Karen Jordan and Norman Takeuchi

For 18 years, Ottawa artist Karen Jordon has been collecting her own hair to create sculptures. After washing, she rakes it gently with her hands, which leaves her with a handful of shed curls. In a continuing project that has come to measure the passing of her life, she wraps these curls with a cotton thread to create small, twisted shapes she calls Cultivars.

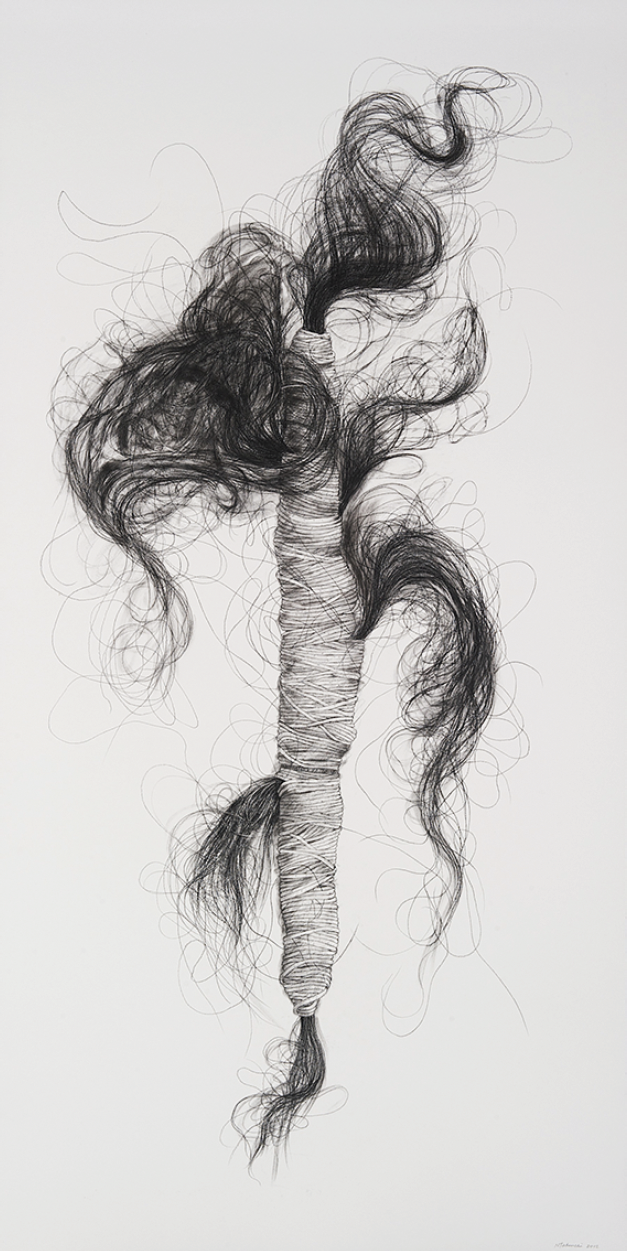

Norman Takeuchi, Cultivar No. 5, 2012, Conté on paper, 182.9 x 92.2 cm, collection of the artist. Photograph: David Barbour

Having seen an exhibition of Cultivars, Norman Takeuchi, who is an Ottawa painter with exquisite drawing skills, was so impressed with the graphic quality and the organic lines of the work, that he asked Jordon if he could borrow a few to draw. The results were seen in the recent exhibition “Hair Lines,” at the Mississippi Valley Textile Museum in Almonte (a small town near Ottawa): Takeuchi’s Conté and graphite drawings of various dimensions are coupled with groups and lines of Jordon’s sculptures, of which there are now about 400. The post-industrial setting of this exhibition, a former wool mill turned museum, becomes the third player in this collaboration. The peeling plaster and paint on the stone walls form a testament to the struggle between human intent and natural decay; they add their own lines to the striking visual discussion on nature and culture that the artists initiate.

The beauty of the marks that emerge from the painstaking craftsmanship of both artists lures the viewer into a meditative contemplation of the lines’ infinite variations. In medieval times, tracing embellishing curvilinear patterns in illuminated manuscripts was a meditative exercise, thought to lead to greater understanding of divine order, but the viewer of “Hair Lines” is more likely to garner earthly insights. Rather than forming recognizable patterns or symbols, the wild, irregular loops and curls of the sculptures and drawings lead nowhere specific.

Human hair, the natural source of the artworks, differs from other body parts in that it is shed and regrown. A “crop” of hair can be cultivated, grown long or cut short, a notion Jordon plays with in her title. Only nails share this bodily characteristic, and both nails and hair can look remarkably alive for some time after death. Despite this durability, hair is more transient than most of the rest of the human body; perhaps this explains our disgust at seeing hairs and nails no longer attached to the body. Hairs in the wrong places are considered abject, a sign of natural decay, a decay that much of our cultural efforts are bent to stave off.

Karen Jordon, Cultivars, (Series 2/435) 1994–, hair, cotton string, straight pins, average size 34.5 x 2.3 cm, collection of the artist. Photograph: Lawrence Cook

The will to master nature remains evident in Jordon’s wrapping of shed curls but, paradoxically, the irrational obsessiveness of her project demonstrates the futility of the effort. Jordon’s latest Cultivars are here pleated rather than wrapped with string. This is partly due to the arthritis that began to bother the artist’s wrist after years of wrapping; the organic protest by her own body appears to have allowed nature more slack.

While Jordon’s Cultivars play with divisions of culture and nature and reflect a human anxiety about the change and decay that comes with being part of nature, Takeuchi’s drawings ostensibly pull the sculptures into a static, cultural domain. His traditional way of representation freezes them in set positions, as if shielding the creatures from nature’s contingencies. Yet the drawings remain emphatically sympathetic to their subjects, and render them with the utmost attention to the fluidity and multiplicity of their lines. In addition, a gradual freeing of movement over time appears in Takeuchi’s drawings. Initially, he created small ones; some are shown here framed behind glass, looking much like natural history drawings. Medium-sized works show enlarged, expressive details of the sculptures. Unframed, but still pinned to the wall, they are a step closer to the looseness of the large, six-foot-tall, free-hanging drawings. Here, what Takeuchi draws out of Jordon’s creations and magnifies for emphasis is neither human, animal nor plant-like, but a raw vital force common to all life on earth: a force that works as much with the bindings as against it.

Jordon’s obsessiveness is matched by Takeuchi’s more decisive but contradictory positions. Together with the patterns and lines of the gallery’s stone wall, “Hair Lines” makes a mockery of any attempt to draw lines between nature and culture. ❚

“Karen Jordon and Norman Takeuchi: Hair Lines” was exhibited at the Mississippi Valley Textile Museum, Almonte, Ontario, from November 17, 2012 to January 12, 2013.

Petra Halkes is an artist, writer and curator in Ottawa and a regular contributor to Border Crossings.