John Kissick

Painter John Kissick likes to begin his artist’s statements (he’s done it twice, for exhibitions at Toronto’s Leo Kamen Gallery) with a quote from trans-avant garde painter Sandro Chia: “Today,” says Kissick’s Chia, “there are only mannerisms, and I am simply an historical nomad.”

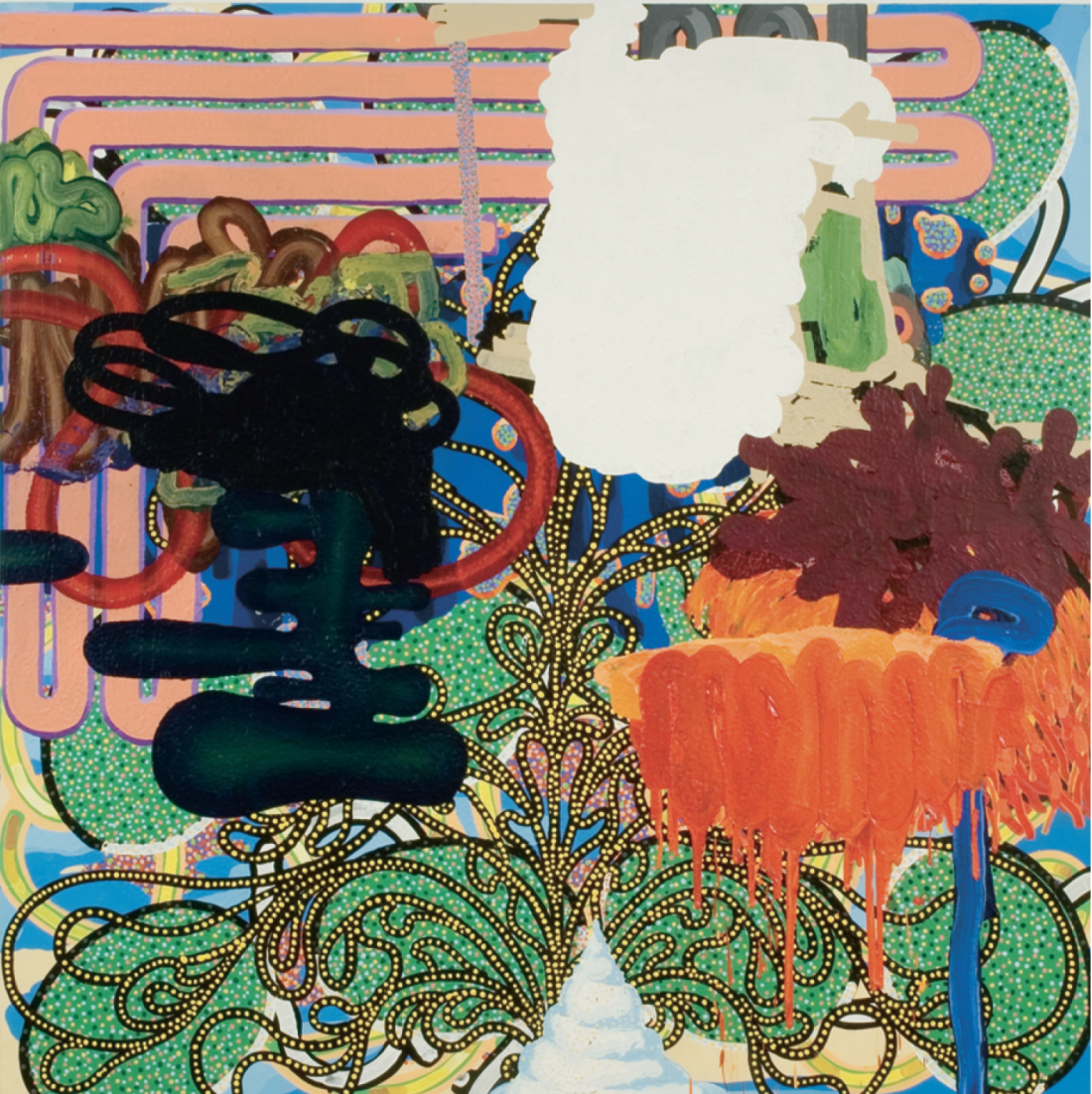

John Kissick, No. 3 2007, 2007, acrylic and oil on canvas, 66 x 66”. Photos courtesy the artist and Leo Kamen Gallery, Toronto.

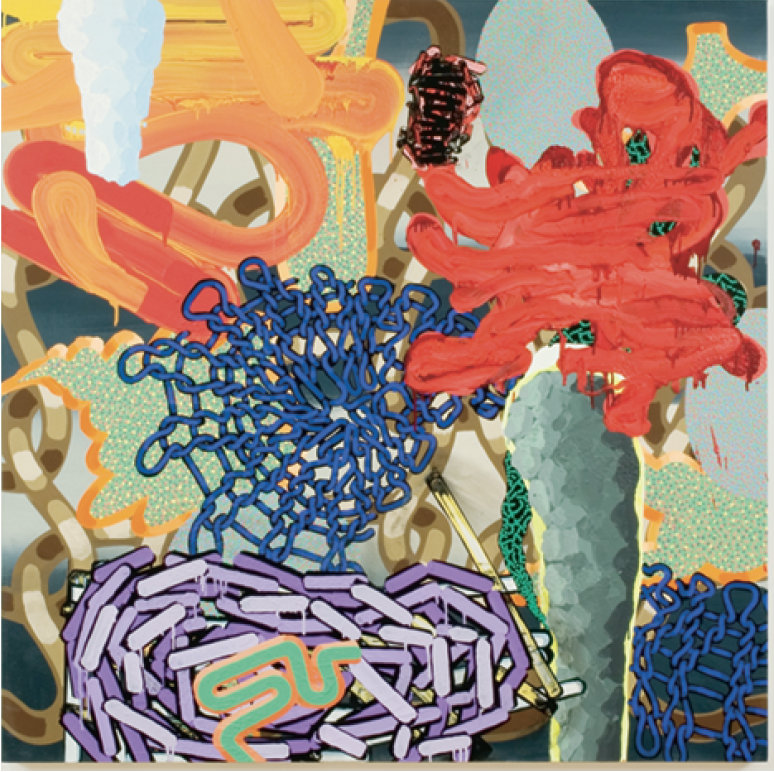

John Kissick is that quintessentially oxymoronic thing, a remarkably sensuous but infinitely wary painter who harbours deep and apparently distressing suspicions about both the origins and the procedures of his lush but carefully distanced—indeed, scrupulously ironized—painting practice. His canvases have grown steadily, inexorably, and, to add the anxious note that seems congruent with the painter’s positioning of his work, troublingly gorgeous, with each passing year. A typical new Kissick canvas is riotous with chromophilic frenzy and jostling with morphological plentitude. In a work like No. 4 2007, one of the 11 big paintings he showed recently at the Leo Kamen Gallery in Toronto, there are patches of imagery—or at least patches of painted incident—that jostle themselves into a kind of fervour of close-packed bliss: a goofy, flat, pink, cartoonish plant form outlined in mint green reaches up through the picture plane to meet a calligraphic or entrail-like gnarl of tube-like lengths of scarlet paint; horizontally located aqua-hued bladder-like things float like jellyfish at the upper right and, thicker now, wave up from the bottom like sea anemones; faux chains fall from the upper left, only to become involved with what look like strings of “beads” wound on a stiff vertical “rope” of dun-coloured pigment. It’s fun to type quotation marks around Kissick image-words—“beads” and “rope” and whatever else that is drawn from his fecund well of near-representational imagery— because those quotation marks, the linguistic residue of imagistic double-dealing on the artist’s part, point up Kissick’s cautionary distancing of his work from the spectre of painterly hedonism.

He has frequently alluded, in various of his artist’s statements, to his determination to construct paintings “that both expose and disguise their contingency to historical conventions of abstraction and ornament.” In the statement he composed for the latest exhibition, he noted that his recent combining of both oils and acrylic on a single canvas allowed for his colour’s moving from “the highly synthetic and garish (often signified by the acrylic) to mixes more reminiscent of older practices such as Abstract Expressionism.” He continues, “The colour thus acts both as a signifier of certain historical conventions (Op, Pop, contemporary fashion) as well as complicating the more atmospheric constructions of space typical of Abstract Expressionism (and the prevalence of mixing colour in the canvas through the act of painting).”

John Kissick, installation view, Leo Kamen Gallery, 2007.

I find it almost irritatingly smug and dispiriting to hear the painting procedures of Abstract Expressionism referred to as “atmospheric.” The paintings clang and clamour with complexity—if, by complexity, we mean a lot of shapes in a lot of hues jostled together in the performative, pressure-cooker space of the canvas. And lest this colour-shape jostling smack of an unseemly amount of painterly joie de vivre, Kissick has found a way of cooling down this idea as well: “I take it as a given,” he writes, “that both the repository of images I use, and the way I assemble my paintings are directly influenced by, and respond to a very contemporary cut and paste visuality prevalent today.” Kissick stresses, however, that his brand of compositional cutting and pasting involves neither the projecting of his “samples,” nor any compositional “planning in advance.” And unlike other contemporary artists who “mimic the flat screen and mediated aesthetic of the computer,” his new work “references the Modernist practice of finding the painting through the process of making it.” His paintings, he says, are diaristic rather than illustrative. “Diaristic” is perhaps a misleadingly personal word for the advent in the paintings of image next to, and upon, image—whether his images have come fibrillating from the artist’s teeming sensibility or have been downloaded from somewhere. It’s a revealing word for Kissick to use because, in this context, it appears to stand for a rather clerical means of imagistic acquisition rather than for the risk-everything rapture of, say, “invented.” It is clearly anathema to Kissick ever to open himself up to imprecations of seeking, rather than just finding. For although he is a naturally and inescapably sensuous painter (endlessly fighting the fall into hedonism), he is hellbent on denying himself the kind of painting all his instincts seem to lead him towards. I’ve never known a painter, in fact, who struggled so tirelessly to be able to have his pleasuring cake and eat it too.

John Kissick, No. 6 2007, 2007, acrylic and oil on canvas, 66 x 66”

The trouble lies in the fact that Kissick’s paintings are easy, and he wants them to be difficult. That’s why his morphological inventiveness— which is considerable—has to be tamed by the hands-off idea of cut and paste, and why the combining and collapsing of his various painting procedures have to be bound about by one of his clerical restraint-words like “hybridity” (as in, “I think the work responds in many ways to a variety of contemporary ideas around hybridity in paintings”).

The word “contemporary” tolls like a bell through Kissick’s thinking—where he uses it like a whip to fend off the coiled-spring tiger of old-fashioned painterly rapture. No point in getting mauled by your own instincts, I guess. On the other hand, it’s hard not to think of William Blake’s withering aphorism from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790–93, that runs, “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” For “wrath,” read “passion,” and for “instruction,” read “planning.” ■

John Kissick’s “New Paintings” exhibited at Leo Kamen Gallery from April 21 to May 12, 2007.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives in Toronto.