Janet Werner

Montreal-based painter Janet Werner’s exhibition of recent work displayed a rare combination of artistic forces: the creative muscle of a mature artist exploring, in depth, subject matter she is well known for, yet at the same time maintaining a high level of risk, presenting work energized by invention and full of surprises. Proof positive that, along with her demonstrated mastery of the painterly practice, her creative vigour has, if anything, increased.

Werner is, above all things, a portraitist, member of a longstanding and venerated clan whose legitimate membership dates back to painting’s earliest periods. With this show, she reaffirms her allegiance. Her larger canvases, about the height and width of an erect human, dominate the four walls of a single, big, room. The smaller ones, also near square, usually an arms length in height, create a more intimate environment in an attached alcove. All remain faithful to what has been a central theme of her work for nearly a decade now—a figure of a human, or animal, at the very least full scale, but often larger. The greatest change in this new body of work is the introduction of landscape. The figures are set, consistently, against it. In fact, a few of the smaller canvases mark a further transition away from the figure itself and present only landscape.

Being in the midst of these works is stunning. The word “viewing” is inadequate. Encounter may come closer. For the most part, each image has been arranged so the viewer is at eye level with the compelling eyes of the subject portrayed. The people in the large canvases, if full length, are near life size. If head and shoulders, they are many times human scale, and those who are faces alone—filling a canvas—transcend any idea of the human, becoming cartographic. We are confronted “head-on,” so to speak, with a topography of skin and facial features. This magnification increases both their mystery and the intensity of our regard. Like peering through a telescope at a distant planet, by the very nature of amplification, we study more closely the image we see.

Janet Werner, Fortune Teller, 2008, oil on canvas, 168 x 208 cm. Images courtesy the artist.

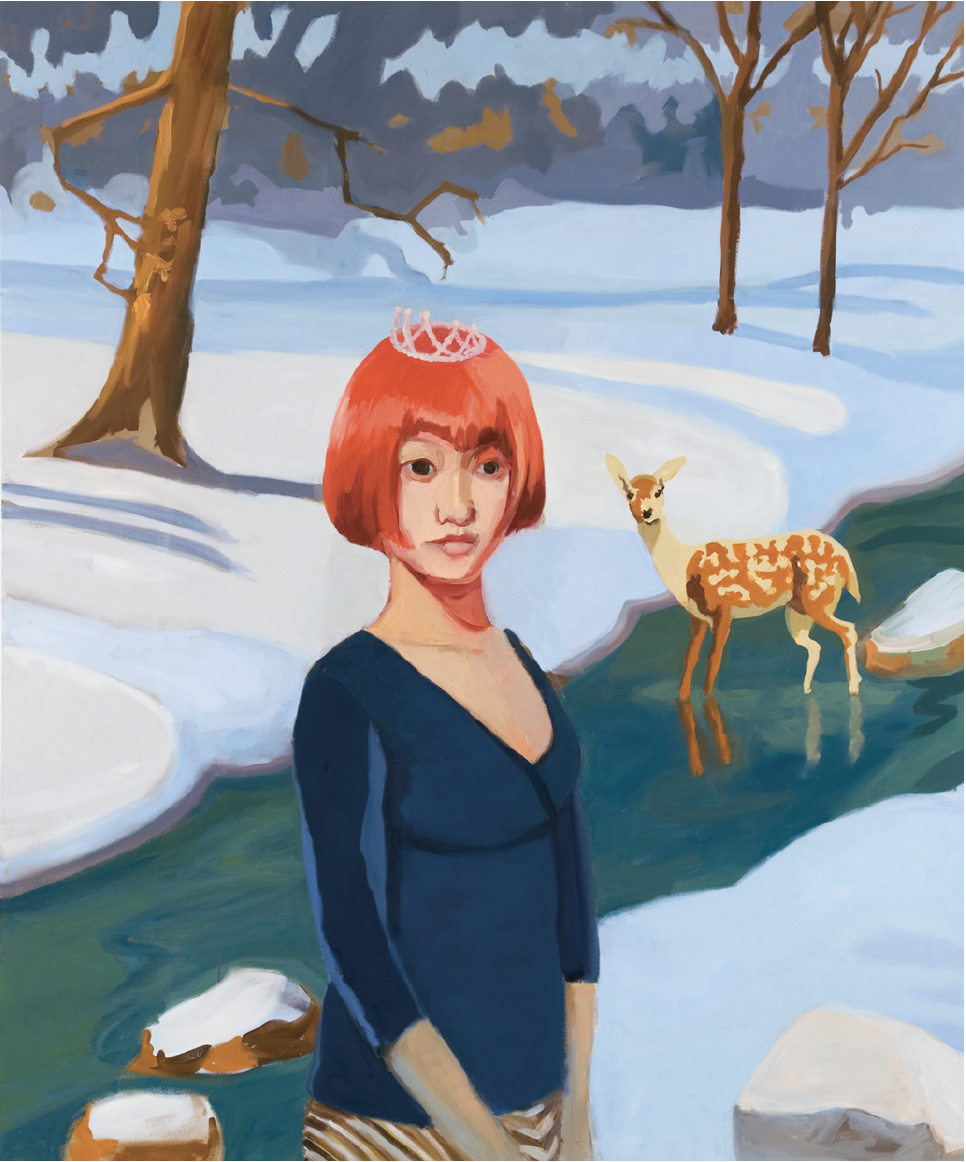

Various animals are also represented. All fall into a class defined in North American French as animales d’accompaniment, which usually means “pet” but can also mean “escort.” And that is what we see. Some are nice little dogs, ones you can keep in your lap. There are teddy bears, too. Real and manufactured pets, ready to be cuddled. Again though, when scale changes, so does our relationship. There is a life-sized spaniel that almost slips into the cultural category occupied by the humans, as actual dogs are wont to do. In Landscape with Girl, Collie dog and Flowers, 2007, a dog much resembling Lassie is definitely in the “escort” class. Someone’s dog, or our memory of the TV dog? Likewise in Girl with Deer in Snowy Woods, 2007, we find a faun much resembling Bambi, though this latter is more about childhood memory than any idea of their taking a stroll together.

The technique is refined, consistent and dexterous, but there is no evidence of an obsession with hyperreal detail. The power of the work comes from the painter’s taking complete aesthetic and moral responsibility for every square centimetre of canvas, of leaving nothing, in the physical sense, to chance. This doesn’t mean a mechanistic obsession with the amount of data that brush and paint can provide. Instead, Werner seems to be working in an entirely different plane. When questioned about the process of her painting, she responded, “I work very hard on arriving at the image. I spend a lot of time working and reworking it in order to get the expression I want, and it involves the process of painting and repainting to simplify information. I try to articulate the forms so that there is an effect of maximum communication with minimum information, so that it is real rather than realistic—and this seems to involve a kind of distillation process.”

Toronto painter David Urban has observed, “The job of the artist is to connect with something that’s valuable and somehow drag it into the future. It’s not a matter of recreating it; it’s a matter of honouring it in a way that becomes viable again.” I submit that this is what we see in every element of Werner’s canvases. These are paintings which are, in the same instant, traditional, current and prescient. What is evident, when we engage these canvases, is her struggle to make work in the present, not forget the past, and impel painting towards its future. Werner has accomplished this, honouring her predecessors, Rembrandt, Diego Velásquez, Fedor Rokotov and Thomas Gainsborough. Yet the urge she shares with them, refined and deepened by the experience of centuries, confronts an utterly modern dilemma. As our shiny new millennium loses some of its gloss, most everybody sees themselves as portrayal worthy: hundreds, thousands, millions of portraits and self-portraits are made, in infinite digital detail, and looked at every year. From the top of Mount Everest to the bottom of a suburban swimming pool.

Janet Werner, Girl with Deer in Snowy Wood, 2007, oil on canvas, 168 x 140 cm.

As evidenced by Janet Werner, not only in the long tradition of painting is the painter’s urge to portraiture still with us, but it would seem the artists’ powers of revelation have survived intact. Werner confronts the present, its faces and its knowledge of itself portrayed, looks at it and makes courageous, unmediated judgements. These are extracts from life and her art’s thick sediment—the essence of a collision of the old with what appears, on the surface, to be new.

Icons of the historic formal portrait are in evidence: a small animal, flowers, veiling, the pose. They shift in and out of deep space, highly individuated but all, at the same time, a summation, a catalogue of a venerable history.

One canvas in the show, Fortune Teller, 2008, is rendered with particularly understated caution: brushstrokes invisible, the subject’s eyes hidden behind dark glasses, the enclosing landscape an anonymous rock-strewn boreal forest. The result is smooth and perfect. The title perhaps raises prescient intentions, suggestive of both our present state and the artist’s pursuits. Are we, all three— the viewer, the portrayed and the artist herself—being chastened for our conceit? Is something here, or is something missing?

Girl with Daisies, 2008, takes the whole matter a step further. The landscape seems benign, the already mentioned flowers in the foreground, a lake, maybe Tom Thomson, maybe F. Scott Fitzgerald, behind. The subject posed in her entirety, eyes gazing into the middle distance, hand raised, perplexed, to her face. They don’t let us rest easy, these eyes. Is she frightened of something she has seen? Or has she just suffered a terrible disappointment? Does the pale, cinema blue light of a full moon bathing her portend an alien invasion, or has she been stood up by her date? What the work does is ask questions. The answer it gives is that Werner’s work, in its full substance and sustained examination of the medium, happily yields no quarter. Not for the viewer, not for the artist. ■

“Janet Werner: Too Much Happiness” was exhibited at Parisian Laundry in Montreal from March 7 to April 19, 2008.

Clayton Bailey is a writer living in Montreal.