazy rotoscoped stills in the mental rolodex, but there’s a Pop cultural short-circuit at work too, in how they look like they could be shilling the latest MP3 player or limited edition sneaker in any bus shack or hipster periodical of choice. I have a sense that this is part of Ezawa’s agenda—mixing Pop and politics—creating what Birnbaum calls a “temporal loop,” where memory, history and representation are braided, and the actual event remains just that: an event, resting in the past, and constantly reinterpreted for the present. ■

“Kota Ezawa: The History of History,” curated by Cate Rimmer, was exhibited at the Charles H. Scott Gallery in Vancouver from March 23 to April 22, 2007.

Christopher Olson recently had visual work published in Front and Pyramid Power magazine and hanging at Headbones Gallery in Toronto.