Karel Funk

First of all I would like to say, go and see Karel Funk’s retrospective at the Winnipeg Art Gallery if you can. It is an experience that can send you through a surprising number of loops considering the narrowness of its formal approach. Many of the things that people say about Funk’s work are true: they are consummately painted, super-realist images, fraught with a certain anxiety and self-consciousness that is based both on formal choices and subject; see them for yourself and read the insightful WAG catalogue. What I am interested in asking is something that might be a flawed question but one that nags at me: what if the work, for all its polish and presence, doesn’t really want to be looked at? Or, put another way, what if these paintings warn against wasting one’s precious time looking at pictures? This introduces a moralizing tone, and perhaps also an absurdist one. These ideas aren’t usually attached to Funk’s practice and I am fairly certain are quite the opposite of his intentions. But bear with me while I untie this knotted logic.

Karel Funk, Untitled #65, 2014, acrylic on panel, 76.2 x 91.4 cm. Collection Majudia. All images © Karel Funk. All images courtesy 303 Gallery, New York, and Galerie Division, Montreal.

A great thing about the WAG show is that you can see 14 years of Funk’s work and how it slowly works its way forward, sorting out painterly issues, all the while filing itself down to an even steelier, more acute point. The imagery has become more and more reductive—pictures of people (averting their gaze or from behind) or what we assume are people in hi-tech outerwear, or even just the outerwear itself. I believe Funk’s work to be more than some kind of anti-portraiture, more than just images enacting an anonymous, voyeuristic intimacy, more than just surface; but these ingredients are clearly integral to what these images may truly add up to. If we propose that Funk works within the tradition of Vanitas painting instead of portraiture, we can delve deeper into subject rather than surface.

What set me on this inquiring path were two paintings in this exhibition, one from 2013 and the other from a year later. Both depict plastic objects upon the usual slightly cool white background shared with the portraits. They reveal the ultimate concerns barely alluded to but present in all the other works: death and plastic. The still lifes may not be as ambiguous as the other works. I am not certain what to do with Funk’s portraits other than look at the fineness of the mechanics of painting them, since I am also a painter and can easily succumb to that kind of nerdy, close-study behaviour. But seeing the still lifes triggered something else; I began to see all his subjects as being contained in plastic. Plastic never dies, but the things inside their shells will.

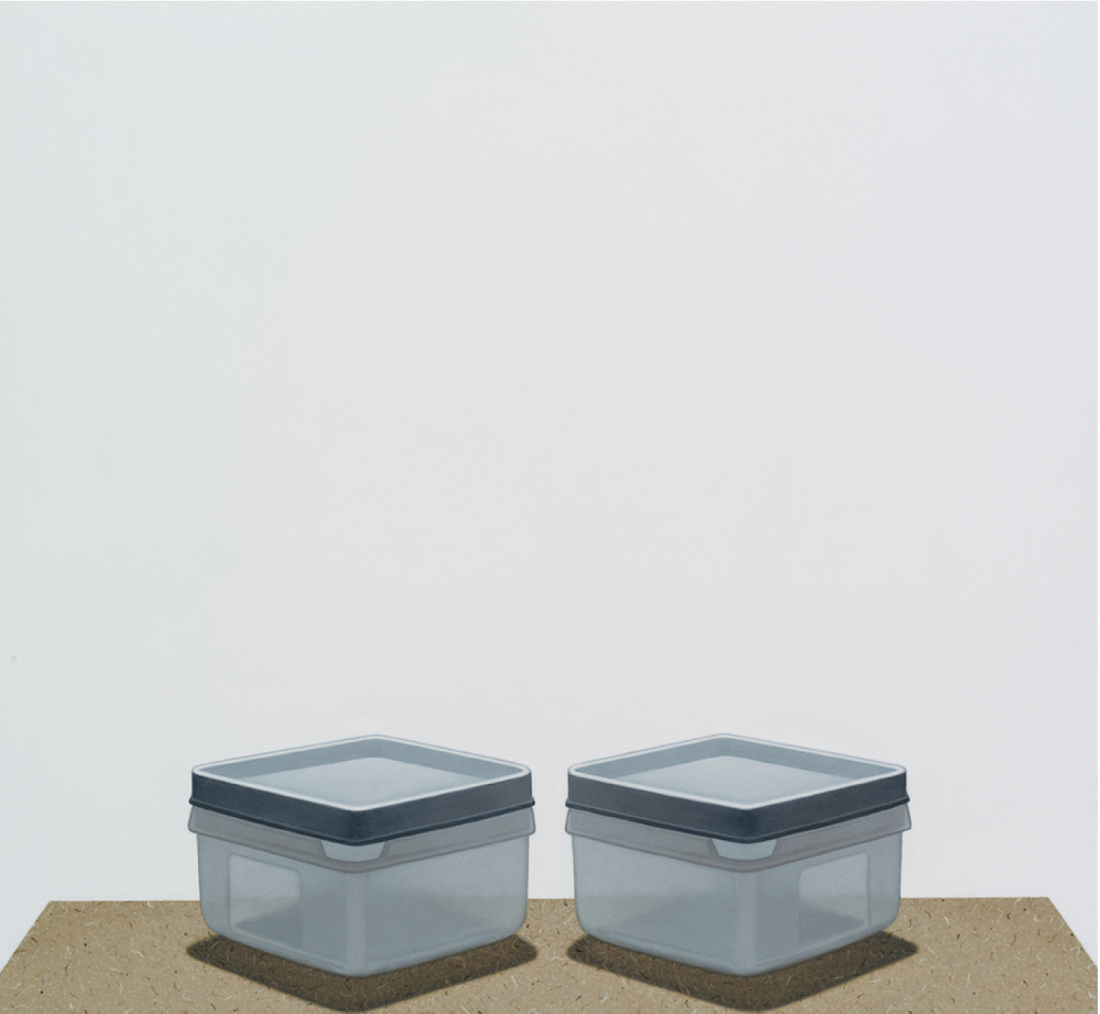

Untitled #66, 2014, acrylic on panel, 91.4 x 76.2 cm. Collection of Jennifer Blumenthal and Daniel Bubis.

The still lifes directly reference Vanitas paintings, so this move towards narrative is not just my imagination; it is concretely there. The question is, should we retroactively apply it as a lens upon the other works in the exhibition? It may be important to introduce a couple of Wikipedia definitions: 1) Vanitas relates specifically to the tradition of Netherlandish still life painting of the 16th and 17th centuries that Funk acknowledges as an influence on his latest paintings; the interpretation of the Latin root oscillates between ‘emptiness’ and ‘futility’…basically all is Vanity, and you can’t take it with you when you die. 2) Memento Mori, “Remember that you have to die,” has its roots with the Romans. During a victorious general’s triumphed parade, a slave was required to follow the great man and intone in his ear, “Respice post te. Hominem te memento” / “Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you’re [only] a man” lest his ego get too large and cloud his noble mind with pride. Check yourself before you wreck yourself, if you will. The concept of Memento Mori was also an important part of ascetic disciplines used as a means to perfect one’s character by cultivating detachment.

When these possible symbologies are highlighted in Funk’s work the paintings are at home within their proper tradition. But, does this alternate reading set the work up as a moral trap? One irony is that art must be looked at, but Funk’s work warns you not to look too long. You are burning daylight, Death is waiting…and in order for this message to be transmitted, plenty of time transpires during both the making and deciphering of these oftentimes-oblique images. The more time you spend looking at these translations of reality the longer they have to work their wiles upon you. Thus we have a kind of postmodern conundrum where traditional Vanitas painting collides with the rhetoric of Memento Mori in the ever more demanding analogue medium that is painting; poor painting left to stand holding out its solemn old message.

Untitled #61, 2014, acrylic on panel, 47 x 50.8 cm. Claridge Collection, Montreal.

Untitled #61 depicts two clear sandwich containers, objects designed to hold and protect food from exposure and decay; in fact the containers are what Funk uses to store his pre-mixed paints, before they dry up and die. The other painting, Untitled #58, depicts three plastic kitsch objects: a cactus, a skull and a children’s toy thermometer. Read these as you will, but there are two things we can be sure of in this world, Death and Plastic and we shall be taxed on them both. Look but don’t linger, unless you desire the chance to laugh in Death’s face. ❚

Karel Funk is on exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery from June 11 to October 2, 2016.

Craig Love is a Winnipeg-based painter who occasionally writes about art.