Jean-Francois Lauda

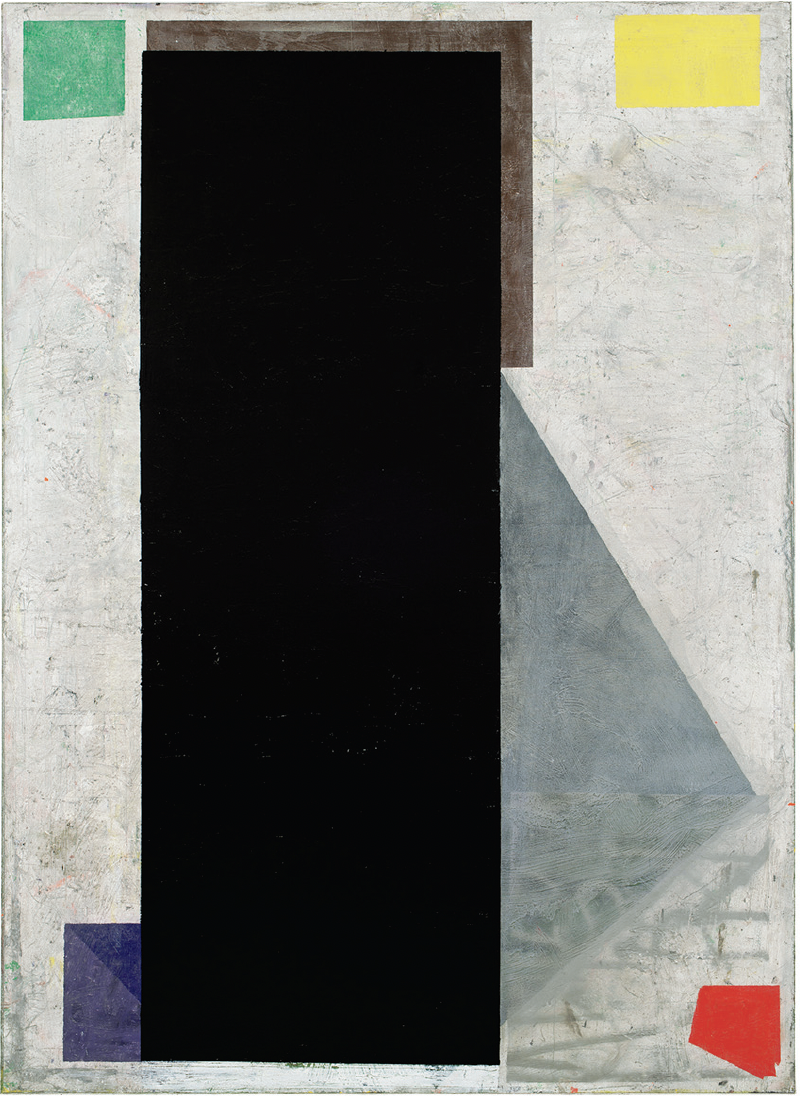

Jean-François Lauda, B.23, oil on canvas, 2013, 72 x 52 inches. Courtesy the artist and Battat Contemporary. Photograph: Éliane Excoffier.

Jean-Francois Lauda is a chameleon painter. On one hand, he is a resolute abstractionist whose work often yields fugitive echoes of earlier abstractionists (the constructivists, Richard Diebenkorn et al, yet always in generic rather than specific fashion) and, on the other, a wily scavenger who often works from a latter-day disconnect with existing traditions through the use of found templates and the incorporation of a radiant “grunge” factor distinctly his own. But he is no formalist. To label him such is to make a category mistake. He has forsaken all the formalist orthodoxies and archaic ideals of abstract lineages in order to secure his own truth. His feral scavenging dovetails with his profoundly improvisatory, intuitive and anarchistic sensibility. He embraces imprecision, chaos and chance incident as working principles.

American painter Thomas Nozkowski (b. 1944) once said that he never uses tape or rulers to draw his lines because he believes that painters should work to their “level of performance.” Lauda, through radical indeterminacy and determined imprecision, makes paintings that are at once seductive and subversive and uses tape and template when he deems necessary. Yet he does so not all the time and not in any prescriptive way. Still, he works to his “level of performance.” He does not rely on a stocklist, an inventory of inherited formalist tropes. And he can’t seem to make a bad painting, probably because before a given painting crosses the finish line he finesses it, tweaks it and ensures it works as a well-crafted, if not exactly formal, whole. But his methodology is highly anarchist and idiosyncratic in its mien. He refuses free passage from utopian signifier to painted thing.

Lauda is also a prolific musician and sound artist, and days and nights in his studio are spent jumping from making music to painting. There is cross-pollination in this collision that is also intertwining. In painting, he flirts with loss of control in order to achieve fulfilling accidents. This tension between chaos and control deeply informs his art. He installs insecurity in what is, at base, a sort of painterly bricolage fraught with rhythms and rhymes.

It is interesting to note that Lauda represents the fourth generation of artists in his family. His great grandfather was an architect. His grandfather was an artist and a graphic designer for the CBC who also executed many works of public art. His father was a noted artist. Lauda salvaged scores of coloured cardboard from his grandfather’s studio and often uses them as found templates for forms in these paintings. He has been around art his entire life.

His working methodology is interesting. Using the salvaged cutouts appealed to him because they were already there. Presumably, this appealed as well to his desire to remove himself from the work in terms of tools of facture, in a strange way recalling what Jasper Johns argued for in his earlier work, namely, that he attempted to develop his thinking in such a way that the work he did was not him. Johns did not want, at least in his earlier work, to expose his own feelings. In order to introduce unforeseen and “chance” elements and avoid anything formulaic, Lauda often interposes impedimenta between himself and his work. And yet, herein lies the paradox: his work is flooded with auratic feelings that seep out of his canvasses like groundwater. Thus, the works at Battat generated the volumetric mood of an environmental installation.

If you look closely at the fragmented geometries in his paintings, they are seldom hard-edge but minutely bevelled or subtly crenellated. This shadow abstraction with its ghost traces of previous incarnations and sundry erasures demonstrates his loose, unfettered and textural capabilities.

Lauda hews to Philip Guston’s course as a painter who finds in anxiety a sort of freedom. He sees the logic and necessity of Guston’s acquiescence to what he called the “third hand,” the hand that works the canvas in ways outside his conscious control. He also covets stumbling, when stumbling shows him the way forward, not the road back. This is why he respects and works with third-hand interventions, embracing the indeterminate as a means of breaking through blockage and repetition. His emulation of Guston’s mindful angst helps grow his art outside all expectations and orthodoxies.

He builds his surfaces slowly, like intricate spiderweb scaffolding. Using the cardboard cut-outs, for example, he will lay down the outline of a form that is then painted in with declarative intensity. The colour is like a hot cinnamon sunset. He will use this outlined geometry as a sort of protractor, plumb bob, and then introduce something proximate that accretes structural sense. He fine-tunes his way towards the threshold with multiple erasures, traces and superimpositions rife with tonalities. Small imperfections sound grace notes in the scaffolding of a given painting as he spontaneously builds towards conflation. He trims down as he reaches the threshold when the painting is more or less complete. His erasures open tiny windows on several undercoats, and these read as a hectic illumination of a work’s processual history and memories of anterior light. There is a grunge factor too in this painting—Lauda does not disdain the dirt a painting accumulates as it comes into being—that redeems it from any semblance of formalist purity.

Despite its seductive palette, perilous geometry and profound melodism, Lauda’s art is pared down and feeds on itself, but this happy auto-cannibalism is less Jean McEwen at his height (a quintessential Scot, McEwen would often paint over his old masterpieces rather than buy new stretchers and this tendency brought tears to my eyes on many of my visits to his studio) than Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son, which depicts the Greek myth of the Titan Cronus (romanized to Saturn) who, fearing that he would be overthrown by one of his own children, ate each one of them as they were born.

Again, it’s worth repeating that the furtive whispers of other and earlier abstractionists found here are only that: whispers from the wings of painting without open quotes. If you think of hoary plasticien ideals here in Quebec, Lauda eschews tired old ideals in favour of edgy, ongoing and experimental invention. The great strength of this work is its thematic consistency, even as it remains resoundingly anarchistic, not in debt to anything that came before. ❚

“Jean-François Lauda” was exhibited at Battat Contemporary, Montreal, from September 19 to October 26, 2013.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator living in Montreal who contributes regularly to Border Crossings.