Josef Sudek

The photographer Josef Sudek lived through extraordinarily tumultuous times and suffered a tremendous physical wound that utterly changed the course of his life. This is not evident from a first glance at his work, which is serene and contemplative and mainly comprised of delicate still lifes and picturesque landscapes. A citizen of Prague his entire adult life, Sudek witnessed both world wars, and the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic and its subsequent occupation by the Nazis and then the Soviets. He lost his right arm at the age of 21, fighting for the Austro-Hungarian army in the First World War, and had to abandon his vocation as a bookbinder. Instead, he took up photography and became a fixture in the artistic life of his city, where he could regularly be seen, inseparable from his massive tripod and the large-format camera that proved best suited to his disability.

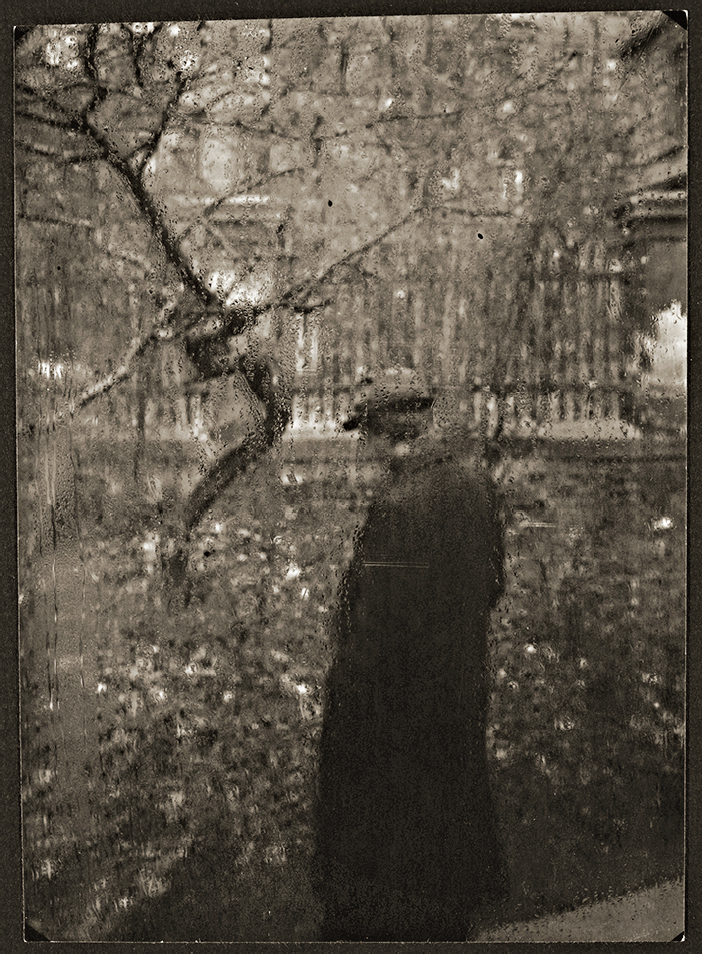

Josef Sudek, Window of My Studio, c. 1940–54, gelatin silver print, 17.1 x 12.4 cm. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: © NGC. © Estate of Josef Sudek.

The exhibition “The Intimate World of Josef Sudek” at the National Gallery of Canada offered a retrospective introduction to the entirety of the artist’s career: from his early photographs that are marked by the Romantic pictorialism that was conventional at the beginning of the 20th century, to his later, more experimental and idiosyncratic works that he produced up until his death in 1976. It is tempting to say initially that his work is mostly remarkable for what it leaves out of the frame. How imperturbable it seems when we know that its production was contemporaneous with major military conflict and social and political upheaval. The curators are at pains to draw out in didactic panels the hints of a larger, more troubling world outside linking, for example, the darkness that begins to predominate in his photographs to the onset of the Second World War and the imposition of a curfew by the occupying German forces. But if Sudek is the most important Czech photographer, it is not necessarily because of the subject matter he depicts, but more so the manner in which he does it, revealing, as the curators aver, a depth of feeling that imbues his photographs with a great sensitivity. The exhibition frames the work as a point of entry to Sudek’s private world: his intimate circle of friends and colleagues and the belongings and places that had a personal significance for him.

Although in some ways Sudek’s work could be characterized as a retreat into aesthetics, it is important to stress that a retreat is still a strategy. The exhibition was divided thematically into nine sections, and these, placed in a roughly chronological order, underscored Sudek’s individualistic pursuit of his artistic vision. An early photo (Veteran’s Home, c. 1922–1927) featuring a disabled war veteran absorbed in the contemplation of a bottle he is holding could act as a metonym for Sudek’s career, having cast himself as an outsider whose singular focus revealed worlds within worlds.

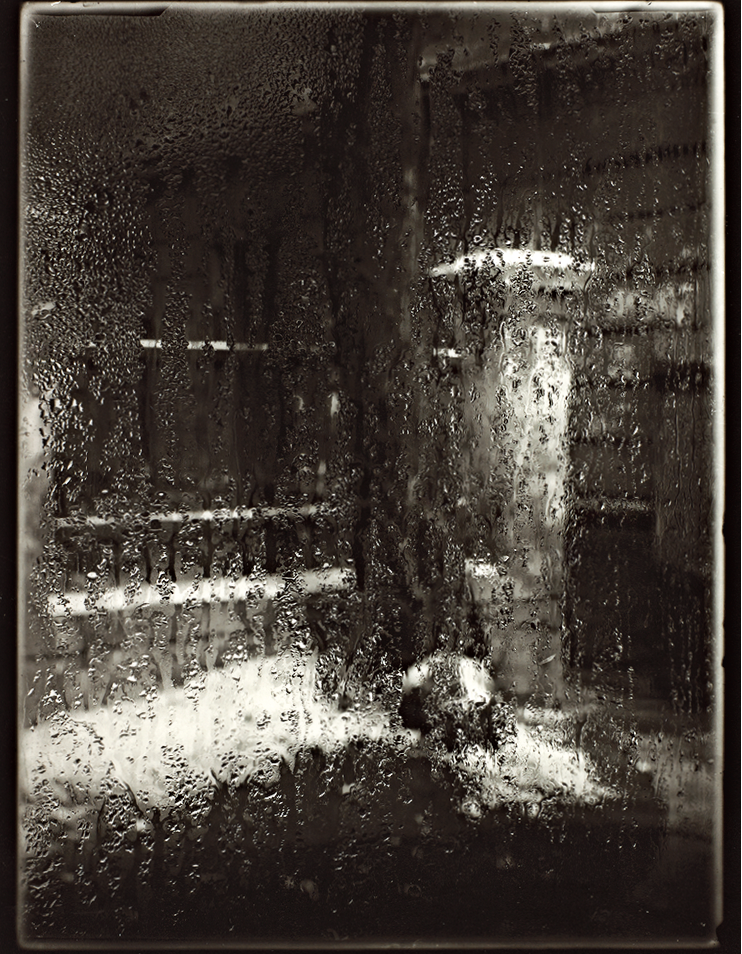

There is an incredible attention to the appearance of the material world in his photographs, which at the same time contain a constant suggestion of the impermanence or transmutability of all things. This is perhaps best manifested in his major series of photographs (“The Window of My Studio,” c. 1940–1954) that depict variable views of a crooked tree in a courtyard taken from his studio window. The images themselves contain many layers of translucency and transparency, where figures are out of focus or viewed through fogged or rain-streaked glass, giving an impression of a state somewhere between a vision and a dream. The appearance of the images is also reinforced by Sudek’s printing process and selection of material support, including various paper stocks and carbon tissues that make the photos appear as membranes between this world and another.

Four Seasons: Winter, from the series “The Window of My Studio,” c. 1940–54, gelatin silver print, 23.3 x 17.2 cm. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: © NGC. © Estate of Josef Sudek.

Sudek may have stood apart from his Czech contemporaries, but he was also at the centre of the Prague cultural milieu, as the layout of the exhibition demonstrates. The first section contains a selection of portraits of friends that Sudek took for his own use, and the last section concludes with an assortment of images by Sudek’s colleagues and apprentices, establishing that he was aware of recent trends in art even if he eschewed them. Surrealism remains, however, within his vicinity. The exhibition catalogue reveals that one of the painters whose works Sudek documented in photographs, Bedřich Vaníček, contributed to surrealist periodicals and worked on a translation of Andre Breton’s Nadja. As Walter Benjamin’s essay “Surrealism,” published in Reflections (Schocken Books, 1986) articulates, the lovers in Nadja take the everyday familiarities of “mournful railway journeys” and views through an apartment’s “rain-blurred window” and convert them into “revolutionary experience, if not action,” offering a primer for a poetic politics. Similarly, Sudek’s photographs have a charged, transformative vision.

Banal objects are romanced by his camera. In a didactic panel Sudek is quoted as saying, “I like to tell stories about the life of inanimate objects to relate something mysterious.” The impact of his work arises from a tension between the natural phenomena depicted and the artifice used to capture and compose them. Whether they are carefully constructed still lifes or landscapes that are largely comprised of manicured gardens or enclosures, these are complex images containing many elements that combine to create labyrinths charged with meaning. A hoarder, Sudek kept all kinds of dross and transmuted it into his art, even piles of sausage wrapping papers (Labyrinth on My Table, 1967). His labyrinths and magic gardens created an alternative reality. The playful and masterful combination of materials and appearances in Sudek’s work culminated in the late Puřidla, or photographs mounted on different surfaces and pressed between glass: the overall term for them is a play on words that connotes both “sandwich” and “art for art’s sake” in Czech. As Benjamin reminds us, “For art’s sake was scarcely ever to be taken literally; it was almost always a flag under which sailed a cargo that could not be declared because it still lacked a name.” The exhibition pays testament to the lasting power of Sudek’s work as a bulwark against the present that connects us to the future. ❚

“The Intimate World of Josef Sudek” was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from October 28, 2016, to February 26, 2017.

Michael Davidge is an artist, writer and independent curator who lives in Ottawa.