Kim Neudorf

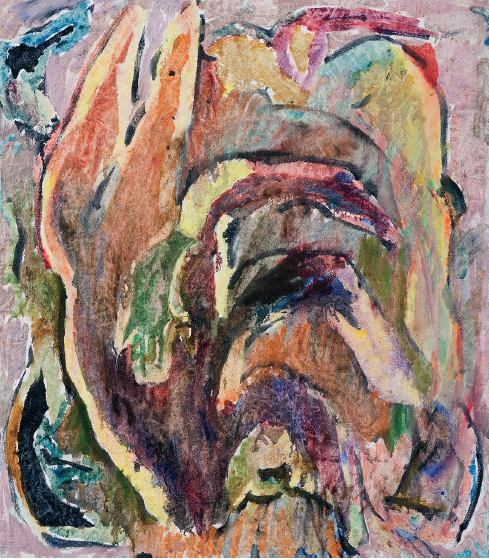

Kim Neudorf, Untitled, 2017, oil on canvas, 22 x 25 inches. Courtesy of DNA Gallery, London, ON.

Kim Neudorf’s show of paintings at DNA Artspace in London, Ontario, this past spring was accompanied by an online text collage entitled Swarm, which the artist and a colleague, Liza Eurich, had crafted. In the run-on collection of philosophical passages and aphoristic pieces by the pair, there is a curiously edifying insertion from Wikipedia they titled “Hostile Translations.” It reads: “The original famous phrase of Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka, ‘The whole is other than the sum of the parts’ is often incorrectly translated as ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’, and [is] thus used when explaining gestalt theory, and further incorrectly applied to systems theory. Koffka did not like the translation. He firmly corrected students who replaced other with greater.” This bit of information not only served to amend my thinking about a proposition I have more than once stumbled over, but it invigorated my interest in writing this piece.

Neudorf’s quietly gorgeous and intelligent works were presented in a show that both supported and belied the affect of the individual pieces. Admittedly, this is often the experience of seeing artworks and perhaps especially abstract paintings in exhibitions. In light of this, I found myself pondering the question, “How do we look at shows of contemporary painting?” Not such an urgent query, but one worth thinking about.

I shall begin here in a way that could risk accusations of esotericism by plainly describing my experience looking at Kim Neudorf’s show. The main-floor gallery space at DNA, with its polished floors and cool lighting, is a place that seems well suited to contemplating artworks. In Neudorf’s exhibition, this gallery holds six coloured canvases, which serve as elegant disruptions of the white walls. Their rhythmic placements present us with a set of “incidents” in an orderly arrangement, and this set-up is orchestrated so that beautiful works enliven the expansive, colourless surroundings.

Certainly, to encounter the pieces individually also becomes necessary. In that regard, the paintings are “one thing after another,” to paraphrase one of Lawrence Weiner’s famous conceptual art text pieces. We look at one and then replace it in our field of vision with the next. In this lower gallery of the two at DNA, the paintings on display are medium format, so they occupy the walls with a measure of balance: each is roughly the area of a human body. On the upper floor of the gallery, where the space is much larger, the additional eight works are smaller in scale (about the size of a head), and appear quite diminutive in relation to their surroundings. This draws attention to the fact the smaller works speak quietly through force of colour in the larger room. By contrast, when the paintings are larger, relative to the scale of the gallery, the colour is more insistent.

I haven’t mentioned the marks and shapes on the surfaces. Put simply, they are larger and more activated on the bigger paintings than on the small ones, and are thus livelier within the space of display in the case of the former. In the lower area, the colourful rectangular ruptures are festooned with often-agitated strokes that emerge from the paintings as if in an attempt to take over the room. In the upper space, the marks on the paintings pull back, as if to forever remain caught within the modest rectangles.

To think further about how we engage such works in an exhibition, and about whether the whole is indeed other to the sum of its parts in such contexts, I want to look closely at a few pieces. To do so, I need to note the fact that the works are all referred to as Untitled, 2017. This in itself is unremarkable, but it does leave the writer to develop a shorthand language to talk about individual pieces (i.e., “the pink blobby one”).

It is instructive to discuss two of the larger paintings at the same time. One has a “fuzzy yellow” area in the upper left, and the other has numerous black markings that are rarities in Neudorf’s vocabulary. I’m interested in these works together because they share an investment in calligraphic marks, but operate in spatially different ways. The one with the fuzzy yellow area that appears as if it might be being consumed by mould has some remarkable letterlike forms that float just in front of various patches and veils of colour. A competitive play between thin, overlapping planes and delicately scrubbed zones that dissipate is playfully engaging, yet the calligraphic marks that also hover about provide an exhilarating tension. There are but few suggestions of anything pictorial here, save for the garden-like allusion the painting itself makes. For me, the work’s greatest strength is that it elicits within a shallow and sometimes confining context the idea that it is possible to breathe in numerous ways: heavily, lightly, quickly or slowly. The work with the black lines has edges and folds that don’t occur in the other piece described. So, while the actual painterly approach employs some similar moves (i.e., thin washes meet rough patches, and the glowing palette is muted), the piece has a structure that manifests an organic architecture, which produces a quality of “thingness.” There is even a sense of figuration here that gives way to what I would describe as “faciality”— as if the work is looking back at us. The black marks in the piece play off the delicacy of the running colours to enhance a domain that, while non-narrative, is ultimately charged with tensions that seem lived—like life on the ground.

Clearly, my observations, which give way to interpretations, are quite subjective, and thus are subject to challenges from other viewers. Does this sense of apparent “openness” get us closer to any conclusions regarding the how of looking at paintings?

I want to suggest that looking at abstract paintings—which relies on imaginative decoding—can work alongside Koffka’s notion of the whole being other to the sum of its parts, and can help us understand, finally, how painting exhibitions work. At the outset of the experience, looking at a show of wonderful abstractions such as Neudorf’s offers a shared, communal opportunity. Any of us can stop to encounter the show of colourful canvases in the white gallery and attempt to engage the energy there (whether exuberant or muted). But soon enough, when we move closer to the works, we enter an intimate experience. We meet the works alone (or perhaps with a friend), and the earlier, shared entrée gives way to experience that is particular, momentary and strange. It is perhaps like going to a party that at first seems a wild melee, but where, some time later that evening, one may meet a poet and be quietly changed upon hearing a few of her words. ❚

“roll and rot” was exhibited at DNA Artspace, London, ON, from May 26 to June 30, 2017.

Patrick Mahon is an artist, curator and teacher in London, ON, who likes to think about, and write about, painting.