Jason McLean

Vancouver is home to a diverse and intensely dedicated community of artists whose primary focus is making art on paper. This group includes people like Marc Bell and Mark Delong, Amy Lockart, the artist collective Lions, Igor Santizo, Shayne Ehman, Shay Semple and Jeff Halliday, Sonja Ahlers, Jeff Ladouceur and Julie Morstad, Eli Boronowsky and Nicholas Pittman, and many, many talented others, aware of and collaborating with each other in no particular order. But among this large and unclassifiable group, whose work spans a range from cartoon weirdness to pure abstraction, Jason McLean might be the city’s leading practitioner and simultaneously the most far out. What defines McLean’s work more than any surface, style or scale is the flow. You’re drawn to it for what his hands, his eyes and his mind can pull off. In his mastery of form and formlessness within each and every line, McLean has no equal.

Jason McLean, Ovaltine Café, 2006, acrylic paint / carving on 78 record player with motor, ceramics, hat and hat box, 54 x 18 x 22”. Images courtesy the artist.

In the window of the Tracey Lawrence Gallery was a vintage white fridge next to a black welcome sign that read almost legibly: “back in 5 min.,” the name of McLean’s most recent show there. The fridge, an old Studebaker-style with vehicular curves, is snarled in a webby coating of black and blue ink, a mire of McLean’s free-jazz graffiti, including word games à la Gertrude Stein, dangly filaments and squiggly humanoids, and this fridge was stocked with O’Douls non-alcoholic beer cans with their bottoms cut out to make them into patio lanterns, fully illuminated with those pill-sized multicoloured Christmas lights. McLean’s appreciation for non-alcoholic beer is a funny and salient tangent on a recurring subject in his work— mental health. In addition to the names of major pharmaceutical brands popping up on the faces of 19th-century gentlemen, on golf courses and over road maps, there are the many language references to the paranoid late-night radio show Coast to Coast, hosted less and less frequently by the sonically Oz-like Art Bell, not to mention the overall air of mystifying psychedelia that intensifies the skull trembles when you look at McLean’s drawings, where faces and figures will appear as solid masses on a landscape in the same eyeful as the entire composition melts to liquid, acrylic ink on paper, flat as that.

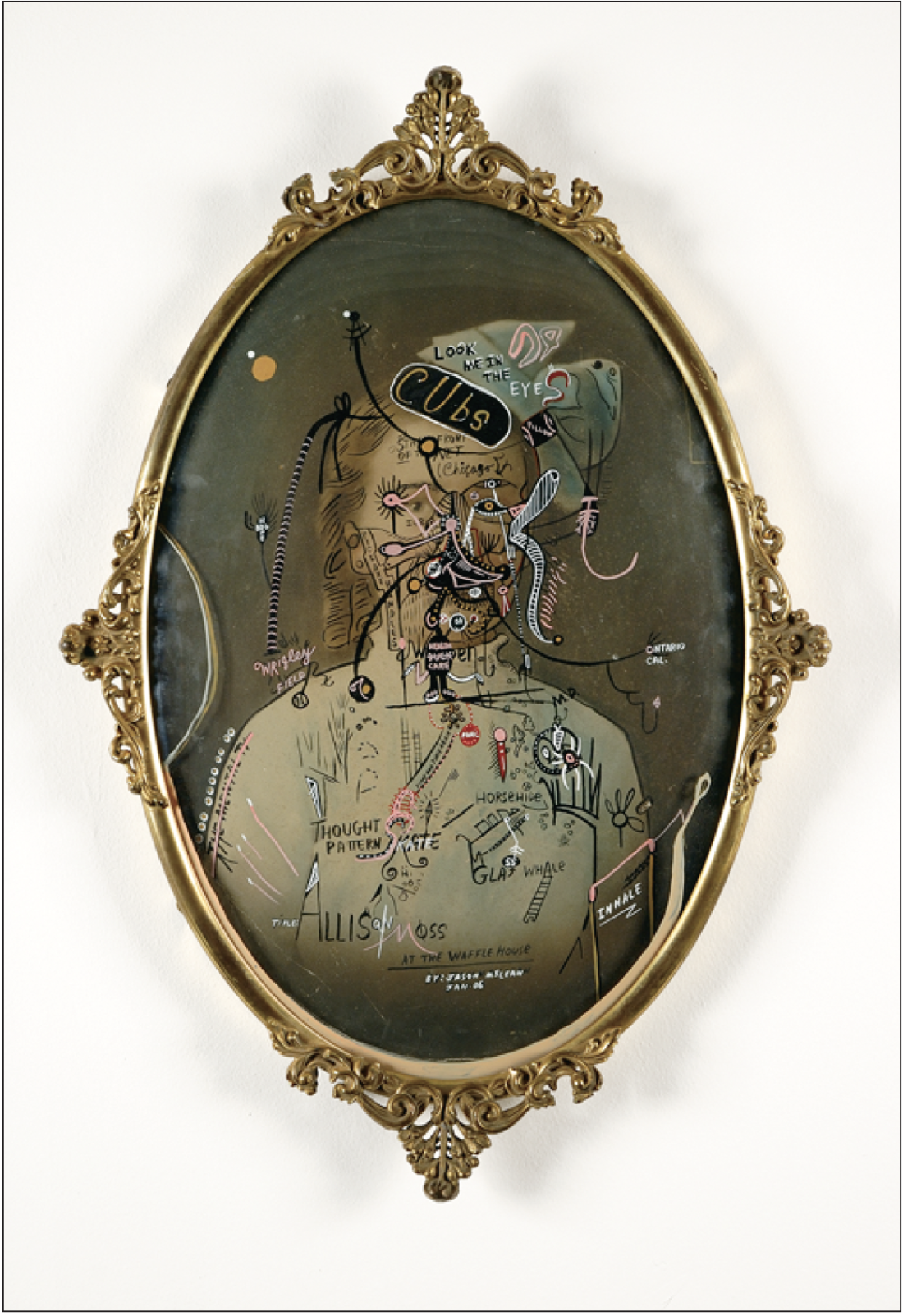

A suite of fading black and white photographs from the 19th century, the morbidly forgotten portraits of grim family members that somehow find themselves in antiques stores instead of heirloom lists, framed in gilt gone greenish bronze, or glazed wood and covered in a convex lens of glass, have ended up in McLean’s show as drawing surfaces. One poseur-aristocratic Canadian circa the Spanish Flu gets a complete LSD makeover, with his formerly creamed back hair now aflame in candy colours and tentacled features. And what once looked to be deceased elderly relatives posed on wicker in the garden are now a fantasia of cubes, masks and Freudian implications. Something about their antiquity, their being pictures that have survived despite familial neglect, makes McLean’s drawing over their surface feel taboo. It is graffiti on lost or discarded memories. By virtue of their ending up in second-hand stores, these classic photographs on card paper are a poorly regarded record of our past, and McLean draws all over them, incorporating history into his reverence for the continuous present.

Jason McLean, Allison Moss at the Waffle House, 2006, acrylic ink on found photograph, 24 x 17”.

Alongside these iridescent vintage photographs are other antique, thrift and dumpster objects he’s tampered with with his drawing style, including the fridge, the Venetian-style swinging wood door of a bathroom stall and an old claw-footed mahogany phonograph player with a drawing carved right onto its woodgrain. One of its feet is bound in gauze, poor crippled antique. Now the phonograph player is doubling as a replica in miniature for the entrance to the Ovaltine Café on Hastings Street in Vancouver, famous for its neon sign, its appearance in film and TV, and as the booth-and-formica studio where many of the collaborations that McLean has done with other artists over the years have happened. Inside this record player’s boxy upright stand, there’s room for a painted hatbox and a set of Pepto-Bismol-pink ceramic records in a file system, each one almost as heavy as 78 rpm vinyl. One of these actually rotates very slowly on the turntable. These ceramics, and a set of spherical objects and pink plates on display in a vitrine, are a collaboration between McLean and Gailan Ngan, a well-known Vancouver ceramicist who lives in the same neighbourhood as McLean and the Ovaltine Café. For McLean’s part, he had the idea to quickly paint seemingly nonsensical jokes and fairly ephemeral drawings on these pastel-coated shapes, for which Ngan provided a masterful sense of colour, texture and heft. These quick, whimsical pieces refer to a series of neon-pink stickers McLean had made previously and distributed at random. As a run of 100 or more Jiffy marker original peel-offs, the spontaneity and wit in the drawings seemed in keeping with the whole roll-ofstickers concept, but as high-quality ceramics, the idea not to make a lot of fuss over the drawings suddenly offers a much more audacious idea of what a drawing can be. David Shrigley, an artist in the UK, has made some of the most profound leaps in this direction, doing drawings and collages so basic you have to cry. McLean is not quite a practitioner of this vernacular absolutism, as it begins to resemble something conceptual. That absolutism, just like illustration or paper or consciousness itself, is a restriction that McLean has never claimed.

Jason McLean, Back in 5 min., 2006, ceramic, 8” diameter. Ceramicist: Gailan Ngan. Photograph: Scott Massey.

Despite a great body of sculptures, costumes, headpieces and tan-coloured London Fog trench coats, his work always seemed to revolve around an astonishing body of drawings. Sometimes these are drawings on baseballs, hockey gloves or goalie pads, but a lot of the time, McLean works on paper. Seen in this show were two large-scale drawings on paper, one of which was accompanied by a Discman playing a piece of music by the Olympia, Washington, throat singer Arrington De Dionyso. Both these drawings are instilled with an unapproachable facility for the free-associative, the transcendent quotidian and the illusion of depth, while at the same time retaining complete two-dimensionality. There’s still a face or two (or seven) that appear within their gestural fields, but these are far away from comic drawings. The compositions are closer to the flow of veins in and out the human heart. Something absurd is pumping away as tight as muscle in the centre of these drawings. There’s comic moments within, funny language combos and eyeballs and big noses, but unlike most comic styles, there are no real animation tropes in McLean’s work, and there’s very rarely any sense of a middle distance. There is narrative and also absolute stillness. “back in 5 min.” The title, referring most directly to the quickness of the automatic writing seen on the ceramics for this show, also acknowledges the poetry in everyday signage, the commonest creations, which McLean always sees as works of art. But especially when it’s posted on the glass door of a commercial gallery, a handwritten note reading: “back in 5 min.” is unquestionably an unknowingly smart drawing—no small observation by the artist Jason McLean. ■

“back in 5 min.” was exhibited at Tracey Lawrence Gallery in Vancouver from May 5 to June 8, 2006.

Lee Henderson is the author of The Broken Record Technique (Penguin Canada). He lives in Vancouver, where he’s working on his next book and writing about art. He is a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.