Jeff Koons

There are many official reasons why “Jeff Koons: A Retrospective” was significant. The exhibition of almost 150 objects spanning three decades of production was Koons’s first retrospective in New York and the 80-some year-old Whitney Museum’s largest survey of a single artist. As the Whitney’s closing hymn on Madison Avenue, the retrospective also marked the end of an era and new beginnings for a prized cultural institution. They will be turning over the keys of the Marcel Breuer landmark building in a leasing agreement with the Metropolitan Museum of Art before assuming new Renzo Piano-designed digs in the fashionable Meatpacking District in 2015.

But the official story is not the whole story. We’re talking about Jeff Koons, an artist for whom any institutional sanction must be measured against the ire that his ostentatious production costs and unrelenting tributes to kitsch, porn and infantile pleasure routinely inspires—an ire that seems to grow in direct proportion to the astronomical prices the artist’s works command in the market. I won’t say the Hungarian-Canadian performance artist Istvan Kantor’s unanticipated blood “donation” at the Koons show in August was an expression of this ire necessarily, but it certainly served as a reminder that Koons is to controversy as light is to a moth.

In an early review of the retrospective, critic Jerry Saltz (not a hater, exactly) provided a nice encapsulation of the underlying judgment that fuels the rancour: “The rich and greedy buy [Koons’s art] because it lauds them for their greediness, their wealth, power, terrible taste, and bad values.” But it’s not just that by taking Koons seriously you are somehow in league with the Wolves of Wall Street; doing so amounts to intellectual disgrace, accepting “lobotomy by art,” according to Christian Viveros-Fauné of the Village Voice.

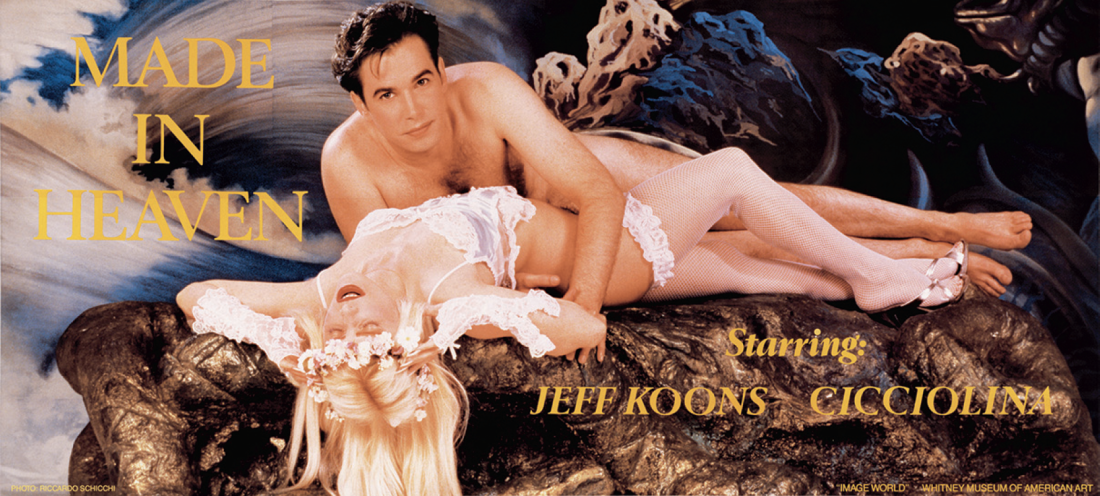

Jeff Koons, Made in Heaven, 1989, lithograph on paper on canvas, 125 x 272 inches. Artist Rooms Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland. Acquired jointly through The d’Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and Art Fund 2008. © Jeff Koons. Images Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

For his admirers, Koons is the legitimate heir apparent to American Pop. In step with the late Dalí and Warhol, his art celebrates surface as the site of truth and transcendence through immanence. He has always relished this apparent paradox without irony, “blurring the line between innocence and prurience,” as the exhibition’s curator, Scott Rothkopf, once observed, with the aim to recalibrate a value system that equates surface with superficiality. As the Whitney’s website explained (implored?), Koons simply wants to “liberate” audiences “from the stigma of bad taste.”

Occupying five floors, the otherwise largely chronological display began with Koons’s most recent series. “Gazing Ball” consisted of full-scale replicas of iconic Greco-Roman sculptures, alongside a mailbox decked-out to resemble a hot-rod engine (a popular folk object in rural America), each rendered in flawless white plaster and mounted with a reflective orb of blue glass—a popular lawn ornament Koons recalled from his youth in Pennsylvania. And so with this double-barrelled ode to Classical antiquity and blue-balled Americana, the pure and the profane together began their untroubled bottomless freefall.

The exhibition continued on the second floor with Koons’s earliest works. The cheap inflatable rabbits and flowers displayed against mirrors, the encased and untouched vacuum cleaners lit by fluorescents, the basketballs suspended in aquariums like commercial relics—shiny on the outside, empty on the inside—perfectly articulate the eclipse of depth by surface. In the mid-1980s, Koons turned from found pneumatics to billboard-sized reproductions of liquor ads on canvas and to tchotchkes cast in the commonplace but visually seductive material of stainless steel. His new direction turned on issues of class identity, consumption and what he called expressions of “proletarian luxury.” That decade witnessed Koons abandon the readymade (creating art from crap) for re-fabrication (transforming crap into art); broadly speaking, Dada for Pop.

Jeff Koons, Poodle, 1991, polychromed wood, 23 x 39.5 x 20.5 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Promised gift of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner P. 2011.212. © Jeff Koons.

By the 1990s, the artist was ready to take the idea of surface to its metaphorical extreme, and he turned to pornography. For his salacious “Made in Heaven” series Koons himself appeared in his sculptures and, most memorably, huge florid vignettes documenting his various sexual exploits with the Hungarian-Italian porn star and politician Ilona Staller, who later became his wife. Whether or not this project of hedonic excess helped Koons exorcise his sexual shame, as he claimed, it’s not hard to construe the series as the historical culmination of a profoundly chauvinistic strand within American Pop. The series represents a bold reclamation of male heterosexual identity and desire, of a virile pride that supervenes on the semiotics of female sexual participation, complicity and acquiescence. “Made in Heaven” is deeply problematic, offensive; but it also remains a terribly important object lesson, foregrounding (whether intentionally or not) the issue of gender inequality in our so-called post-feminist era.

If a deep affection for kitsch came to represent one well sharpened edge of Koons’s early practice, by the 1990s he had turned equal attention to the other side of the blade: the aura of craftsmanship. The perverse merger of kitsch and craftsmanship reached nauseating perfection in the “Banality” series: an entourage of multi-figured sculptures sourced from stuffed animals, Renaissance painting and everything in between, exquisitely rendered in porcelain and polychromed wood by recruited German and Italian church artisans. Arranged by Rothkopf as if enduring a police lineup, the works ran the gamut from the impious to cloying monstrosity, and included the famous pieta of Michael Jackson with Bubbles the chimp.

Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog (Yellow), 1994–2000, mirror-polished stainless steel with transparent colour coating, 121 x 143 x 45 inches. Private Collection. © Jeff Koons.

It’s worth noting that by the 1990s Koons’s personal life was far from banal. In just over five years, he had married, divorced and entered into a lengthy custody battle with his “Made in Heaven” co-star, who had absconded with their son to Italy. While this might have inspired pause in a lesser artist, without missing a beat Koons simply started making art about childhood innocence. Indeed, the various series he has advanced in the last decade—barring “Gazing Ball”—combine a visual cacophony of giggles and coos with a heavy dose of engineering genius and technical outsourcing: massive and exactingly rendered paintings of cartoon characters, plastic toys and confectionary, everything culminating in a mountainous turd of Play-Doh rendered in multicoloured aluminium and a massive chromed stainless steel balloon dog, which Koons tellingly refers to as his Trojan horse.

Koons may be extravagantly successful, but he is also easy to criticize. Too easy. Indeed, criticism of Koons invariably ends up pooling around verdicts of superficiality, banality, stupidity, and this only confirms the artist’s overarching commitment to surface-as-depth. He has played his version of Pascal’s wager nicely: either audiences will love his work or they won’t; but, if they don’t, it will be for all the right reasons. I imagine “Jeff Koons: A Retrospective” will accomplish what any Koons exhibition sets out to do: bring in the prestige and the cash with the controversy. That it was the target of agitprop protest only confirms Koons’s brand. So long as those who loathe the man and his art continue to do so with a bottomless reserve, Koons will remain a favourite of mega-collectors and a Venus flytrap for critics who want to luxuriate in righteous indignation. ❚

“Jeff Koons: A Retrospective” was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, from June 27 to October 19, 2014.

Andrew Kear is Curator of Historical Canadian Art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.