Jasper Johns

We move into the world and there is a trace left behind, things have been affected and marked, evidence left by our passing. In the mid-’50s, when Jasper Johns thought of painting a flag, the art world was engaged in the bravado of the gesture; Abstract Expressionism was in full swing and its influence was global. Johns, a young artist in New York, took a radical step. Moving sideways, he chose to make an object, not to paint a painting.

“Jasper Johns: Gray” is a remarkable exhibition organized by the Art Institute of Chicago in collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Following on last year’s survey at the National Gallery in Washington, entitled “Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting 1955–65,” this exhibition focuses on the many permutations of grey the artist had used since the mid-’50s. Featuring 119 paintings, prints, drawing and sculptures, the exhibition gives us an entire overview of the ideas that have preoccupied Johns for five decades.

Jasper Johns, Target, 1958, sculp-metal and collage on canvas, 12 x 11”. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts. © Jasper Johns/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Jamie M. Stukenberg/ Professional Graphics Inc., Rockford, Illinois.

Beginning with the flags, targets and maps, Johns set out to claim painting as a record of engagement. More than the products of the so-called “action painters,” the target and flag works captured the idea of time; they didn’t fall into the easy trap of thinking a gesture could stand as the record of an action. Johns’s mark making acted more like the grooves cut into the surface of a vinyl album, each mark being a moment and each object an accumulation representing a continuum. I get the sense that you could almost put one of his targets on a turntable and play it to hear how he spent that particular period of time in his life.

The subject matter was deliberately banal; at the same time, so meaningful it was meaningless. This was a strategy that stabilized the object, fixing it in one place while the artist worked on the surface. A target is a target is a target. It is nothing else. Johns collaged newspaper clippings onto the surfaces of his canvases, often using them to delineate the design, then he worked back overtop with encaustic paint, a material made with beeswax. The instantly dry surface suited his needs and instilled a dull matter-of-factness in the quality of the surfaces. The greys he used were rarely just grey. He put layers over bits of colour and mixed in warm hues so that the greyness took on subtle tones, being every colour and no colour at once. I think of Johns as a draughtsman of ideas, the first conceptual artist. To work in grey was for him a pragmatic choice and a logical one. His paintings weren’t out to entertain, they were there to simply be there. To displace air, take up space, confer significance on everything but themselves.

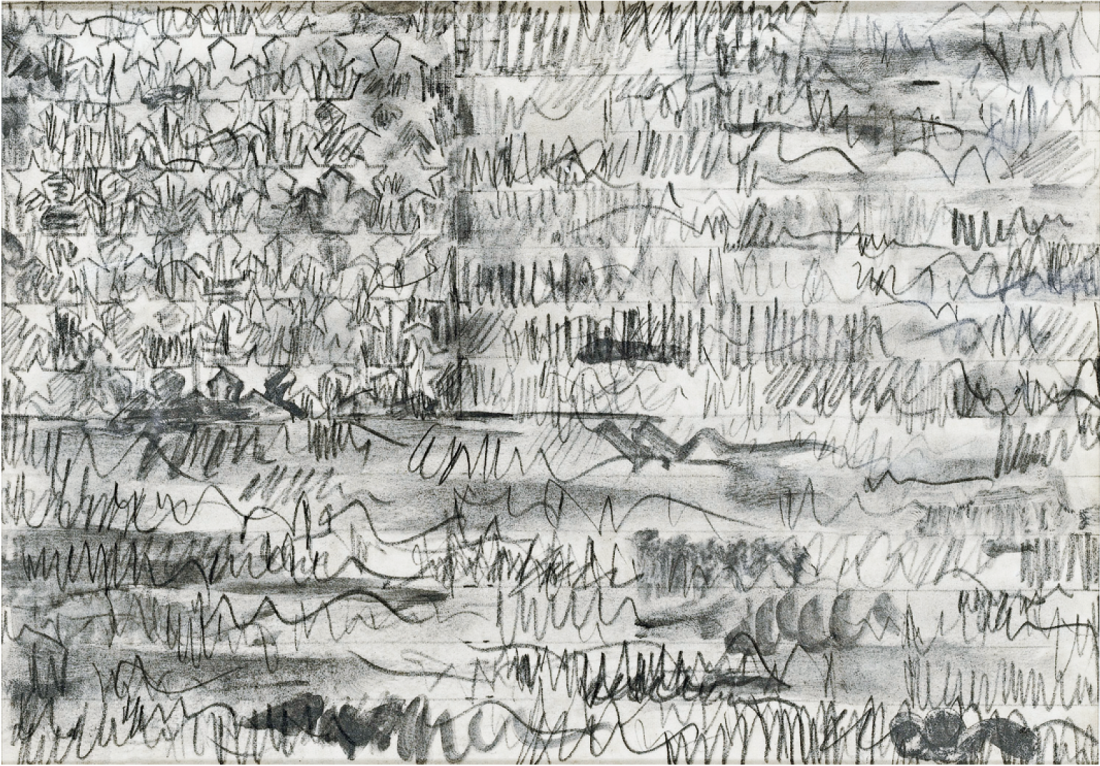

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1958, pencil and graphite wash on paper, 8 7/8 x 12”. Collection of Barbara Bertozzi Castelli. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Jamie M. Stukenberg/Professional Graphics Inc., Rockford, Illinois.

Standing in front of the small, 12 by 12-inch grey target from 1958, I got a glimpse into a moment. It’s a modest work that is as powerful as if it were 12 by 12 feet. The buildup of brush strokes is like the individual tics and tocs of a clock. I was born that year and I wonder if that target recorded a moment near my birth.

The catalogue contains a revealing interview with the artist. While the interviewer tries to make something of his working methods, Johns keeps bringing everything back to the simple choices an artist makes in his studio. When asked, “Do you think of gray as a positive color?” he replies, “Yes, I think so. I don’t know, I don’t really often think about gray. I mean, I work with it, and I guess that’s a form of thought, but I don’t have particular ideas about it that can be separated from the work.” For Johns, decisions come in the passing of time and the most pragmatic way to lay down experience. When describing Near the Lagoon, 2002–03, for example, he simply says, “The painting is largely made of things put down on other things.” His way of working was as matter-of-fact as the way the finished pieces presented themselves.

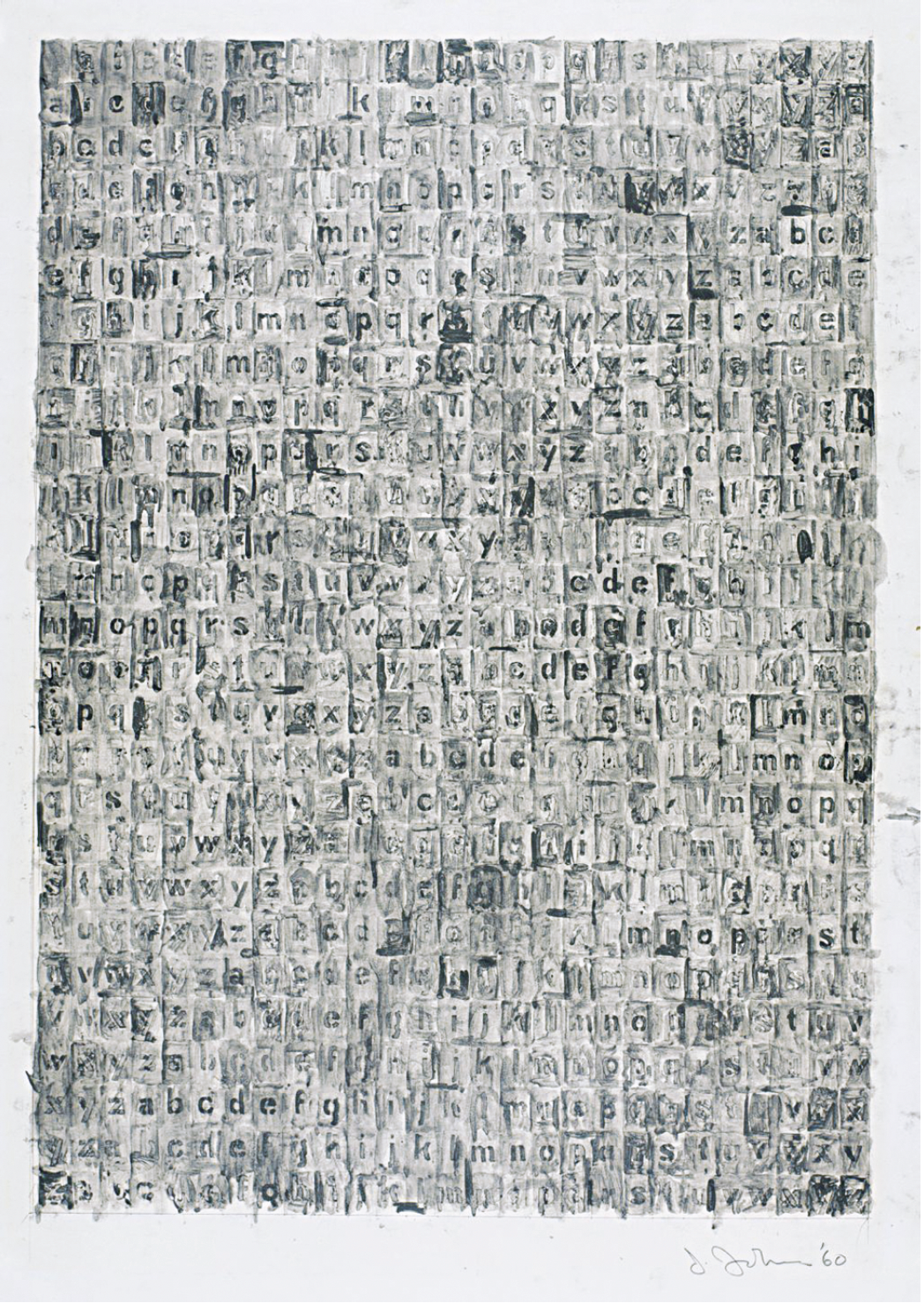

Jasper Johns, Gray Alphabets, 1960, graphite wash on paper, 38 3/8 x 27 7/8”. Collection of Jean-Christophe Castelli. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Jamie M. Stukenberg/ Professional Graphics Inc., Rockford, Illinois.

One discovery for me was a small work about 9 by 6 inches entitled Painting Bitten by a Man, 1961. This is a panel of wax that the artist has literally taken a bite out of, creating an impression in the centre. This is what Jasper Johns did to the history of painting: he took a bite out of it, changing what art was going to be about. The object from that point on became front and centre, leading to, for example, the paintings of Frank Stella, the minimalist sculptures of Robert Morris, the conceptual works of Lawrence Weiner and, later, the objects of Sherrie Levine. Johns continues to be a working artist whose recent output, also included in this exhibition, is as interesting as his early work, and I believe will prove to be as vital. ■

“Jasper Johns: Gray” was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from February 5 to May 4, 2008.

Randall Anderson is an artist and writer living in Montreal.