Johannes Vermeer

In the arts, there are a very few figures who, by virtue of extraordinary achievements, have a mystique that sets them apart from even their most esteemed contemporaries. Johannes Vermeer, 1632–1675, certainly is one such figure. The story of his rediscovery in the 19th century by Étienne-Joseph-Théophile Thoré; the cameo appearance of his View of Delft, 1659–1661, in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; even the infamous Han van Meegeren forgeries, which fooled some experts, and the theft of a Vermeer from the Gardiner Museum in 1990—this publicity emphasizes and reinforces his singular status. Were the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum to stage a show of Pieter de Hooch, Frans Hals or even Rembrandt, they would not have gathered an international audience such as this sold-out show received. Tickets, which were reasonably priced by the museum, were for sale by scalpers online for thousands of dollars.

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing, 1664–67, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer Jr, in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer.

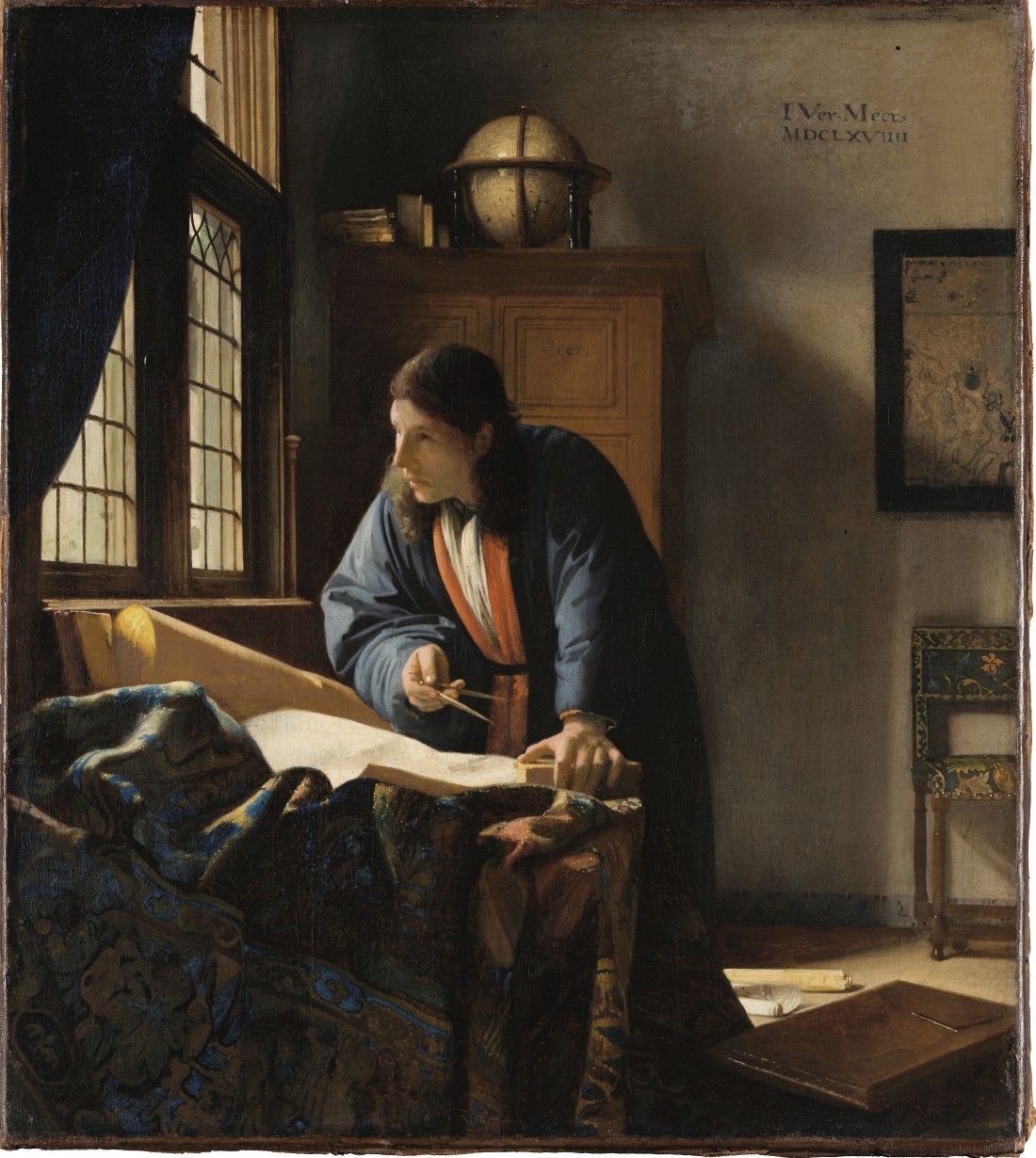

Why has Vermeer acquired this status? Compared with the only two other European Old Masters who arguably also have a similar mystique—Caravaggio and Piero della Francesca—his subjects are limited. In the first gallery in the Rijksmuseum are his three early pre-stylistic sacred scenes (Vermeer was Catholic by conversion), and in the next room are his two cityscapes. After that, he hardly shows scenes outside of his house—indeed, he doesn’t even provide a view through the windows. With one exception, The Geographer, 1668–1669, these genre pictures show women alone, or with men (who are usually in the background) in domestic interiors. Perhaps, the catalogue suggests, he was depicting his own house. Some of the women are drinking or reading, while others play virginals or listen to letters being read by servants. Young and pretty, not sensual but not totally distant, they are responding to something we can usually see. We don’t, however, know what they are thinking. Caravaggio’s exhibitions trace his development from the small early genre pictures to the early Roman altarpieces, and then the dramatic developments taking place when he moves southward to Naples, Malta and Sicily. Piero scholars have to decipher the elaborate iconography of his Arezzo frescoes. By comparison, the 28 pictures in this show, none of them physically large (all but six of the works generally attributed to Vermeer), display a limited variety of themes. No landscapes or altarpieces here. A short streetcar ride from the Rijksmuseum was “Rembrandt and His Contemporaries: History Paintings from The Leiden Collection” at the Hermitage Amsterdam, 4 February–27 August 2023. In that exhibition, which was not crowded, you see Vermeer’s contemporaries portraying a great variety of subjects. But none of these works have the mystique of many of Vermeer’s. Thanks to the classical book Vermeer, 1952, by Lawrence Gowing, and Aneta Georgievska- Shine’s luminous Vermeer and the Art of Love, 2022, there are good explanations for why he is a distinctive painter. Certainly today no one could confuse him with the other Dutch genre painters such as Gerard ter Borch, Jan Steen or Jacob van Loo, to name three contemporaries.

As I wandered through the crowds in this exhibition on three occasions, I puzzled over this situation. I could certainly see how good Vermeer’s paintings were, but why were they so popular with this larger public? What, I asked myself, was driving this extreme response? It happened that the gallery shop had a short paperback book new to me, Timothy Brook’s Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World, 2007. An academic sinologist by profession, Brook focuses on some objects in these pictures: a wineglass (a Dutch copy of Venetian glass), a hat (Canadian fur); the Turkish carpets and Chinese pottery, the silver coins (Peru), and of course the maps on the walls and the globe in The Geographer. He is interested in explaining how this stay-at-home artist (Vermeer never left Holland) could respond to the world economy centred on Amsterdam. Brook provides a marvellous account of the Dutch trade networks. What interested me, however, was the implications of his account for understanding the huge popularity of this exhibition.

Johannes Vermeer, The Geographer, 1669, oil on canvas. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

Vermeer seems, by virtue of his few subjects, a very limited artist. If, however, we consider his relationship to the Dutch global trading system, as described by Brook, we see that his true implicit subject, the world economy, is very large. For while the sites shown are mostly Dutch house interiors, these objects—glass, hats, carpets, pelts, coins—come from the entire trading world. In an earlier review, published in the Brooklyn Rail, I discussed a recent exhibition tracing the response to the global Dutch trading of another stay-at-home artist, Rembrandt. Compared with Vermeer, he responded to a wider array of exotic artifacts; for example, Rembrandt copied Persian miniatures and clothed his models in Eastern attire. So, while the form of his art was European, the contents sometimes came from elsewhere. Vermeer’s use of artifacts from the global trade relates to what I have called his mystique. He presents what seems to be a marvellously attractive visual world, a place of perfect harmony. Here, Proust offers another perspective that deserves consideration. When his (imaginary) novelist Bergotte goes to a Parisian art exhibition to see the View of Delft, Bergotte sees a yellow wall that is different from what he remembers. Then he is inspired to realize that his last books should have been written, he says to himself, with a sensibility more like the painting of the yellow wall. And, feeling a spell of what he thinks is indigestion, he sits down on a sofa in the gallery, falls to the floor and dies. Et in Arcadia ego: even in Arcadia there is death. That’s what Bergotte discovers. (Nicolas Poussin did two paintings containing that inscription.) And here, I am suggesting, in Vermeer as seen by Proust, we find the same conception, for when looking at this very beautiful cityscape, Bergotte finds death. The catalogue of “Rembrandt’s Orient” makes a provocative suggestion. Responding to the present political crisis, and the awareness of the problems of European colonialism, it notes, “the wealth of the Dutch upper class was the result … of violence and oppression in the Far East and came at high human cost, even among the country’s own sailors.” Literary scholars have noted that the price of Jane Austen’s country houses was English imperialism. Here I am only making the same point about Dutch painting subjects. Vermeer’s scenes, as I have said, are very harmonious. This serenity is the basis for what I have called his mystique. But what we see in these paintings are the products of the Dutch global economy and, in his house interiors, the prosperous everyday life that they made possible. If, however, following Brook, we inquire into the sources of this beauty, then we may feel a certain ambivalence. This, after all, is what Walter Benjamin claimed when he famously wrote: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Artistic beauty has its price.

This analysis may suggest why Vermeer is so popular. He offers a very partial vision of the consequences of a global world economy, showing the handsome people and the serene harmony of his interiors but not the human price of the artifacts they contain. What in his pictures remains out of immediate sight are the costs of European wealth and comfort. Should we criticize his paintings for their artful partial world view or admire them for presenting very positive images of prosperity? That question I cannot answer; it’s my aim to interpret the art that is on display, but I cannot offer here a moralizing response. ❚

“Vermeer” was exhibited at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, from February 10, 2023, to June 4, 2023.

On wild art, see David Carrier and Joachim Pissarro, Wild Art (London: Phaidon, 2013) and Aesthetics of the Margins/The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2018). Carrier’s In Caravaggio’s Shadow: Naples as a Work of Art (2024) is forthcoming.