Kevin Kelly

Over the past 15 years or so, painting has managed to reestablish its place in the world of contemporary art, to regain some of its stature in critical circles and consolidate its value in the art market. If it has been all downhill for painting from about 1960 onward, since 2000 painters in diverse locations around the globe have been applying to the old medium lessons learned from the neo avant-garde. Painting’s questions are now inseparable from the questions of minimalism, performance, conceptualism, institutional critique, photography, gender, spatial geography, politics and so on. This is true in the largest cosmopolitan centres like London and New York, where painting never really lost its market appeal in the first place, and it seems true in Winnipeg, where a strong painting culture seems to have endured the long winter the medium has experienced elsewhere.

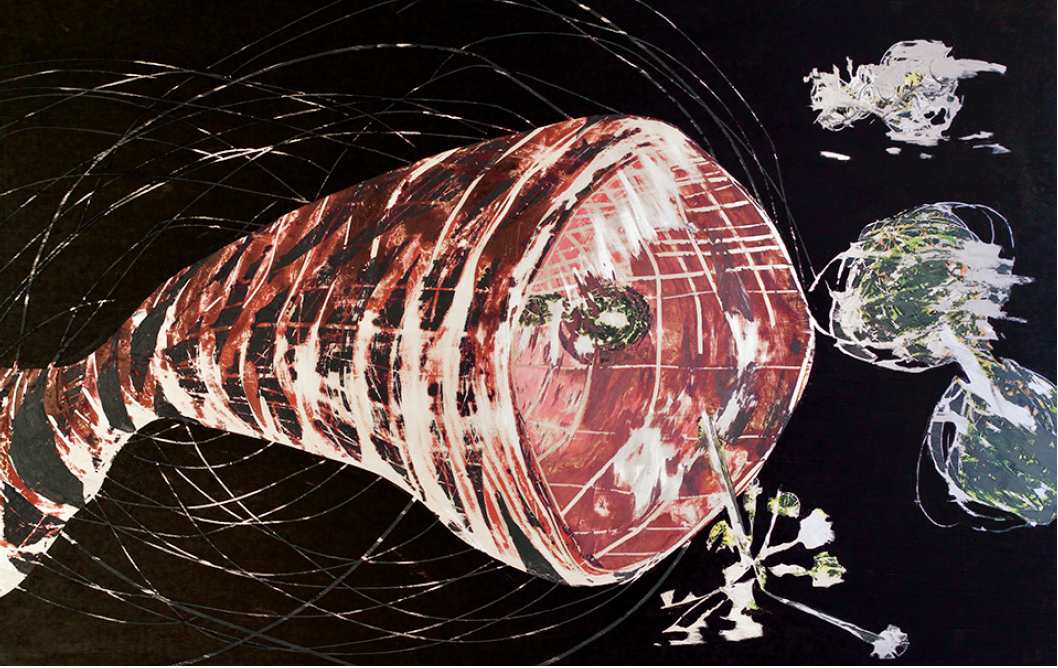

Kevin Kelly, Station Catagalo and Its Moon, 2016, acrylic paint on aluminum, 3 x 6 feet. All images courtesy the artist and Lantern, Winnipeg.

Kevin Kelly’s new paintings, at Lantern Gallery, fit somewhere into this very rough, broad context. Referred to as “Space Stations” by the artist, the works consist of two basic components: first, an expressionist language of the artist’s own making that is applied to the surface as paint; and second, a variety of very contemporary looking aluminum supports that appear to have been made by fabricators. I break down Kelly’s work into two parts because in looking at the exhibition, I was constantly torn between the painting and the painterly object. In truth, I felt the supports themselves were so intriguing and compelling that the painterly subject matter on the surface began to seem irrelevant. Thus, the reference to the spatial politics of Rio de Janeiro on a didactic panel in the gallery was for me, entirely anecdotal. Kelly’s series gives the sense that the polished support is intended to be the vehicle for a kind of space travel forwarded by the subject matter, which is often abstract or slightly sci-fi. But this happy marriage between form and content is oddly unbalanced. Time and time again I found myself tripping up on the tension between support and surface to the extent that the disconnection between painting and painterly object seemed to be the crux. Thus, my preference for Wormhole, an aluminum support without paint, marked instead with the glistening scratches of grinding or sanding. In this work painting doesn’t get in the way of the support. I also had the desire to scratch or peel a little of the black paint off Station Catagalo and Its Moon. I felt the paint was not only thin, but that in some way it may not have properly bonded with the surface and hence might be removed—a question that comes up in some of Robert Ryman’s recent white paintings done on stainless steel, and also in the spray paintings of Jules Olitski, where paint merely covers a surface rather than soaking into it.

Black Hole Red Hole, 2016, oil paint on aluminum, 3 x 6 feet.

But there is more. There is a certain functionalism to these works that demands a behavioural response. Here, I refer to the legacy of minimalism, which is built into the support, and therefore has a very strong presence, relative to the surface. The works call up the cantilevered and projecting, wallmounted objects of Donald Judd, and also the works of Imi Knoebel. In both Knoebel and Kelly’s work I am always attracted to the metal strapping or armature making up the support, which can only be seen from the side. The fact that each of Kelly’s paintings is constructed differently demands attention; one more reason why I believe the frontal view, which we associate with the optic of painting, is from this artist’s perspective, if not on its last legs, then at least overly restrictive. Something similar is confirmed by the citational network of Wormhole. After a while it dawned on me that the language of Expressionism wrought in brushed aluminum was a gesture to David Smith’s “Cubi” series. In these works the American sculptor would have us look from all sides, but would also have us acknowledge the painterly convention of frontality as a special function of the fetish. On this point in particular, the history of painting that gives a special place to Jackson Pollock emerges as part of a sexual politics, where frontality comes into focus as a masculine discourse that must be deconstructed. For Kelly, who grew up in that other Modernist bastion of Prairie culture known as Edmonton, front-facingness is always a question, part of a painterly discourse of heteronormativity. In this sense, Kelly’s work instrumentalizes certain historical techniques of viewing, puts them under pressure, and uses them for leverage to speak about contemporary issues. ❚

“New Space Stations: Rio de Janeiro” was exhibited at Lantern Gallery, Winnipeg, from December 2, 2016 to January 6, 2017.

Shep Steiner is Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art and Theory at the School of Art, University of Manitoba.