“Jiggery Pokery”

“Jiggery Pokery,” the title of a two-person show at the Winsor Gallery, is a curious old British expression. Meaning deceitful or dishonest behaviour, it is a delight to say, burbling out of the mouth easily and suggestively, like the kind of humbug it denotes. At first glance, however, it is difficult to apply this term to the sincerity of the two- and three-dimensional works on display. After a more considered viewing, though, you begin to understand that Angela Grossmann and Drew Shaffer each examine the kinds of behaviours that human beings assume, often less than truthfully, in order to accommodate social and sexual expectations. Both artists explore gendered identity, sexual stereotypes and the construction of desire, with all their attendant lies and subterfuges.

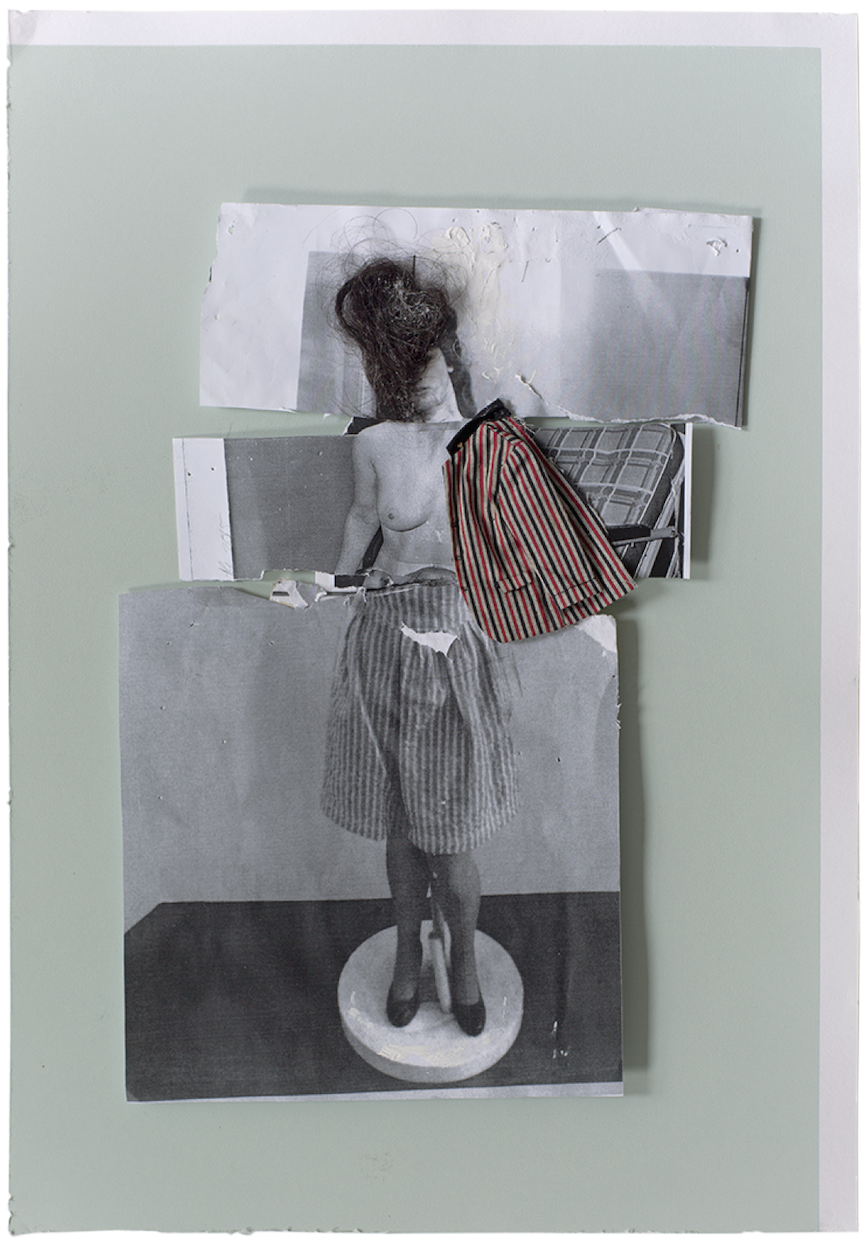

Grossmann is a well-established artist with many shows and much critical acclaim to her credit and Shaffer is a little-known “emerging” artist who has taken a long hiatus from exhibiting. Still, some of their strategies are similar. Both employ found images or materials in the expression of thwarted emotions and conflicted selfhood. Grossmann’s small, wall-mounted collages are composed of torn and crumpled copies of old photographs, onto which bits of shredded fabric, strands of synthetic hair and articles of doll clothing have been glued. Shaffer’s larger, freestanding sculptures are constructed out of an assortment of new, antique and salvaged materials and objects, from feather boas to fake grass. Both artists build dialogic or narrative elements into their work—Grossmann through the unsettling images she creates and Shaffer through his long and somewhat anguished titles.

Grossmann’s new works, based on vintage erotica, grew out of a series of mixed-media collages she exhibited last April at Kardosh Projects; both series consider desire within the context of eroticized female identity. Curated by art historian Lynn Ruscheinsky, the Kardosh show addressed the idea of gender as performance, especially in the awkward combinations of male and female faces and body parts. Elements of theatre were also evident in the stage-like settings in which Grossmann placed her figures, and in the puppet strings attached to many of them. In “Jiggery Pokery,” however, Grossmann focuses on patched together images of women rather than on a conflation of male and female. Still, she continues to tear, crumple and recombine the erotic photos in ways that challenge issues of sexual allure and the male gaze. A few of these more recent figures are also attached to strings, again suggesting a lack of personal agency. Although voyeurism is obviously referenced in the source material, it is also persistently undermined in Grossman’s work, through both the disruption and misalignment of the original images and the use of ragged bits of fabric and old doll clothing, such as miniature striped briefs, to cover obvious sexual attributes and erotic accessories.

Drew Shaffer, I Hate What You’re Doing to Me, 2015, mixed media, 40 x 40 x 12 inches. Courtesy Winsor Gallery, Vancouver.

Grossmann is extremely deft at amplifying, to the point of ridiculousness, elements of sexual titillation. The silly little doll undies, overlaid on the photographic representations of women’s underwear, subvert the idea of panties and bras as articles of enticement. Oddly big and baggy as they seem now, the undergarments of the 1920s and 1930s would have transmitted a sexual charge through the colour, weight and texture of the fabric used. Grossmann satirizes this frisson too by applying scraps of old, grubby, shredded pink satin—and unexpectedly coarse, bright, non-erotic fabric and doll garments—to her collages.

The strands and blobs of synthetic hair Grossmann messily glues over the photographed hair of the original models function in the same mocking and disruptive way. The anonymity of the models—their non-personhood—is powerfully conveyed. Grossmann also takes on the chronic disconnect between what women actually look like and the idealized body image against which they measure themselves.

Despite their long titles, Shaffer’s surreal art is more difficult to parse than Grossmann’s. Constructed with great technical facility and an acute attention to details and finish, these sculptures are almost hermetic in their presentation, as if we were viewing, at a great emotional distance, someone else’s nightmare. In his statement, Shaffer says that this body of work is “about desire: what we want, why we want it, what happens to us when we get it, and what happens to it once we’ve had it.” In preparatory notes he shared with me, Shaffer writes that his strategy is to use playful motifs “to talk about uncomfortable, unjust and inequitable relationships between people.” It is not surprising, then, that the titles of his work and their airtight construction suggest that desire has been not so much imagined, met and reimagined as it has been thwarted, distorted and sealed off from an experience of wholeness.

Angela Grossmann, Jacket, 2015, collage and mixed media on paper, 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy Winsor Gallery, Vancouver.

The works range from a suffocatingly featureless portrait bust sewn out of bright red quilted fabric of the kind used in winter clothes to an antique metal scoop whose interior has been fitted with black leather upholstery. The sculpture titled I Hate What You’re Doing to Me consists of a C-shaped tube—a detached and contorted pair of legs—dressed in blue jeans, with a life-size, papier-mâché foot protruding out of one pant leg and a stump, to which has been attached a curious device, sticking out of the other. The device consists of a puffy ball of marabou feathers mounted on a thin metal stand and fitted with a handle. When the handle is turned, the feathers tickle the fake foot. Although there are elements of fetishistic and masturbatory humour here, there is also distress. Both form and title alert us to a painful element of compromise—a figurative as well as literal contortion—in order to accommodate another’s expectation of pleasure. One man’s titillation, it seems, is another man’s torture.

And You Never Will While You’re Living Under My Roof is a large, grey head covered in overlapping asphalt and gravel shingles, with no eyes, ears or mouth, only a bulbous nose fashioned out of an antique metal finial. The effect is that of a disapproving entity intentionally closed off from another’s reality—a benighted parent, perhaps, in denial of a child’s sexual identity. Or perhaps this bust is an admonishing self-portrait, that of a being who has internalized his parent’s abusive attitudes and behaviours.

In their juxtapositions of disjunct forms and materials and their flirtations with the grotesque, Shaffer’s artworks evoke Salvador Dalí’s brand of Surrealism. That is, they are unsettling, at times amusing, but also in a sense, impermeable because of their tight construction and fastidious finish. The installation is somewhat troublesome. Shaffer’s sculptures are not a particularly good fit with Grossmann’s collages: his works overwhelm hers in scale, form and colour. Unfortunately, Grossman’s small, mostly black and white images have been framed in white and almost disappear into the gallery’s big, white walls. Still, her expressive messiness continues to assert a presence, opening her work up to our engagement and interpretation. Shaffer’s imagination and technical facility work impressively together, but at the same time, they threaten to preclude our becoming fully emotionally invested in his art. ❚

“Jiggery Pokery” was exhibited at Winsor Gallery, Vancouver, from October 15 to November 14, 2015.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.