John Hartman

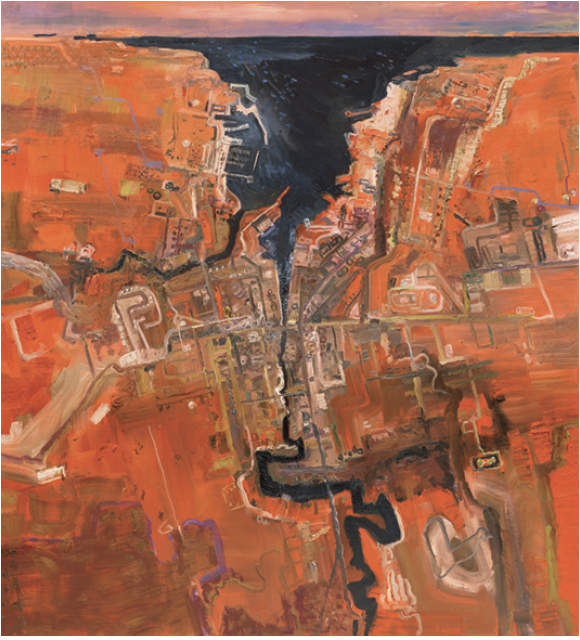

In John Hartman’s triptych, Halifax, the Maritime city expands on its massive canvases in a delicious mess of reds and purples. The MacDonald Bridge, unfurling like a fat red ribbon, snakes its way in to the heart of the peninsula from the smeary industrial shores of Dartmouth. The harbour, its pale waters stretched exaggeratedly around the contours of the city like a vast moat, spills into the Bedford Basin, where a fleet of warships sits, waiting.

The picture, commissioned by a major bank to commemorate 175 years of Halifax history, is an exercise not only in skewed perspective, but in time compression. There, in a mushroom cloud burgeoning over the city, is the Halifax Explosion, the 1917 disaster that razed the city’s north end. A small plane heading towards the horizon pays homage to the Swissair fl ight that went down near Peggy’s Cove in 1998; the flotilla a reference to the Great Wars.

John Hartman, T_he Thames from Swiss Re_, 2005, oil on linen, 152 x 168 cm. Collection of Richard Griffiths. Photos: See Spot Run Inc.

One of more than 18 in the exhibition, “Cities,” the painting, it is clear, is not a mere rendering of a place. It is, like the other works in the exhibition, a psychological portrait— a city depicted not only from a geographic standpoint, but from an emotionally driven one. Hartman’s cities, presented in sweeping aerial vistas, are organic and fluid, defying the concrete from which they were sprung. It is as if the artist has pulled back the skin of the metropolis, revealing the pulsing organs and muscle beneath, roads cutting across landscapes like veins and arteries. His buildings emerge from those same landscapes like living things, reaching heavenwards before curved horizons in Manhattan, or squatting down against the elements in St. John’s.

Colour, used effectively to capture urban temperament, is also vital to Hartman’s work. London, England, for example, is rendered in a dense patchwork of greys, greens and muted purples, the Thames a winding, muddied gasp of relief against an impossibly claustrophobic backdrop, the cloudy sky hanging low. In Parry Sound, the city almost disappears into its landscape, a picturesque muddle of earthy reds and coral pinks set down in vibrant blue waters. The Western Channel, Toronto, depicts the city in a haze of yellows with shadowy purples, the pale swoop of the Gardiner Expressway pushing its way towards a murky horizon, while Vancouver is a vast, bright painting, all optimistic blues and pinks.

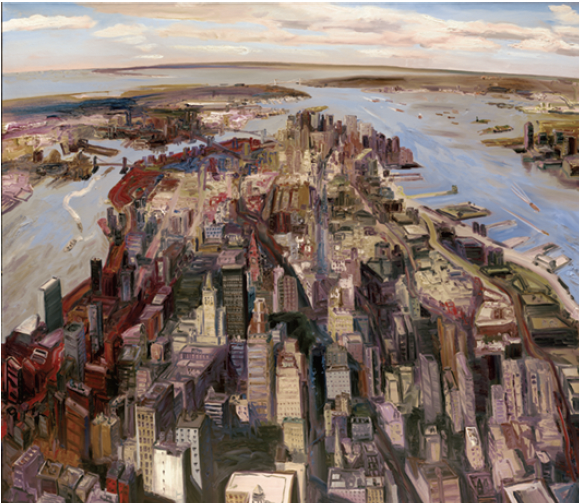

John Hartman, Lower Manhattan, 2006, oil on linen, 198 x 229 cm. Collection Sylvia and Jim McGovern.

Curated by Stuart Reid, the exhibition is a solid collection of richly rendered canvases with thick, satisfying painting. The effect of city upon city upon city is almost overwhelming in its evidence of our enormous human footprint on the planet. But these paintings do not judge—they merely look. In a conversation with essayist Noah Richler, who penned the lively introductory essay for the exhibition’s beautiful catalogue, Hartman is quick to point out that his works are not political commentaries on the environmental impact that cities have had on our planet. “I’m interested in how the erection of cities has altered the sites they’re built on, but I’m not actually attaching any moral value to these phenomena. I’m not saying that cities are bad because we pollute the harbours, for instance, but that we have to realize that what we do will affect landscapes by virtue of our using these sites. I really do see us as part of the landscape, and cities as examples of an extraordinary overlay of human activity.”

The exhibition also includes Hartman’s preparatory watercolour sketches and ink drawings marked out in accordion-style notebooks. David Milne, an artist Hartman has said he admires, is present in the loose, unencumbered touch of these on-location paintings. The artist’s process involves making numerous studies of a place before commencing—taking aerial photographs from planes, making drawings from the tops of tall buildings, and collecting postcards and other images.

John Hartman, Owen Sound, 2005, oil on linen, 168 x 152 cm. Collection Brian and Susan Lahey.

The finished paintings become collections of these experiences. In a very fine rendering of Lower Manhattan, the island’s buildings, hard-edged in the foreground, are reduced to thick, swabby lines in the back. The city is clearly New York, but the buildings have been reduced to a flattened carpet, the Brooklyn Bridge to a single smear against a fantastic, wider-than-life horizon. They are pictures that are at once real and interpreted, something the artist refers to in his conversation with Richler as “psycho-geography.” “I realize, of course, that what I do is highly subjective and that what I choose to capture reflects my own take on the place,” Hartman is recorded as saying in the essay, later expressing that he is excited by the idea that someone might be able to point at a painting and find a familiar landmark, a picture of home, perhaps, in a worked bit of paint. ■

John Hartman’s “Cities,” organized and circulated by Tom Thompson Memorial Art Gallery in Owen Sound, Ontario, was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax from March 5 to April 22, 2007. The exhibition will continue on an extensive cross-country tour (with stops in London, England, and in New York) through 2009.

Meredith Dault is a freelance writer based in Halifax.