Jon Sasaki

Committed to the conceptualist cause, Jon Sasaki makes art that is, in part, about the process of making itself—and questioning what constitutes a creative or critical gesture. What is insightful, important or insubordinate, in art and in life? While his work suggests social situations, he refuses to offer up detailed, prescribed identities with which viewers may identify. And yet, there is an earnestness to the work, the result of a sustained devotion to causes that may seem stupid in their blankness, but still manage to deeply impress.

Sasaki’s titles often sum up the task at hand, as in the ongoing series “An Obsolete Calendar Towel Embroidered with an Identical, Future Calendar Year” (begun in 2012). Hanging on hooks and arranged as a loose grid on a single wall, these textiles feature quaint and kitschy imagery: a country clock, prizewinning vegetables, a covered bridge and phrases like “Happiness is …” As these artifacts have been converted from dish-drying devices to kitschy collection, the years to which they were once dedicated have long passed. But the embroidered gestures give them a new life, provoking subjective speculation about history repeating itself or ecologically conscious recycling. The work recalls early actions by Lawrence Weiner in which the purely textual version of the artwork—describing an action, such as Two minutes of spray paint directly upon the floor from a standard aerosol spray can, 1968—is considered just as important as the material execution. Unlike Weiner, Sasaki prioritizes the tactile presence of the skilfully stitched numbers, rendered in fluorescent colours such as green and gold.

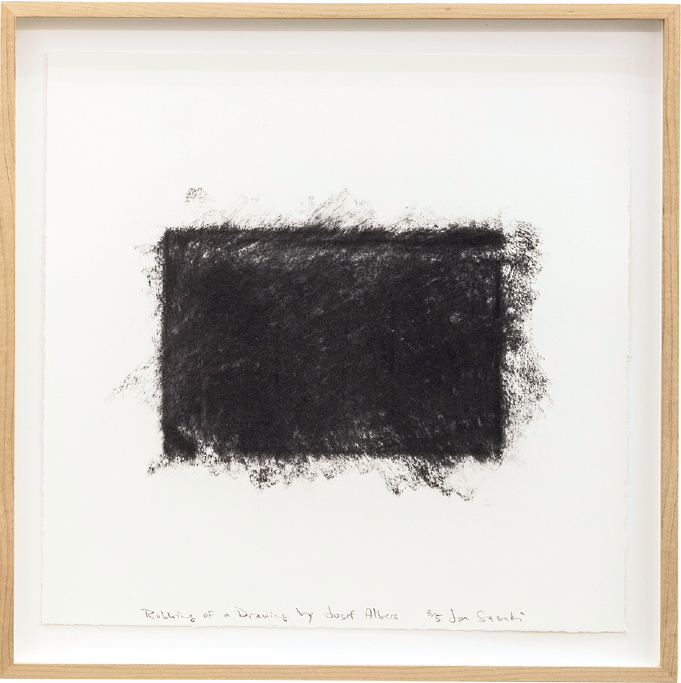

Jon Sasaki, Rubbing of a Drawing by Josef Albers, 2017, charcoal on Arnhem 1618 paper, 17 x 17 inches, framed. Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid. Images courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

Throughout the show, Sasaki performs modest and manual manipulations that seem, at turns, serious and silly, arduous and arbitrary. The series of photographs “Wishing Away The Things I Suspect Are Standing In The Way Of My Encounter With The Sublime,” 2017, reflects an ambivalent attitude toward the landscape as a spiritual outlet—or a means to channel transcendent (and/or nationalistic) forces. Travelling intrepidly to a variety of storied sites in Ontario, the artist works through disappointment. He does so, for instance, by carefully cutting out elements that distract from a timeless realm of pristine nature in Snack Bar and Gift Shop Excised from Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park. Similarly, offending bits are folded back in Georgian Bay With Noisy Party Boats Omitted, signalling the necessity of manual experience to this struggle with disillusionment, coming to terms with a failure to fathom, first-hand, the Canadian wilderness in fulfilling ways. After all, these works are undoubtedly objects, not immaterial images drawn from the vast expanse yielded by online searches (the new Sublime?). Sasaki plays the role of painter while playing with notions of censorship and nostalgia in Sea of Fog Mountain Range with Redacted Gas Station, applying vintage green Liquid Paper to redact a building at the base of a forested, riverside area. The concern with concealing reflects a ridiculous but hesitantly heartfelt attempt to travel temporally—not to somewhere identified with purity, but to a place that is simply free (at least temporarily) from irritants.

This is a similar emphasis on bodily awareness with the video installation A Camera In a Ball In a Mouth In A Dog In a Park. Passing by a projector and speaker mounted on a tripod, you first hear heavy breathing and commotion. Sasaki here strives to tap into the mind and movements of an excited canine creature, recalling avant-garde aspirations by expressionists and futurists, such as Franz Marc and Giacomo Balla, to associate animal consciousness with the cleansing of a corrupted humanity. As with these painters, the three-minute work tends toward abstraction, with frenetic and fragmentary footage of leaves, branches and grass—along with a momentary and meditative glimpse of a retriever, waiting to take hold of the camera-ball again. Sasaki is portraying a game of fetch, asking human viewers to consider it aesthetically, despite the fact that this projected landscape has been subjected to a dog’s dogged antics. The initial effect of this work—as a kind of novel stunt—rapidly wears off in favour of a refreshing contemplation of processes, such as animal respiration and cognition, or the limits of narrative and video technology.

Installation view, “I coined a word the other day, but I forgot what it was. It was a good one. It came to me in a dream,” 2017, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

Situated on scaffolding in the gallery, the large-scale LED work Every Combination of a Sixteen- Segment Display, 2017, cycles through the 65,536 unique configurations of digital sign segments, in a random order—so that every conceivable combination of forms momentarily appears and disappears. You may choose to venerate these glowing lines as a possible source of prophecy, or some other guidance needed in a time of increasing uncertainty—perhaps a form of AI figuring out how to communicate with unknown others occupying another plane of existence. While the work could be about communication and its impossibility, it may also be accessed as an abstract sculptural statement that is in a constant state of becoming. Indeed, Sasaki subverts a large-scale device that would normally be used for efficient informational conveyance, like directing cars or pedestrians, or serving an advertising function on a sizable scale.

A series of three rubbings of drawings (all from 2017) by modern and minimalist masters—Sol LeWitt, Josef Albers and Dan Flavin—are rendered by Sasaki in charcoal on paper. Frottage is here misused, given that it is a technique normally engaged to make an impression of a relief sculpture, for instance. While each drawing offers a rough, rectilinear shape that hovers on the page, collectively they seem to reflect both an unkind activity of sullying and a labour of love—a touching homage, as it were, exuding a poetic sense of protection. But the series is also about performing a single task resulting in a darkened veil. It may be taken on the level of a joke, but the procedural rigour required for its execution as a series allows for associations with the existential void. It is possible to consign these images to a realm of emptiness devoid of language or an absence that still may serve as a source of meaning derived from the simple act of applying a pencil without concern for utopian promises, a Romantic communion with nature, or the conceptual purity of mathematics (as LeWitt, Albers or Flavin may have had). These works do, of course, recall the careful erasure enacted by Robert Rauschenberg in Erased De Kooning, 1953, a relatively meticulous and pencilless execution resulting in a notso- blank picture that was obviously generated by hand, with many subtle imperfections and indentations. Indeed, the patient beholder may search Sasaki’s sooty strokes, moving beyond the gag, to consider what constitutes a coherent, creative idea in relation to drawing—a medium long associated with the activity of ideation and the manual act of creation.

Installed on an old-school, assertively sculptural, Sony Trinitron monitor—placed whimsically within a tipped-over table—the video To Change A Lightbulb, 2017, features an anonymous anti-hero (a recurring character in Sasaki’s videos) who samples from a pile of damaged lightbulbs with the goal of bringing forth light (or enlightenment). Tapping, prodding and snapping them in order to reconnect the circuitry contained within each broken bulb—this is a preposterous task, reminiscent of Fluxus-scripted gestures from the 1960s that anyone can perform. Sasaki offers up minor moments of anticipation, tinged with a feeling of failure and yet punctuated by flashes of brilliance, a luminescent loveliness. The premise may seem, once again, like a stunt, but then—encouraged by the repetition of a singular activity, with variation—verges deeper into a questioning mode tinged with humour. (How many artists does it take to “change” a lightbulb, or turn something useless into a sculptural and performative statement?) Sasaki here surveys other metaphorical territory—encouraged by many moments of cradling and care, applied until “currency” is established—that is both electric and aesthetic, and within a context of materialism that is resolutely removed from the digital illumination of the not-so-smart phone.

Paired within the same tablebased display is the silent video The Hero’s Journey, featuring two titular characters: red and yellow inflatable beings with perma-smiles, powered by extension cords. Like the lightbulbs, they have uncertain and intermittent lives, performing in a parking lot bordered by trees swaying in the breeze. Their encounter begins with a bow and a touching of heads. One then grabs hold of the other’s hands, and they frolic and flop about, presenting quick images of conflict and codependency. While engaged in aggressive acts, they also appear to perform amorous rituals of surrender or submission. Eventually, they seem to part ways, and at times are visible only as shadows on pavement. To our eyes, these crudely rendered figures may seem clumsy and abstract, but Sasaki’s manipulations and editing allow for a surprising emotional complexity that continues to flow through his work in general. ❚

“I coined a word the other day, but I forgot what it was. It was a good one. It came to me in a dream.” was exhibited at Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto, from September 14 to October 14, 2017.

Dan Adler is an associate professor of modern and contemporary art at York University.