Jenn Norton

Jenn Norton, Transfer Station, 2007, video still, single-channel animation/ video hybrid, 24:24 minutes. Images courtesy the artist and Macdonald Stewart Art Centre.

Critics can go fuck themselves,” says performance artist Vladimir Kunst in an exclusive interview with Corky Whittaker from PSnews, who had just asked what he thought about being labelled as “sensational.” “See, they’re the puppets,” he adds, smoking furiously. “Puppets controlled by their paycheques.” Classic Jenn Norton. The Guelph-based video artist’s cheeky piece, entitled Transfer Station, is a cross-cultural romp through the sugar-coated, hyperbolic roller coaster we know as TV trash culture, and where the visual artist fits—or doesn’t fit—in the mire. Fashioned in a way that keeps an auric glow around the creative class, around being self-conscious and self-directed, Norton finds a way to state that explicitly, even if it is a bit brazen. Just as her past pieces suggest uncomfortable visits to her inner underworld— like 2002’s Excess, or televised claustrophobia in 2003’s Student in a Locker—Norton continues to closely visit her virtual creations. But adds something new. She peels back the plastic and takes a look at herself, no holds barred.

Jenn Norton, Les Poupées Russes, 2007, installation view.

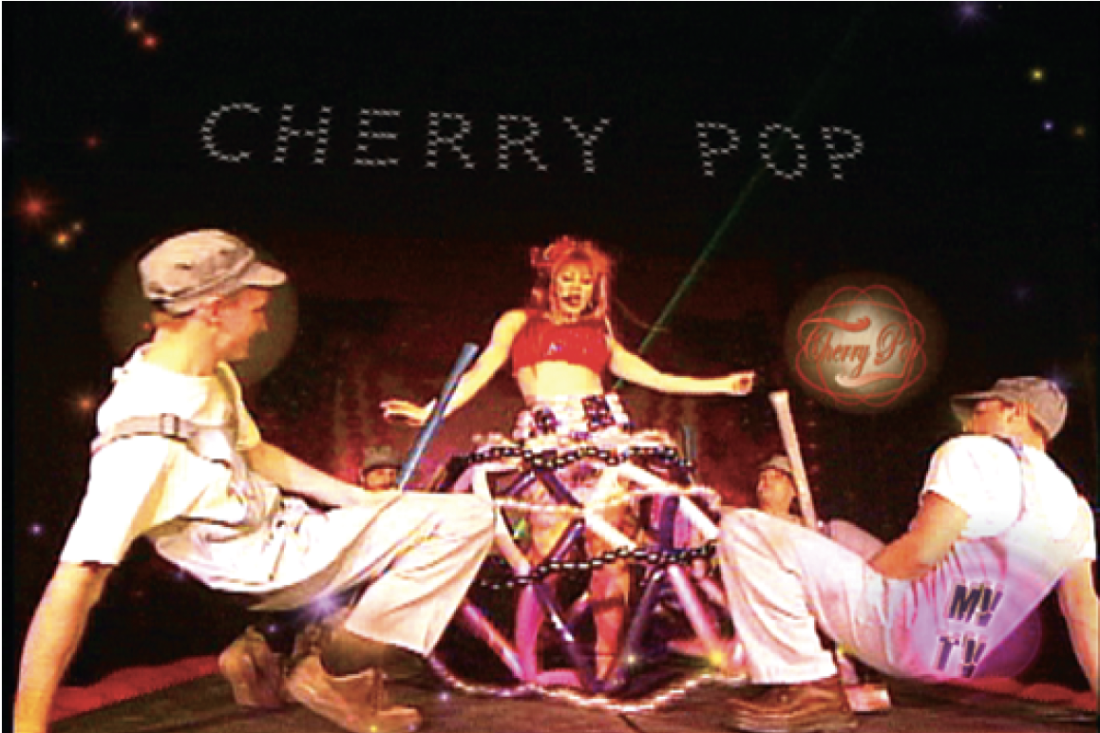

“The Insatiable Appetite of Russian Dolls” is her first solo show since graduating from the University of Guelph’s MFA program last year, and uses the famed folk matryoshka doll (the wooden stacking dolls that are placed inside each other) as a way to show our cyclical addiction to the endless beast better known as the mass media. Point in fact. She uses video artist Tom Sherman’s 1999 essay, “Before and After the I-Bomb,” as a sounding board. “Like the moth and the flame, we can’t resist this light,” he writes. “When we close our eyes or turn off our info-appliances, we still must mull over the afterimages, the disembodied voices, the imprinted sonic rhythms. We are eternally plugged in.” Norton, too, is eternally plugged in. But here, she uses it to master the art of tweaking and twisting the familiar quite ardently. For example, in Transfer Station, a 24- minute video, which loves to hate the mass media, MTV taunts, “Don’t even dream of touching that dial,” while a commercial break plasters a 1-800 number on the screen, urging you to give Corpus Christi a buzz, a Mother Teresa type who will help solve your problems for $3.99 a minute. How about a Jenn Norton fabrication, “Uncracked Crimes,” a show that spoofs on The X-Files, which always spotlights the unknown as dangerous and mysterious—but never cracks the code? Or Cherry Pop, a moppet-faced starlet whose trademark sound bite remains: “I’m Cherry Pop. Pop is short form for popular.” Everything here is about polishing that parody for popularity, no matter how vacant. While Transfer Station’s main narrative has Vladimir Kunst and Cherry Pop wrestling for the final spotlight like a sitcom special, the most intriguing part of this mélange of media satire is the army advertisement that carefully crafts mannerisms from American recruitment campaigns into a music video. “Join the army,” someone sings, calling to mind “America’s Army,” a global VR video game that trains freshly recruited youth into a series of soldier challenges, or what they dub as “immersing players in army culture.” “It’s hotter than ever before.”

Jenn Norton, Transfer Station, 007, video still, single-channel animation/video hybrid, 24:24 minutes.

But we know people hate the media. That is not new. Think of American journalist Chuck Klosterman’s 2003 essay, entitled “All I Know Is What I Read in the Papers,” which responds to the idea that there isn’t a secret agenda that dictates stories, but random circumstance, that the media machine is too bloated to manufacture consent and that “if talented writers honestly thought the world didn’t need to be changed, they’d take jobs in advertising that are half as difficult and three times as lucrative.” While Transfer Station is vivid, this hopscotch-paced, mercurial video—which crams in an abundance of cha-ching and canned laughter—succeeds in catching our attention and keeping it. Compared to Les Poupées russes, the other video in the show, it remains a sophisticated technical exercise in editing and animation with a predictable viewpoint.

Jenn Norton, Les Poupées Russes, 2007, two-channel video installation, loop.

In Les Poupées Norton looks past the pretty Pop and turns the lens inward. Silent and deadpan in approach, she stands in an empty studio with lights and camera—but no action. There is a continuous loop of the camera pointing out towards the audience, but it ends up picking up its own image in the mirror, recording itself. Looking for a way out, it remains trapped in an MC Escher-like looped maze of Norton as Cindy Sherman watching herself, which never ends. Without the Technicolor Pop world, she smiles self-consciously, trapped in a theoretical space that is not always comfortable, though it shows her in a truer light than we might expect. In both pieces one thing remains the same: both are counterparts to each other and fragments of a greater, unfinished whole. Norton has, no doubt, found a way to orchestrate another world hypnotically, but the challenge now lies in how she marries the inner and outer worlds. While looking inward makes for a few necessary revelations, delving into the melodramatic razzmatazz of Pop culture remains Norton’s true voice. Keeping it slick and sweet can, at times, tend to be a tad too saccharine, but she’s best when she’s sensational. It takes a critic to say so, even if they are puppet to their paycheque. ■

“Jenn Norton: The Insatiable Appetite of Russian Dolls” was exhibited at the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre in Guelph from September 5 to 30, 2007.

Nadja Sayej is a Toronto journalist.