Jessica Groome

For Henri Bergson, memory doesn’t follow perception but is contemporaneous with it, notes Giorgio Agamben in his recent book The Signature of All Things. Bergson is concerned with déjà vu, which he calls “a memory of the present,” a state that “is of the past in its form and of the present in its matter.” If we borrow Bergson’s formulation and divert it somewhat, it might describe, if not the act of painting, then the fact of it. A painting that shows evidence of its making is always “of the past in its form and of the present in its matter.”

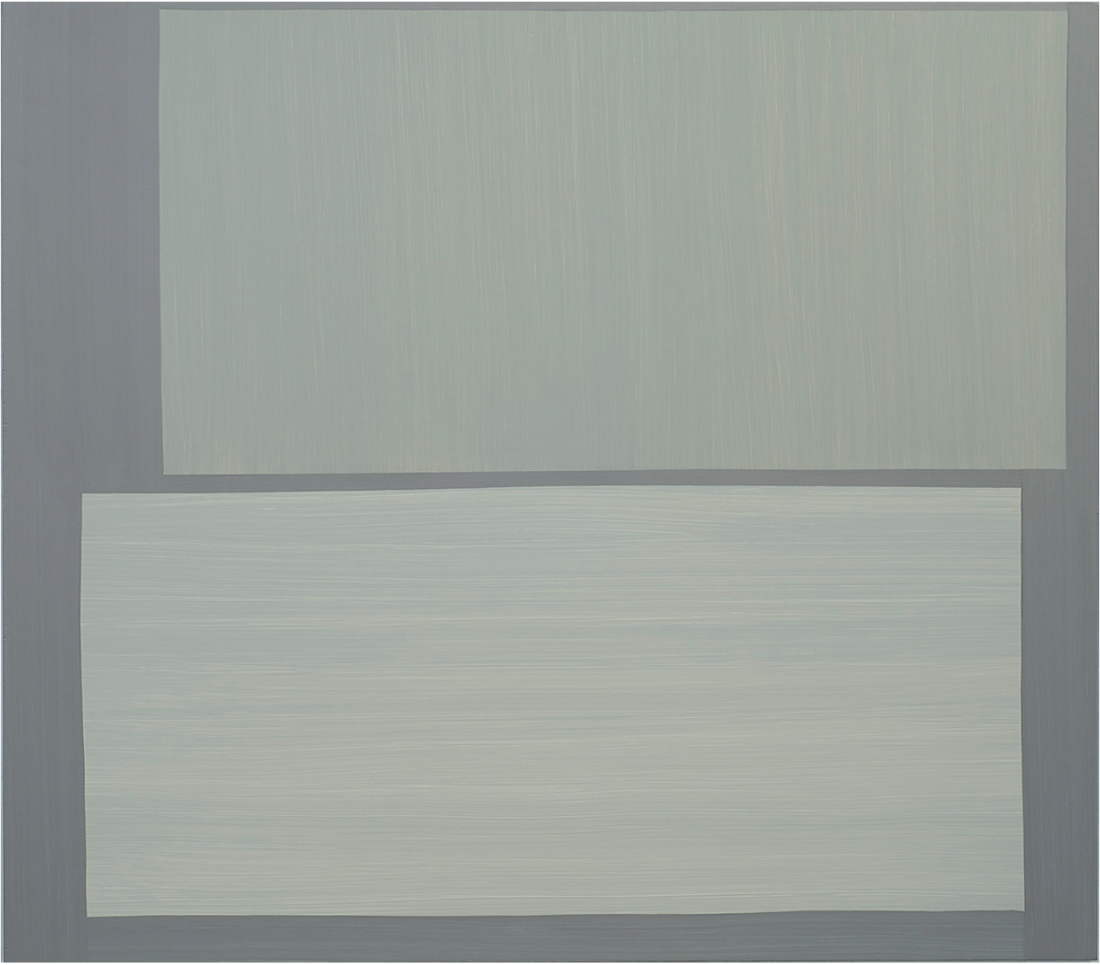

Jessica Groome, Untitled (northeast), 2011, oil on panel 43 x 51.” Courtesy Wynick/Tuck Gallery, Toronto.

The thinly smooth, oil-on-board surfaces of Jessica Groome’s paintings are beautifully balanced in the registers where visual perception meets memory. They show Groome’s brushwork and are also extremely sensitive to the frequencies of light. Her colours, on long viewing, evade being accurately named, but her forms and lines often do invoke simple names: windows, horizon lines or almost-familiar shapes. The two window shapes in Untitled (northeast), each with their different tonality of light blue-grey, seem to occupy different moments of weather mimicry. As material surfaces they appear matte when viewed head on, but from the side are glossy and softly rutted in places like a gentle ceramic glaze. They easily catch the day’s changing natural light and transform with it, and then at the end of the day settle into sedentary greys that are capable of invoking melancholy.

Untitled (northeast) takes its name from the direction of the brushwork that makes up its two “windows” (one is brushed vertically, the other horizontally) and lends the work a literary as much as literal sense of weatherly geography. These windows are framed by, and seem to be cut out from, a ground of metallic silver. Although the borders are uneven, they can be playfully read as the silver of gilded picture frames or metal window mouldings. Depending on the light and the position of the viewer, they may shift from a refractive, active silver to—when their brushy texture breaks up the light and holds it in place—something like a matte grey. At the thin, upper edge of the work, the silver pigment seems to disappear altogether, becoming a neutral blankness that reads not so much as colour as simply an “edge.” That the relative objecthood of Untitled (northeast) can depend on the position of the viewer (it should be added that Groome doesn’t use interference paints) brings into play the inevitable and habitual movement of the body on viewing a painting.

Installation view of Jessica Groome’s exhibition “The Top Tips Nearly Kiss,” 2011. Courtesy Wunick/Tuck Gallery, Toronto.

In Untitled (notch), Groome uses wide areas of bronze in place of silver as a border or ground. But depending on the light—natural or artificial—and the state of the viewer’s perceptual apparatus, this pigment can seem brown or even a garish gold. These shifts beautifully mimic the non-homogenous and changeable nature of consciousness. Untitled (notch) has another subtle aspect that can go unnoticed at first glance: a slim rectangle cut away from its bottom edge that makes it a kind of shaped canvas without the canvas. The seemingly imprecise, handmade painted line of Untitled (notch) is analogous to the cut-out collage work that is also part of Groome’s practice. But the painted surfaces do what paper collage can’t: allow themselves to fall away into an appearance of distance. Surface pigment falls into a phenomenological realm that produces visual memory. It makes the present into a virtual past.

Elizabeth McIntosh was Groome’s mentor as an undergraduate at Emily Carr (Groome has just been awarded her MFA at Guelph University) and her influence is palpable. Another of McIntosh’s West Coast students, Monique Mouton, comes to mind, along with Jack Chambers’s Silver Paintings and Ben Nicholson’s luminous, semi-abstracts works of the 1940s and ’50s, into which he adapted the blues, greys and browns of his working and living environments at St Ives. Yet Groome’s intelligently sensitive concerns and playful dialectics mark her approach as promisingly unique. Others in the art world seem to agree. She is the 2011 winner of the coveted $25,000 Joseph Plaskett Award. ❚

“The Top Tips Nearly Kiss” was exhibited at the Wynick/Tuck Gallery, Toronto, from May 7 to June 4, 2011.

E C Woodley is an artist, composer and regular contributor to the pages of Border Crossings, Art in America and Canadian Art.