Kelly Richardson

It’s easy to think about Kelly Richardson’s work in terms of science-fiction and cinematic tropes and it’s this access that accounts for her works’ popular appeal; a certain critical understanding comes from recognizing and reflecting on Hollywood artifice. Her works do contain those possibilities, and I’m not going to deny them, but also suggest that to read Richardson’s efforts only as serious admonitions, using a fictional future to tell us about dire present conditions, is to miss out on her sophisticated humour. The recent exhibition “Kelly Richardson: Legion” includes large-and small-scale works and it might be tempting, given the obvious production values and cinematic presences of the large installations, to disregard the smaller and shorter pieces as “sketches,” “juvenilia” or “experiments.” It doesn’t help that in the Albright-Knox installation, three shorter works were separated considerably from the rest of the exhibition. Still, the single-channel pieces are important attitudinal keys and the focus of this alternative reading, since they give us permission not to take the dysfunctional machines and floating fireballs so seriously.

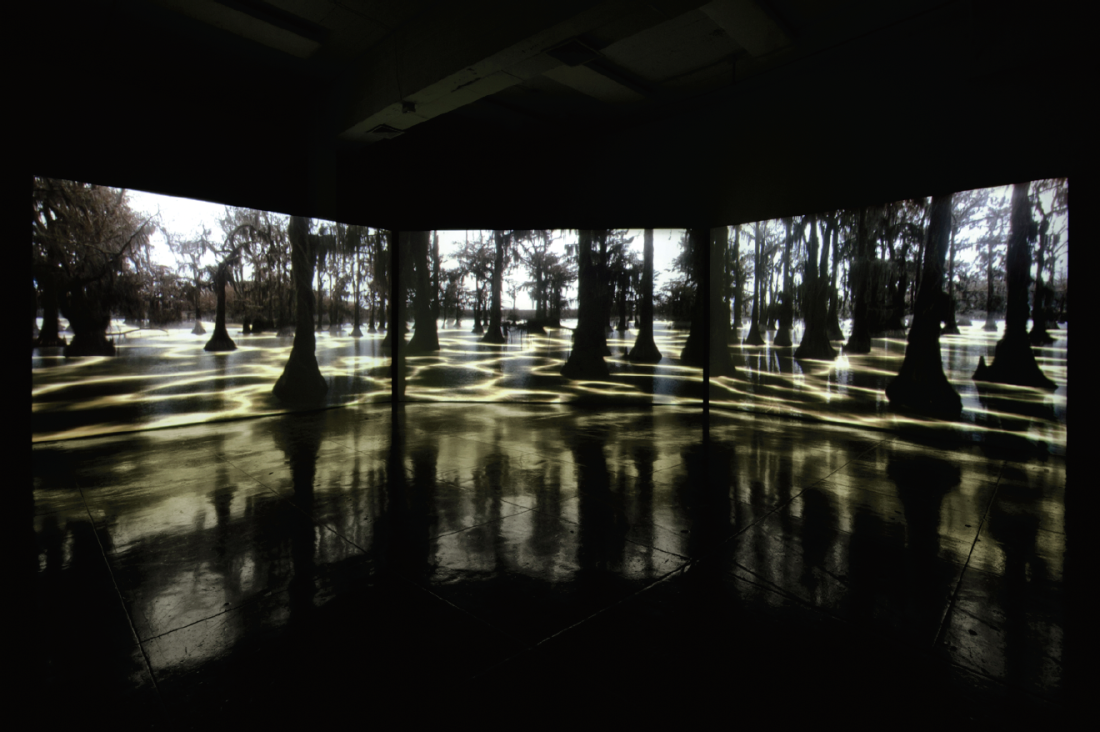

Kelly Richardson, Leviathan, 2011, installation view, 3 screen HD video installation with audio, 2011. Image courtesy the artist and Birch Libralato. Photograph: Kelly Richardson.

The long tracking shot of Ferman Drive, 2003–05, pays off in a punchline in which Richardson renders the suburban house of her childhood spinning like a top among suburban banality—she even adds as a wink at the end, the glint of a passing car’s headlight. In many ways the inclusion of this piece acts as a foil to her other videos that refuse narrative resolution. With jokiness that reaches back into video art history, Ferman Drive seems far more conventional than works in which viewers are held in a state of expectancy, but this video shows that Richardson is not as humourless as so many critical interpretations of her work about apocalyptic environmental destruction might suggest. Camp, 1998, in all of the ambiguity and irony this title suggests, also shows Richardson’s impishness, especially as the cycled popping corn soundtrack works itself into orgasmic denouement every two minutes.

The Sequel, 2004, has a Warholian stupidity and brilliance—as we witness a tire spring to life we sustain a metaphysical smackdown. The naturalistic recording of grasses in the breeze is run backwards, and we give so much credence to the medium that we can’t see the awkward movements in front of us.

Richardson arrived at her idiomatic suspension of time in earlier works, whether you consider the existential absurdity of the auto endlessly waiting by a stop sign in the barren desertscape of A Car Stopped…, 2001, or the quotidian sedan achieving extraordinary hang time in Wagons Roll (The Remake), 2003–07. Far from being video stills, in these works clouds roll, birds fly by and wheels spin to give motion, but withhold narrative. Another title speaks to these otherwise still situations: There’s a Lot There, 2001, is a two-minute loop of a tree-framed sunset over a lake. Subtle camera shake and old-school National Television Standards Comittee scan lines grating against a screen door’s grid activate a moiré effect in which the quotidian becomes dazzling, a gorgeous optical flicker of shifting colours in the half-light. The mosquitoes are amusing interventions, especially as Richardson heightens their presence though shrill electronic audio that makes them at once seem threatening, comic and fake.

Kelly Richardson, Mariner 9, 2012, installation view, 3 channel HD video installation with 5.1 audio. Image courtesy the artist and Birch Libralato. Photograph: Colin Davison.

Turning to the large installations, there’s great humour in Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006—the title itself seems like a lesser Orson Scott Card novel—but the main computer-generated image feature is really quite funny. For some, the fire raining on the landscape is right out of St. John’s End of Days. But there is no terror without destruction. Rather than punctuating the equilibrium of the ideal lake-and-mountains sunrise, the flames are no more threatening than blazing amaretti wrappers landing with gentle audio splashes. Despite a didactic text that asks us to think about failing infrastructures and future environmental disaster, it’s far more parsimonious to think about what’s in front of us. The Erudition, 2010, for instance, might best be understood as a video about video. The landscape spread across three screens is discontinuous, has intense colouration and irrational, split light sources. Marking transitional and dream states, Richardson uses a poignant half-light in most works. Adding more artistry to the artifice, she zaps in out-of-scale, white-blue, translucent conifers. Their glitchy bending in an unseen wind seems an homage to American video and media artist Jennifer Steinkamp, who often lends anthropomorphic movements to her verdant imagery. Richardson’s virtual is now, the mediation is the message and doesn’t require the distancing of a sci-fi rationale.

With its panoramic scale and impressive hand-rendered CGI, the show’s desolate centrepiece, Mariner 9, 2012, teeters on ponderousness. Thankfully, it contains enough absurdity to subvert elegiac reception. We have to laugh at ourselves if we find pathos in the ridiculous robots repetitively scratching soil, spinning wheels or waving rocks. It’s tempting to overstate that the machines are symbols of our hubris and markers of marooned human ambition, but it seems more apt to think of them as Duchamp’s sad, impotent bachelors. ❚

“Kelly Richardson: Legion” is being exhibited at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York from February 16 to June 9, 2013.

William V Ganis is a professor of art history and gallery director at Wells College, New York.