Jason McLean

The opening of “Son of a Salesman” at Michael Gibson Gallery is not an ode to Biff or Harold Loman, the unfortunate sons of Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s seminal play Death of a Salesman. As is often the case with London, Ontario-born artist and off-hours autograph hound Jason Mclean, it must be assumed that his titles, like the subject matter of his work, are drawn from intimate moments in his own life. McLean’s vernacular is the origin of his alchemy, the complicated soup of his aesthetics; and true to the title of the exhibition, McLean’s father was a salesman, a car salesman in fact. Call it what you wish—autobiographical, self-referential or personal narrative—McLean is a mapper of memory, a cartographer of the everyday, an archivist of minutiae, a chronicler of the prosaic. His work remains devoted to this reflexive methodology in many ways and has for many years, wherein events from his life continue to drive the idiosyncratic visual vocabulary that is instantly “McLean.”

Of course, it’s not all fun and games; McLean’s work rarely appears to rest easy on the wall. An underlying sense of anxiety festers in both text and image-based works, where direct references to mental illness, emotional pain, threats of isolation and financial concerns sit and smoulder. In “Son of a Salesman,” themes of displacement, migration and uncertainty pop up in the abstract geometry and interplay of his forms. As such, they are wholly representative of the artist’s move to Brooklyn, New York in 2014. It speaks directly to the obstacles of making home in a far louder, faster and larger city than that of London, ON, the ZIP code of some of McLean’s art heroes like Jack Chambers, Greg Curnoe and Paterson Ewen. Moving south of the border to NYC reflects the artist’s desire, since boyhood, to make it big in the art world’s unofficial Mecca; no longer a mid-career Canadian artist, he’s a mid-career Canadian artist living in the United States. There’s a difference.

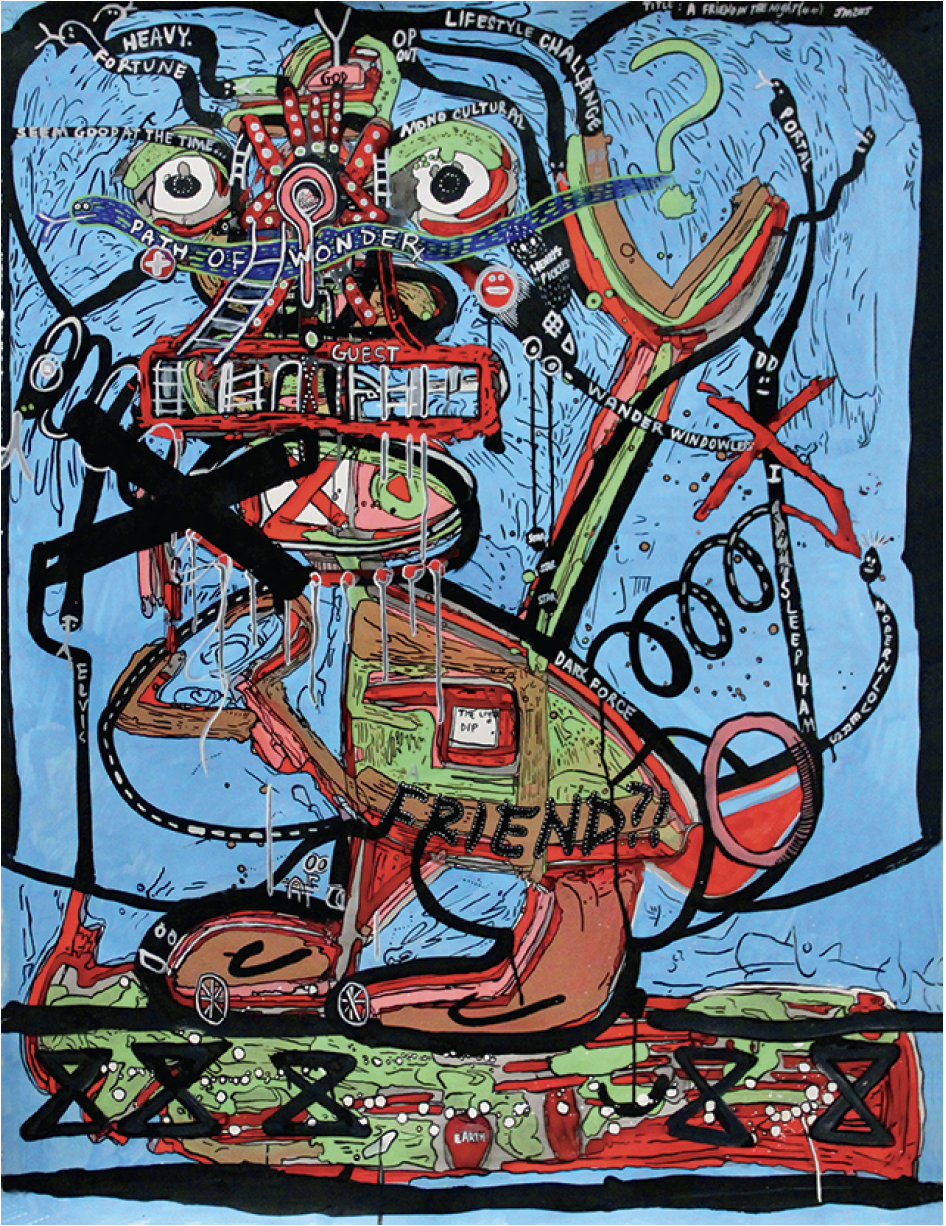

Jason McLean, A Friend in the Night (M.M.), 2015, acrylic ink on paper, 50 x 38.5 inches. Courtesy Michael Gibson Gallery, London, ON.

Consequently, McLean’s work is beginning to expand internationally as he is now represented by Wilding Cran Gallery in Los Angeles, and he was recently included in the exhibition “Please Enter” at Franklin Parrasch Gallery in New York, curated by glam collector Beth Rudin Dewoody. It should come as no surprise then that McLean’s signature aesthetic confronts the challenges associated with the 49th parallel and his big move. Take, for example, the subdued ink on paper BFSP, 2015, a cheeky acronym for “big fish small pond.” Here the word “London” is appropriated to read “Pondon,” while the text hovers over a shallow blue pond that doubles as the top of an hourglass. “NY” and “LO,” acronyms for New York and London, feed off the “Pondon” header while the grains of sand accumulate at the bottom of the hourglass; in other words, his time in London is up. It’s a revealing work in that it mirrors the artist’s mounting frustration over being underappreciated in the Canadian art world while the phone rings from galleries in the US and Europe. Elsewhere, in works such as Do Not Bend, 2015, tropes surrounding success and rejection rest heavy and loom large while spilling into other, more nonsensical equations and symbols that are sourced from McLean’s daily material. What viewers encounter are the threads of scepticism relating to profession and cultural legacy; a drama of inner conflicts captured, recorded and playing out in real time.

In these new works, his use of line and colour has tightened and now pushes to the edges of the paper; this “all-over” composition in works such as A Friend in the Night (M. M.), 2015, represents a subtle nod and wink to the graffiti art and urban grit of Brooklyn’s silver streetscapes. There is also evidence of an intense reworking of pen and pigment, which uncovers a fierce process-driven appetite to get it just right. Other works include typically Big Apple tropes: David Letterman is in there with Letterman’s Done, 2015, so too is Keith Haring in Slow Drip Needed, 2015; in fact, McLean’s preoccupation with autograph hunting in his extensive collection of Pez dispensers (part of the nomadic Felix and Henry’s Canadian Pez Museum, named after his two sons) saw the artist frequent television studios, exhibition openings and music shows. It’s odd that critics overlook McLean’s murmurs of Dadaist absurdity witnessed through his intense preoccupation with the cult of celebrity both in his collection activities and his professional practice. For further proof see the opening for “Son of a Salesman,” where artist and writer, “The Canadian Romantic,” Robert Dayton delivered a bare-chested monologue performance clad in glitter with slicked-back hair hilariously trolling the packed audience with campy social commentary. Later in the night McLean handed out Oh Henry! chocolate bars on a silver platter—a friendly quip on his son’s name—while wearing a vintage Gibson guitar T-shirt, a sly promotion of his patient gallerist Michael Gibson; it’s everything Dada, and a bit of fun to boot. The result is a daft paradox of merrymaking set against a handful of works dotted with real threats of plight and pathos. So be it. This son of a salesman has big dreams. ❚

Jason McLean, Letterman’s Done, 2015, acrylic ink on paper, 42 x 63 inches. Courtesy Michael Gibson Gallery, London, ON.

“Son of a Salesman” was exhibited at Michael Gibson Gallery, London, ON, from November 6 to November 28, 2015.

Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD, is a curator, writer and educator based in London, ON. His writings have appeared in numerous Canadian and international art publications including Canadian Art Magazine, First American Art Magazine and FUSE Magazine.