Kees van Dongen

The pensive head of a nude woman in the upper right quadrant looms from the darkness like a weary succubus. Her eyes seem haunted, her pursed lips full. One arm is draped languidly over the side of the chair in which she sits as she turns towards us. She peers out at the painter, and at us, holding us inside an intimate space rather than an outer darkness marked by the century since her coming into being. An aura of truth is presented in this optic embrace, and we recognize that her sad eyes look inwards, not outwards, that their truth is one of pure interiority.

Nude in an Armchair was painted in 1896 when Kees van Dongen was barely 19 years old. In this one painting, we are given a fully adult dose of his genius—and the full measure of his promise. It is only one among a number of portraits by the Dutch Fauve painter that held the viewer taut, somewhere between rapt attention and rapture in the first major retrospective of his art in North America. Jointly organized by the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts and the Nouveau Musée national de Monaco, the exhibition was replete with such seldom-seen and serenely enticing masterworks.

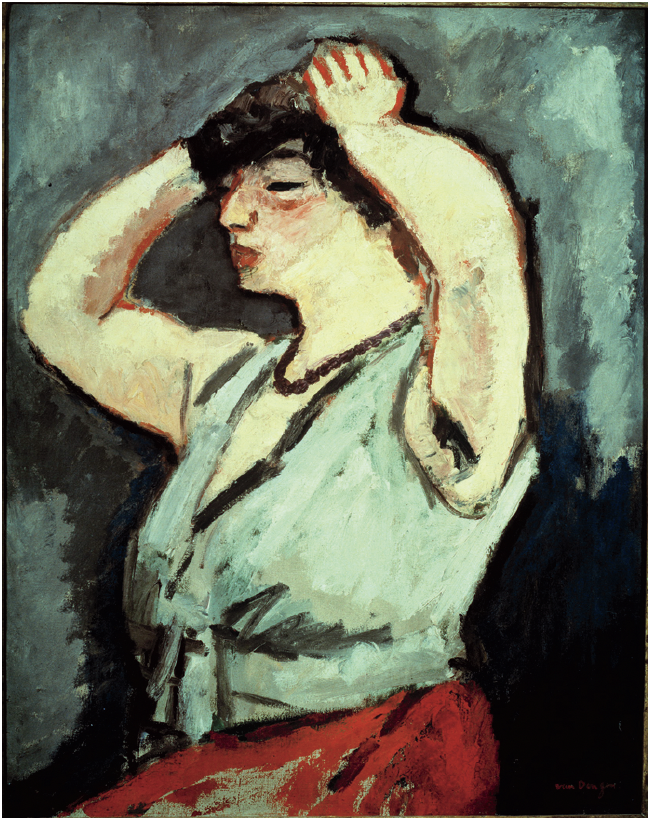

Kees van Dongen, The Manila Shawl, about 1907–09, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. Private collection, S & P Traboulsi. © Estate of Kees van Dongen/SODRAC (2008). Courtesy Montréal Museum of Fine Arts.

Van Dongen is better known for work undertaken much later in Paris where his Fauvist canvases were once all the rage, but I hold that this single painting is worth the price of admission to the painter’s eloquent and sultry universe, rife as it is with shadowy revelations and epiphanies like the chromatic clusters of reds, yellows, oranges and adumbrated blacks that move restlessly across the vast array of shawls, throws, rugs and gowns that so effortlessly hold and seduce the eye.

Perhaps the most startling revelation of the exhibition is the inordinate strength of the early work. Tasting such a rich sampling of the first two decades of van Dongen’s work makes for a hedonist’s field day and allows us to come to terms with an artist of precocious, prodigious gifts— intent upon experimentalism and the organic development of a remarkably sensuous palette. With well over 200 works, including over 100 paintings, as well as dozens of drawings, prints and sundry archival documents (including period photographs), and even some marvelous Fauvist ceramics, this exhibition marked a curatorial high point for the museum and the season.

Van Dongen has been called both moralist and misogynist. How much of a moralist? The moral of his story certainly is latent in his attraction to and desire to paint the marginalized, the underclass. He was drawn there and, at least in the early work, was seldom a creature of censure. Was the work misogynistic? Not much, I’d say. Did he hate or even disdain his subjects or was his mien purely clinical? Lucian Freud, morgue-master, has also been called a misogynist, and perhaps with more justification. Instead, van Dongen’s work brims with sympathy, even when his brush is at its most caustic— and cathartic. He never quite lost his early anarchistic leanings, his love of the fringe, his hunger for the downside and the Outside. Those early tendencies may have gone underground somewhat over the years—but, in the end, their still-vestigial presence made him a better painter.

Kees van Dongen, Fernande Olivier or The Spanish Woman or Bust of a Woman, about 1906–07, oil on canvas, 91 x 72 cm. Private collection, S & P Traboulsi. © Estate of Kees van Dongen/SODRAC (2008). Courtesy Montréal Museum of Fine Arts.

Van Dongen was the quintessential observer, and his brush was his instrument, emerging opportunistically from a privileged perspective to record with virtuosity and observational acuity the full range of the social, from the depths of Bohemia to the airy upper registers of the demimondaines of a so-called Cocktail Age fraught with flappers and gin fizzes. His brush is a barometer, too, maybe, gauging the relative humidity of the social world. The distended atmosphere rules here, the mercury rises, and the palette becomes almost white-hot at times, in riotous fantasias. It is no exaggeration to suggest that his level of observation was almost opthamalogically precise, as though he were a gifted eye surgeon of the social, particularly in the later society portraits.

Salutary high notes of the exhibition included the outstanding collection of works by van Dongen acquired not long ago by the Nouveau Musée national de Monaco, including The Wrestlers or Tabarin Wrestlers, 1907–1908, a remarkable work that has not been publicly exhibited for over 50 years. Any critic has his or her own pick hits, and mine included Interior with Yellow Door, 1911, with its vertical Rothko-esque yellow block of pure chroma, The Manila Shawl, circa 1910–11, the shawl of the title festooned with those lovely chromatic clusters mentioned earlier, Jack Johnson, 1919, with its Le Douanier Rousseau-like resonance, Joaquina, 1911–12 of the haunting beauty and the lithe angularity of the nude dancing with an angel in Tango of the Archangel, 1922–1935. As the viewer followed the trajectory of the artist’s career from Rotterdam to Paris, and back again, before settling in Paris in 1899 and onwards, it became evident just how sublime a talent his was. He was the only sustained portraitist among the Fauves, and van Dongen’s reputation is poised to soar once again in the wake of this exhibition, which shows that, in many ways, he was an equal to his contemporaries Picasso and Matisse. ❚

“Van Dongen: Painting the Town Fauve,” curated by Nathalie Bondil and Jean-Michel Bouhours, was exhibited at the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts from January 22 to April 19, 2009.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montréal who contributes regularly to Border Crossings.