Jeff Wall

Spanning 30 years, the astute selections in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Jeff Wall” retrospective observed a loose chronology and looser affinities. Wall produces his signature full-colour transparencies, housed in enormous light boxes, at the rate of only three or four per year, the ruminative pace expressed in meticulous attention to detail. Lit from within, the dense tableaux appear to float, the effect open-ended, a question posed rather than answered. Especially in the later work (including several pared-down still lifes in a concurrent show at Marian Goodman Gallery), Wall undermines the trust in photography as evidence or narrative. Even when he makes his allusions clear, as in A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993, a reprise of Hokusai’s A High Wind in Yeijiri, 1831–33,—minus Mount Fuji—or After “Spring Snow” by Yukio Mishima, Chapter 34, 2000–05, a claustrophobically precise rendition of an adulterous Japanese wife in the cabin of her 1912 Model T as she tips incriminatory sand from her shoe, Wall avoids conclusive meaning. His photographs don’t tell, they show, exploiting surfaces in and of themselves, to which photography is particularly suited.

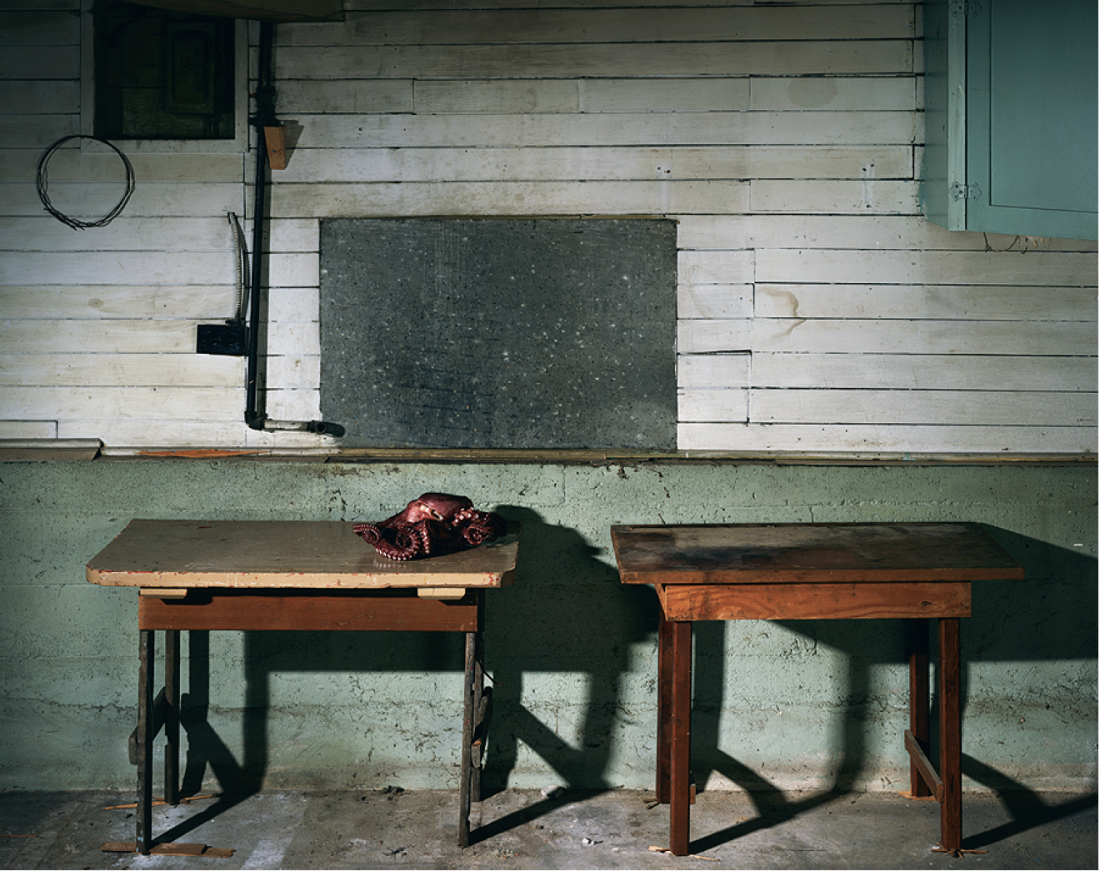

Jeff Wall, An Octopus, 1990, silver dye bleach transparency in light box, 71 5/8 x 7’ 6 3/16”. Private collection. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Zürich. Photographs courtesy MoMA, New York.

Born in 1946, Wall took a circuitous route through painting, to photo-texts (one of which was included in MoMA’s landmark Conceptualism show, “Information,” in 1970), and then a break from art making to study at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, culminating in a brief excursion into filmmaking. Though the collaborative process didn’t suit him, the props and scene making did. He experimented with staged images, eager to recreate the sweep and scale of Velázquez, Goya or Titian. He chanced upon his method, when, fresh from a visit to Madrid’s Museo del Prado in the late 1970s, the backlit advertisement at a Spanish bus stop popped out at him.

In Picture for Women, 1979, he jiggered the elements of Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, and set them in a photographer’s studio. To the left, a skeptical young woman meets the viewer’s gaze and, on the right, Wall himself keeps wary watch. Between them is a big-view camera trained on the viewer. A response as much to Manet as to feminist and Marxist criticism of the time, Picture for Women is also a frank acknowledgement of the artifice of Wall’s practice and the centrality of photography itself to his project. From the outset and through to the present, Wall’s work has been investigative, his photographs an ongoing inquiry into what photography can do.

Jeff Wall, In front of a nightclub, 2006, silver dye bleach transparency in light box, 7’ 5” x 10’ 1/16”. Collection: Pilara Family Foundation; promised gift to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In Mimic, 1982, a Caucasian man, girlfriend seemingly in unwilling tow, gesturally insults a bypassing Asian man, or in An Eviction, 1988, reworked in 2004, an overhead view in which minuscule players are overwhelmed by the housing development they’re forced to leave, Wall uses neo-realist techniques to incorporate social realities. Later work— such as In front of a nightclub, 2006, in which, amid the young denizens, a flower seller moves beneath the surveillance camera’s watchful eye, or Overpass, 2001, where four people, burdened with luggage, their backs to the camera, walk through an industrial area—alludes similarly to social problems without documenting them. Like the neorealists, who, in André Bazin’s formulation, used “fact” to produce “reconstituted reportage,” Wall’s pieces extract incidents from ordinary life, echoing the tension and exaggeration of an exchange remembered, rather than witnessed.

Each of these images has physically difficult if not impossible perspectives, drawing attention to the actual technology involved in making the work. Initially composites of multiple shots, Wall’s recent pieces rely on Photoshop and other digital techniques as much as actual shooting. His keen, finicky attention to details such as the tufts of grass that infiltrate sidewalks and walls, the tiny bits of urban litter no city escapes, or the sheer clutter in which the two young women live in A view from an apartment, 2004–05, give his tableaux the filmic quality of a long take: they create an atmosphere too congested to absorb in one go, the impression of action holding its breath.

Jeff Wall, A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993, silver dye bleach transparency in light box, 7’ 3 3/16” x 12’ 4 7/16”. Tate, London. Purchased with the assistance of the Patrons of New Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation and from the National Collections Fund.

The light boxes heighten the movie-screen effect, but in recent, equally large, gelatin silver prints, Wall achieves a parallel, monumental effect even absent the neon, and in black and white. Of particular note was Night, 2001, a nocturnal view of a homeless couple encamped along the edge of a pond near an overpass. The stagnant, creepy water reflects the highway struts, the overpass, the spotty vegetation, but not the people, on whom it seems to encroach. The multiple viewings needed to make the image reveal itself give it a certain movement, reminiscent of filmmaker Béla Tarr’s extended shots, with a similar exploitation of charcoal grey and velutinous black.

Wall has steadily worked towards a refracted reality, producing images that have a looking-glass quality, as if his final tableau is merely a reflection, the source unavailable. This expresses itself at a surreal level in The Flooded Grave, 1998–2000, with crows straight out of Hitchcock’s The Birds dotting the grounds and sky above a cemetery, an open grave tide-pooled with urchins, starfish and seaweed. The minutiae—an orange hose in the background, two tiny, retreating gravediggers in yellow, a large Christmas tree pine in the middle distance—are like the seemingly unimportant details on which memory fixes. But, like the other pieces, this isn’t memoir but memory filtered through technology; not evidence of what did happen, but of what photography makes happen. ■

“Jeff Wall,” a retrospective exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from February 25 to May 14, 2007. It will then travel to the Art Institute of Chicago, where it will be exhibited from June 30 to September 23, 2007, and then to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from October 27, 2007, to January 27, 2008.

Megan Ratner is a regular contributor to frieze and Art on Paper, and is Associate Editor at Bright Lights Film Journal.