Joan Miró

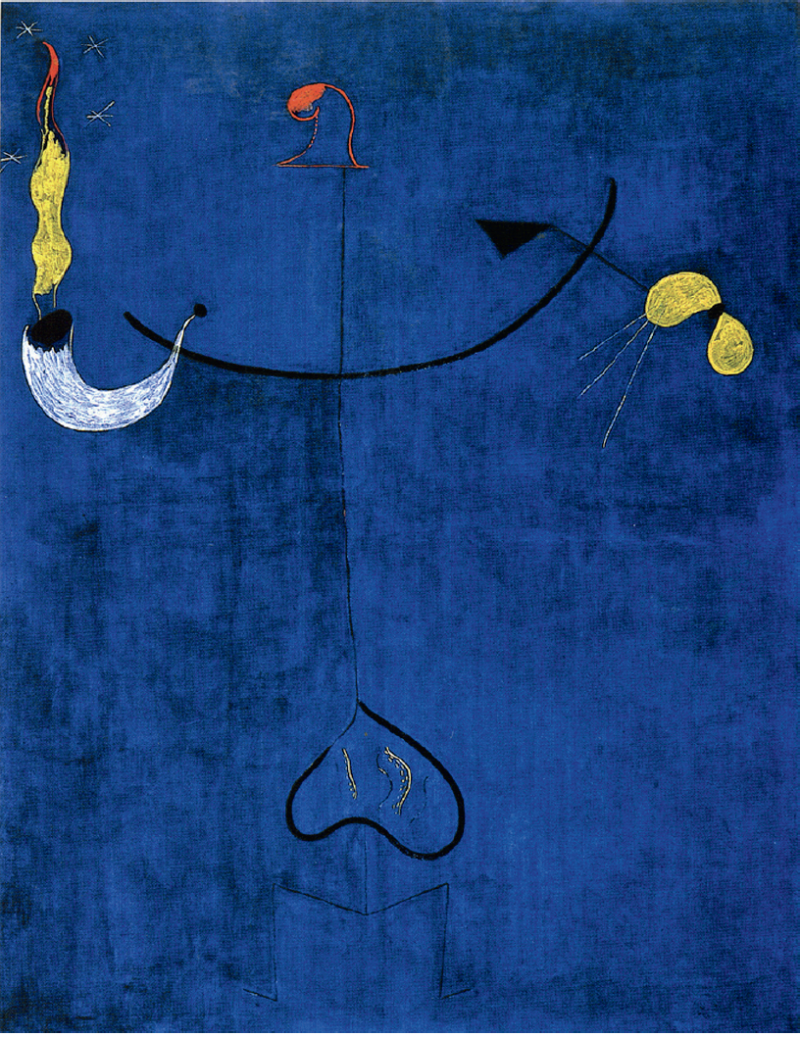

Joan Miró, Catalan peasant with guitar, 1924, oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm. ©Successió Miró, Palma de Maliorca. Courtesy: Funació Joan Miró, Barcelona.

Here’s an exchange, from 1927, between André Masson and Henri Matisse: Masson explained: “I begin without an image or plan in mind, but just draw or paint rapidly according to my impulses. Gradually, in the marks I make, I see suggestions of figures or objects. I encourage these to emerge, trying to bring out their implications even as I now consciously try to give order to the composition.” “That’s curious,” Matisse replied. “With me it’s just the reverse. I always start with something—a chair, a table—but as the work progresses I become less conscious of it. By the end, I am hardly aware of the subject with which I started.”

Visiting “Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape” at Tate Modern in London, it became clear that Miró occupied both positions at different times, and, quite possibly, both positions while making a single work. Perhaps this is why, although a century-spanning member of the modern art pantheon, he remains somehow elusive. The Tate contributes to Miró’s resistance to categorization in the way the current exhibition is organized, by offering two differing contexts for an appreciation of the artist’s work. First, through the presentation of the paintings and sculpture with accompanying texts, the gallery seeks to connect Miró’s work to European politics, particularly the position of Catalonia and, second, with adjoining displays titled “Poetry and Dream,” to locate Miró’s work in relation to a broad range of other practices associated with Surrealism. These two strategies can sometimes seem contradictory; the fantastic side of Surrealism (and of Miró’s work) appears to have a relatively oblique relationship to contemporary events. The gallery’s information panels, locating the work in a timeline of, for example, the rise and fall of the Spanish Republic, ask the viewer for a more direct interpretation. In fact, Miró’s oeuvre is capacious enough for us to negotiate this complication.

Joan Miró, His Majesty the King, 1974, acrylic on wood and bronze and iron, 254 x 22.5 x 43 cm. ©Successió Miró, Palma de Maliorca. Courtesy: Funació Joan Miró, Barcelona.

The exhibition is arranged chronologically, with text panels reminding us of events contemporaneous with the making of the works. The catalogue continues a scholarly consideration of work versus history throughout the artist’s life. Clearly, Miró was not a polemical painter, but the complexity and nuance of his paintings’ reactions to the events of his times are one of the great pleasures of the show. As the Republican government in Spain neared defeat in 1938, Miró painted Nature morte au vieux soulier and wrote, “Despite the fact that while working on the painting I was thinking only about solving formal problems…I later realized that without my knowing it the picture contained tragic symbols of the period—the tragedy of a miserable crust of bread and an old shoe, an apple pierced by a cruel fork….” It’s an extraordinary painting, predominantly black, turquoise, red and yellow, the colours of a nightmare. There is a working through of subject here, from the quotidian to the symbolic. This is representative of one end of a spectrum of Miró’s responses to notions of structure and improvisation: structure standing for working from the real, for finding a symbolic language in painting, and improvisation standing for a creative and generative lack of premeditation. The Tate’s “Poetry and Dream” display, particularly the central room devoted to Surrealist painting, offers an opportunity to reflect on themes and tendencies in painting that access conditions of the unconscious (primarily either by automatism or attention to dreams). Matthew Gale writes in the notes for this work: “The ‘revolution of the mind’ sought by Surrealism drew upon the uncensored creative impulses of the unconscious. [For] Joan Miró and Jean Arp, automatic techniques of drawing or writing without premeditated themes or correction opened a floating world of abstract associations.”

At the Tate there is a room of Miró’s paintings titled “Constellations,” made in Normandy in 1940. These are small works on paper, executed in gouache and oil wash. The paintings are playful and childlike, their small scale allowing us to imagine Miró inventing the compositions as he worked. Needle-like lines link fantastical creatures to stars and moons. The reds, blacks and blues are impenetrably opaque against transparent, stained backgrounds. There is a measure and deliberation in the way that line conjures form; this is not the automatism of, say, a Masson drawing but rather a negotiation between structure and improvisation. As Briony Fer has pointed out, Miró was working at a time when these two aspects of modernity “were coming to be seen by others, not as complexly linked, but as directly opposed.” Miró seems always to have resisted this oppositional notion—in fact an avoidance of fixed categories pervades the work in the show. Geometric painting collides with the organic, emptiness with a filling of the picture plane that can become ornamental. The term, “formless,” has been applied to Miró’s work (initially informes by Bataille), formlessness constituting a third term standing outside of formal or binary thinking. This feels right. Walking around the galleries at the Tate, it seems the paintings are neither definitively this nor that. They show us Miró’s awareness of what Fer has called “the shifting ground of representation.” The Tate show, then, is a catalogue of instances of Miró’s resistance to categorical descriptions of the way things are, whether this was the privileged position of the work of art or the social and political conditions he experienced. There are two periods of Miró’s work included where his antipathy towards what might be called the defining characteristics of the medium of painting and of the social milieu becomes more pronounced and assertive. These are the “dream” paintings beginning in the late 1920s and the “burned” paintings made in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

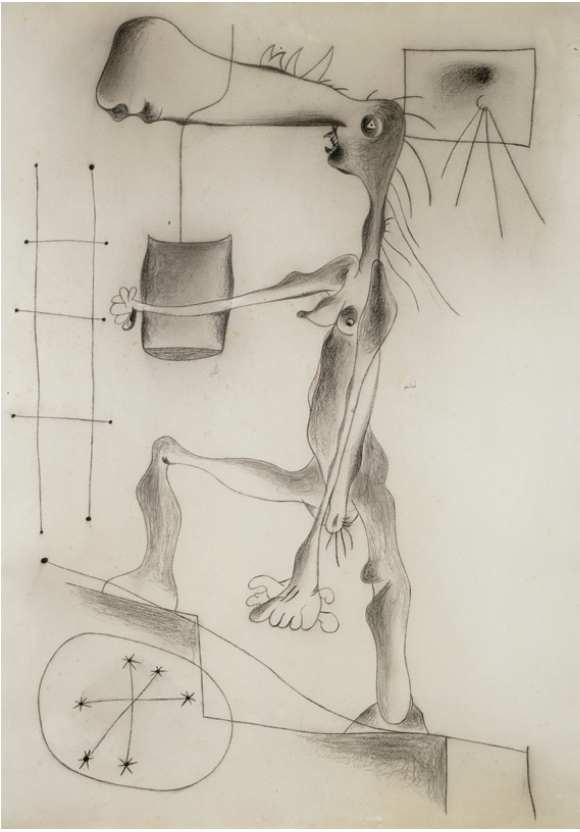

Joan Miró, Naked Woman going upstairs, 1937, charcoal on card, 78 x 55.8 cm. ©Successió Miró, Palma de Maliorca. Courtesy: Funació Joan Miró, Barcelona.

A few years ago, in his influential essay “Provisional Painting” (Art in America, 2009), Raphael Rubinstein proposed Miró as a precursor to a number of contemporary painters, among them Raoul de Keyser and Michael Krebber. Rubinstein was responding to the MOMA show “Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting, 1927-37,” where the unfinished, cursory nature of many of Miró’s paintings of the period seemed to foreshadow more recent developments. At the Tate, the works date from 1917 to 1974, but the vital years covered by the MOMA show are well represented: Painting (The Bullfighter) from 1927 is a brown canvas partially stained with white, featuring a loose black rectangle, dashed off super-skinny crossed lines and crowned with a red dot. It does look like the ancestor of the kind of deliberately awkward painting we might encounter today. In 1931, Miró told a Spanish journalist that his aim in this period was “to destroy everything that exists in painting.” This painting from 1927 is a work that is assertively unfinished, a challenge to the viewer, then and now—a challenge to come to terms with a work that appears to actively undermine any preconceived notions we might have about painting. It is an intention he revisits with the “burned” paintings of the ’60s and early ’70s. As the catalogue essay puts it, Miró returned to the theme of the “assassination of painting” with these burned works, which were first exhibited in 1969. They are installed at the Tate as when first shown, as free-standing objects rather than on the wall, and were a response to the climate of political violence in Franco’s Spain, and particularly Catalonia, during that period. There is certainly a sense of violence to them. The burned paintings are works of protest but cannot be seen, except in a literal sense, as expressing Miró’s earlier destructive aspiration towards the medium. There is a self-consciousness and theatricality here that is unusual in his work. Their making is a social/political act, perhaps, rather than a working through of ideas in painting. In 1979 he wrote “…when an artist speaks in an environment in which freedom is difficult, he must turn each of his works into a negation of the negations, in an untying of all oppressions, all prejudices, and all the false established values.”

“Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape” shows us an artist working, with imaginative ambition, over a 57-year period. Very few of Miró’s contemporaries painted with the intelligence we see in this exhibition, even fewer with such a consciousness of internal and external factors that might inform the work. We are accustomed to seeing contemporary painters deconstruct the notion of the masterpiece by risking de-skilled and deliberately slapdash ways of making work. It can be an invigorating trait, but in these seen-it-all days (at least in painting), it can appear as a self-conscious construct. This exhibition shows an artist who had an audacious engagement with cultural expectations throughout his life and, for a particular period between the world wars, a remarkable sense of daring and vitality. An echo of this reverberated along the south bank of the Thames this summer. ❚

“Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape” was exhibited at Tate Modern, London, from April 14 to September 11, 2011.

Martin Pearce makes paintings and drawings. He teaches in the School of Fine Art and Music at the University of Guelph.