Kai Althoff

The 40-something German artist Kai Althoff’s first exhibition in Canada at the Vancouver Art Gallery was timed to coincide with another solo show, one floor below in the gallery, of works by the local photoconceptualist Jeff Wall. At first blush, the two artists seem to have little in common; yet it was Wall who recommended Althoff to the VAG as a good pairing with his own work, and by strange contrast, he’s right. It’s an inspired decision. The artists share themes, each struggles to enact scenarios that deal with ideas of power and liberty, and they even overlap in influences, perhaps through a shared interest in Krautrock music. Althoff and Wall have both done time with experimental noise—rock bands. For Althoff it’s the group Workshop, for Wall, it was UJ3RK5. But in Wall’s art, every ambiguity is in a state of constant focus and the borders are well-defined; in Althoff’s, the details are bright but blurred and there are no restrictions to the approach. Althoff work was given three separate spaces on the top floor of the VAG to work with, and in them, he presented three separate but connected ideas of art. After ascending the escalator to discover a roomful of splendid steel, ceramic and collage-based sculptural works, the viewer moves to the central atelier where a “weaving station” has been constructed, encouraging participation by learning the age-old craft of the handloom; or you can watch a video documenting i will be last, a theatre piece that Althoff performed with a few others that expressed, mainly through improvised dance, the irrationality of violence. The final third of the exhibition is dedicated to a retrospective, in miniature, of Althoff’s various narrative series of paintings and drawings, thirty works culled from various bodies that date back to the early ’90s and include examples of solo shows at commercial galleries, like Anton Kern in New York and ACME in Los Angeles, alongside decent juvenilia and startling one-offs. This wildly diverse art career was already described in 2002 by critic Tom Holert as “an ongoing process of negating stylistic coherence.” For a show with such a varied, possibly incoherent output, it’s in the room of his paintings that we see the clearest indications of Althoff’s growing maturity as an artist, not only in his proficiency with composition and materials but also in the progressive depth of his ideas.

Kai Althoff, Uwe: Auf gitem Rat folgt Missetat (Uwe: from good advice to vice), 1994, crayon, pencil, water-based paint on paper. Collection of Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller, Cologne. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Stylistic incoherence doesn’t necessarily mean thematic problems. Althoff is, like Wall, also highly focused on evaluations of history, and his artwork often provides a succinct critique of authority. In his paintings as well as his sculpture and collaborative efforts, Althoff’s themes study the dehumanizing effects of war and the dissolution through poverty of human dignity. To counter these grim truths, he offers the humanizing potency of collaboration. His drawings and paintings feature soldiers abusing each other, adolescents preying on each other, possessive fathers, drunken wastrels, whores and perverts, and in all, he draws a great deal of his strength by following the age-old dictate to “speak truth to power.” His angular drawing style is a combination of kiddie comic and black humour, with the selftaught beauty of Schiele and some of the intellectual brutality of Otto Dix. Althoff’s earliest drawings remind me of the pointillist handling of the far-outsider Maxon Crumb in San Francisco who also uses tiny bacterial dots to shade in the ribcages and neck tendons of elongated ectomorphic half-humanoid creatures. The first sculpture you see as you enter the exhibit is made from iron rebar bent and shaped to portray the figure of a pleasedlooking woman with her head bent all the way under her own crinoline. Only the crinoline is fabricated in three dimensions, the rest of the sculpture is in profile, as flat as a wrought-iron fence. She could be outside a Rococo burlesque club from the 19th century or envisioned as a twist on the style of the Weimar Republic for a cabaret garden. Her gloved hands are stretched up high above her, and each wrist is decorated with a large rebar pompom. She’s wearing chunky high-heeled boots underneath the crinoline. Maybe she’s the artist’s tribute to the cancan dancers and carnival life of yesteryear—whatever the inspiration, a sense of nostalgia for the way things never were pervades this work and the one next to it—a green lion in an orange cage. His sculptures seemed designed to inhabit someplace in the mind that combines the sweet fantasias of a children’s pavilion and a bawdy house, an uncensored journey into the looking glass. The two ironworks share Althoff’s singular style of representation, too. The orange ironwork cage that traps the green ceramic lion is made of a pattern of marching policemen. Each guard swings his key on one finger. It’s the repetition of the guard circling the lion that creates the prison. Designed with the same sharp profile as the lady with her head between her knees, the warden and the lady remind me of characters from drawings by Julie Morstad or Amy Cutler, artists who share Althoff’s interest in children’s book illustration and dream imagery. The front room also houses three large vitrines draped in red mylar, giving everything behind the glass a rosy tint. The contents of each vitrine is collected from the results of a monthlong residency that Althoff and another artist, Lutz Braun, took up in an abandoned office space near a Berlin art fair in 2006. Under the title Kolten Flynn, the two artists spent each day at the office making art.

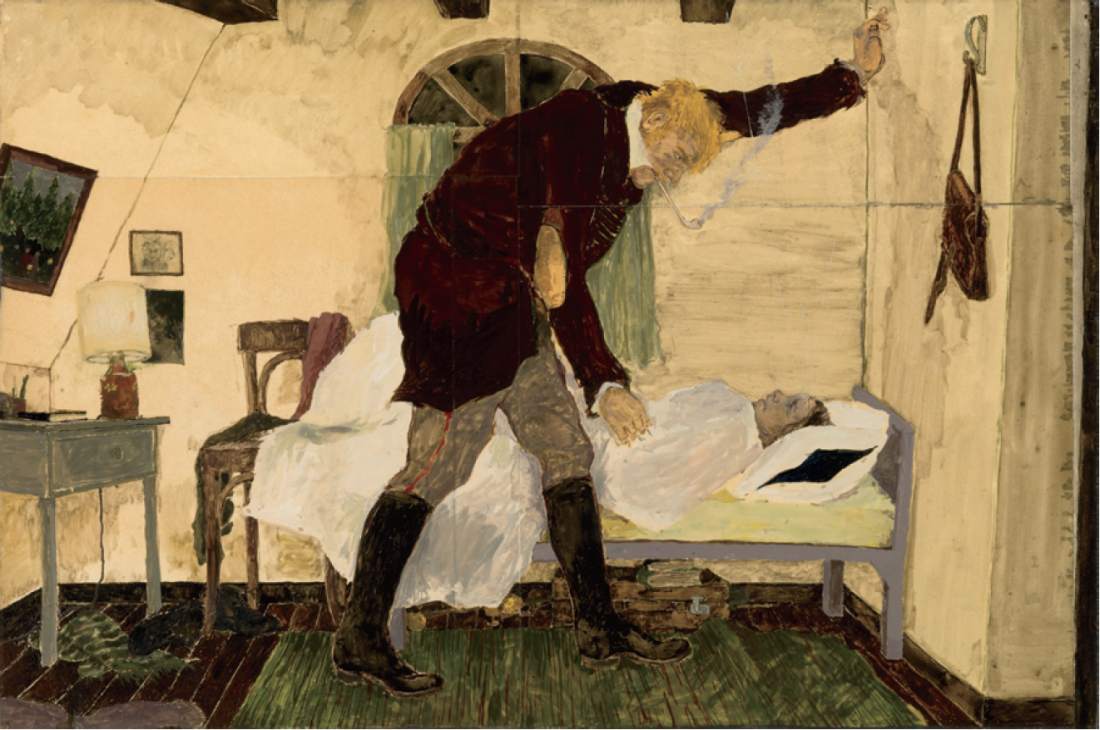

Kai Althoff, Untitled (from Impulse; scene in room with bed), 2001, lacquer, paper, watercolour, varnish. Private collection. Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Much like the spirit that guides Paul Butler’s Collage Party, the two artists conceived of no particular goal or outcome for the month, except to make stuff, a lot of stuff. So inside these vitrines you find small sketches ranging from the pornographic to ordinary portraits, ballpoint love letters, quasi-religious masks and figurines, Balinese paper puppets, occult symbols, totemic assemblages of found objects and obscure magazine cutouts. Finally, there is the centre room where the weaving stations are set up, and these complete the VAG’s only too-brief picture of Althoff’s openended art practice. Between the poles of his own two hands, sculpture and painting, Althoff chose to include an interactive craft centre, The Weaving Place. Here, gallery visitors sit for a session at a portable handheld loom, learning how to turn wool into fabric. The Laser-Loom was invented by San Francisco artist Travis Joseph Meinolf whom Althoff met while in California. In effect, Althoff has used a third of his space in the gallery to showcase another artist’s work, to celebrate an artist whose own ideas then offer up the room to the viewer to participate. This is only an example of how far Althoff wants to stretch his art practice away from his own touch, to find his themes in the activities of others like a curator does, or perhaps he’s looking for another path to find his voice against the will of authority. Global authority, curatorial authority, himself. The world never seems to lack for doctrines to liberate. ❚

“Kai Althoff” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from November 8, 2008, to February 15, 2009.

Lee Henderson is the author of a book of short stories, The Broken Record Technique. His first novel, The Man Game, was published by Penguin Canada in August 2008. He is a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.