Jenine Marsh

One of the determining factors of the global catastrophe we are living in is the wilful erasure of history to serve ideological ends. We arrogantly refuse to learn from the past; as we are doomed to repeat our errors and sins, the wreckage is piling up around us. Over the past several years, Jenine Marsh has forged a sculptural installation practice that has called to me like a blazon for its imaginative thinking about history and its weight through form.

A grounding structure for her recent work has been the fountain. Metaphorically rich, fountains have both the constancy of monuments and the ephemerality of flowing water. They are civic sites, often activated by the public through throwing in coins to make a wish, cementing the link between desire and money. A fountain’s ejaculations are utterly libidinal: they bring us pleasure and symbolize both the drive of coursing erotic energies and the liquidity of finance capital. no order, a 2023 installation for Joe Project in Montreal, saw Marsh pair a fountain with a leaning, constructivist-style wire tower displaying pages of the Communist Party of Canada’s newspaper, People’s Voice—often handed out at demonstrations or street corners—with salient phrases cut out. The newspaper, too, balances stalwart endurance with transience: a long tradition of critical Marxist thought is carried on fragile newsprint that often ends up blowing away in the wind or consigned to the rubbish bin. Marsh’s installation honoured the words she cut out and pasted, carrying ideas perhaps powerful enough to offer hope for surviving what she calls “end-stage capitalism.”

Jenine Marsh, Microcosm (Pyne, Bosch, More, close to shore), 2025, CP Rail trunks, hand-coloured decals, cardboard, faux gold foil, mod podge, trainpressed and altered mixed currency coins, plastic buckets, water, electric pumps, extension cords, portable power station, 535.94 × 93.98 × 71.12 centimetres. Photo: Nando Alvarez-Perez. Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole Gallery, Toronto.

Marsh pushed her fountain into a deconstructed state for her room-size piece at the Buffalo Institute of Contemporary Art (BICA) this past winter. We hear flowing water, but it remains hidden, a current of energy animating two rows of black buckets, which act as a support structure for a larger installation. Laid out on top like a raft or runway are three large metal trunks for train travel. Splayed open, the dissected cadavers have surprisingly shiny, reflective interiors, remnants of an era when the steam engine promised to close great distances and bring the far near. But this is more properly “emotional baggage” and, opened up this way, the golden-sheened trunks seem to contain only empty dreams.

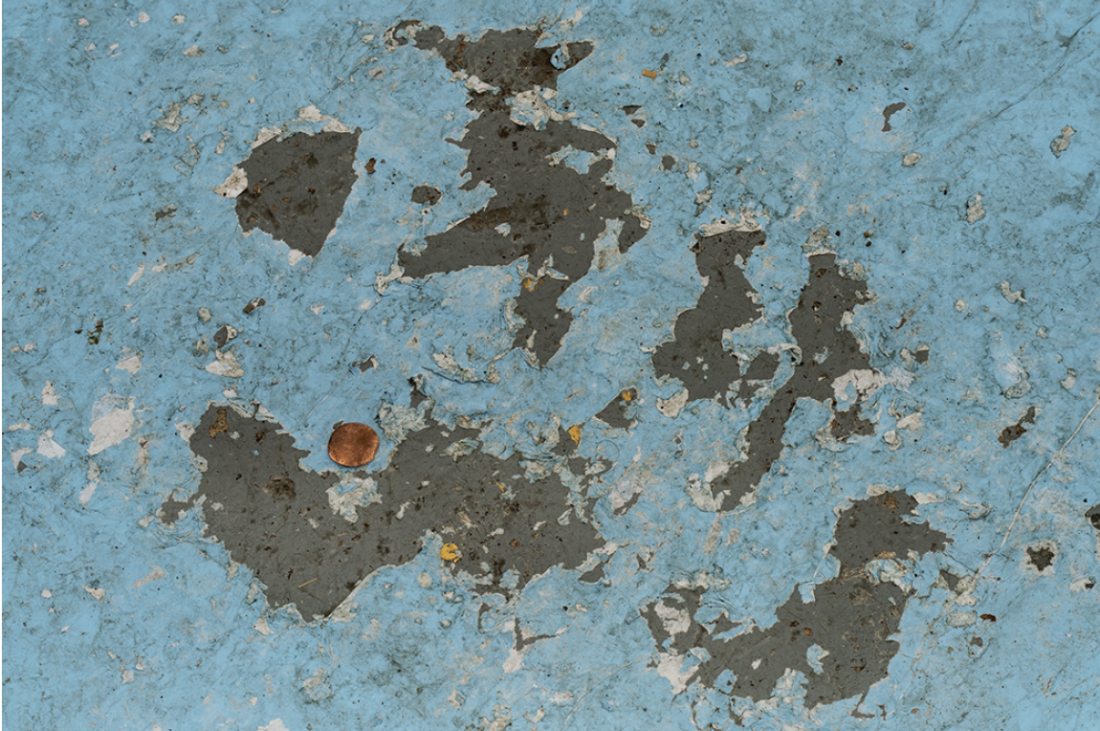

Appropriately, “Microcosm” played with scale. Walking into the once-industrial space, one is “at sea”—the floor is covered with a light blue paper the colour of a swimming pool bottom. What was once pristine and clean became scratched and soiled over the run of the show, with people’s footfalls indexed into it, creating all manner of rips and holes. Also embedded in the ground were mangled shopping receipts—the dopamine hit of the consumer purchase long receded. Ensconced in plastic and wired to battery packs so small lights could glow, Marsh’s familiar motif of flowers had their stems in water vials. If these are the show’s protagonists, their whole kit seems to mock the idea of individual autonomy and self-sufficiency. “Microcosm” also invited you to get down low to inspect the coins—another Marsh motif—balanced on the baseboard moulding around the space; they have been punched through, creating apertures, rendering them unusable for any transactions.

While the sound of the flowing water suggests fluidity and flight (“I wish I had a river / I could skate away on”), the staunch black buckets evoke our current state of emergency, suggesting acts like bailing out a punctured boat or catching water cascading from a leaky ceiling. The trunks, too, seem enormously bulky—once carted not by the bourgeois voyager but by a rail worker, historically a Black porter—looking more like the remnants of heavy machinery, or even mysterious fragments of the train itself, than accessories of leisure travel.

Jenine Marsh, installation view, “Jenine March: Microcosm” (detail of floor), 2025, Buffalo Institute of Contemporary Art, Buffalo. Photo: Nando Alvarez-Perez. Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole Gallery, Toronto.

On the trunks, alongside the Canadian Pacific address labels that slowly peeled away with time, were images depicting simple scenes of manual labour. The artist’s statement explains that an 1808 manual titled Microcosm of London “was designed for house-bound bourgeois women to help them imagine and depict the daily lives and labour of the working class. From the protective utopia of the country estate or city mansion, these hobby artists drew and painted images of another utopia: a quasi-real world of fresh air, open spaces, and a purposeful life of work.” Transferring these vignettes, which repeat to show their generic function, onto the luggage conveys the rigid separation of the classes, a gap that is inevitably filled by fantasy. The dignity and value of the sawing, threshing, ploughing and washing shown in the illustrations are clear but what about that of artmaking?

All the libidinal feeling that might be contained in the flowing fountain, in holiday travel, in artmaking and in class fantasies is sublimated into another element of the installation, which replicates one of the most transgressive libidinal landscapes in art history. On one wall hangs a clear Plexi box encasing a small jigsaw puzzle version of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1500, which, notably, has a fountain as its centre. While its central panel writhes with frenetic, polymorphously perverse commingling, the Eden and Last Judgment side panels of the triptych have been quietly reversed here in Buffalo, far from the painting’s home in Madrid. The box contains coin slots on the sides to receive donations (and perhaps wishes) from visitors, the currency accumulating at the bottom. Circular discs have been cut out of the puzzle, the roundels with fragments of the Flemish painting’s delirious transgressions transferred to be sprinkled like seasoning on the trunks. The empty circles left in the puzzle have been replaced—or, rather, exchanged—with coins that have been flattened on train tracks. The force of flowing water thus converges with the force of a train. Both heavy and light, “Microcosm” asks us to consider the solidity of what seems to be unchangeable and the transience of what seems to be fleeting.

The gallery refers to “histories of aspiration and failure,” and these utopian dreams past are palpable in Marsh’s own labours and hopes. Her work is not camp, but it is resolutely anti-monumental; the cheap and disposable (or already disposed of) are loaded with a burden of meaning beyond what they should be able to bear. Made from humble parts, “Microcosm” doesn’t seek to transcend its materials, yet somehow maintains the capacity to dream. ❚

“Jenine Marsh: Microcosm” was exhibited at the Buffalo Institute of Contemporary Art, from January 24, 2025, to March 29, 2025.

Jon Davies is a curator, writer and art historian from Montreal. He received his PhD in art history from Stanford University in 2023. He was the 2024–25 General Idea Fellow at the National Gallery of Canada and from 2025 to 2027 will be a SSHRC post-doctoral fellow in the history department at Carleton University.