James Jean

I have a confession: for many years, I was unable to look at the art of James Jean for longer than a few moments. It was rather like looking into the sun. Too tempting, too dangerous.

There comes a threshold at which talent ceases to be impressive and starts to become onerous. Most people are not equipped, sensually, with the means to engage with artistry beyond a certain point. It is in this place that an artist’s talent ceases to be meaningfully affective and transforms into private amusement (consider, for example, Jimi Hendrix performing a live solo— after a while, it’s not really about the listener anymore). It was when Jean passed through this threshold that I had to stop consuming him.

Fortunately for me, he has in recent years toned down his voracious draughtsmanship and focused more on the production of painting commissions. A body of this work forms the focus of his most recent solo exhibition at the Centre of International Contemporary Art in Vancouver (CICA), his first in North America in 10 years.

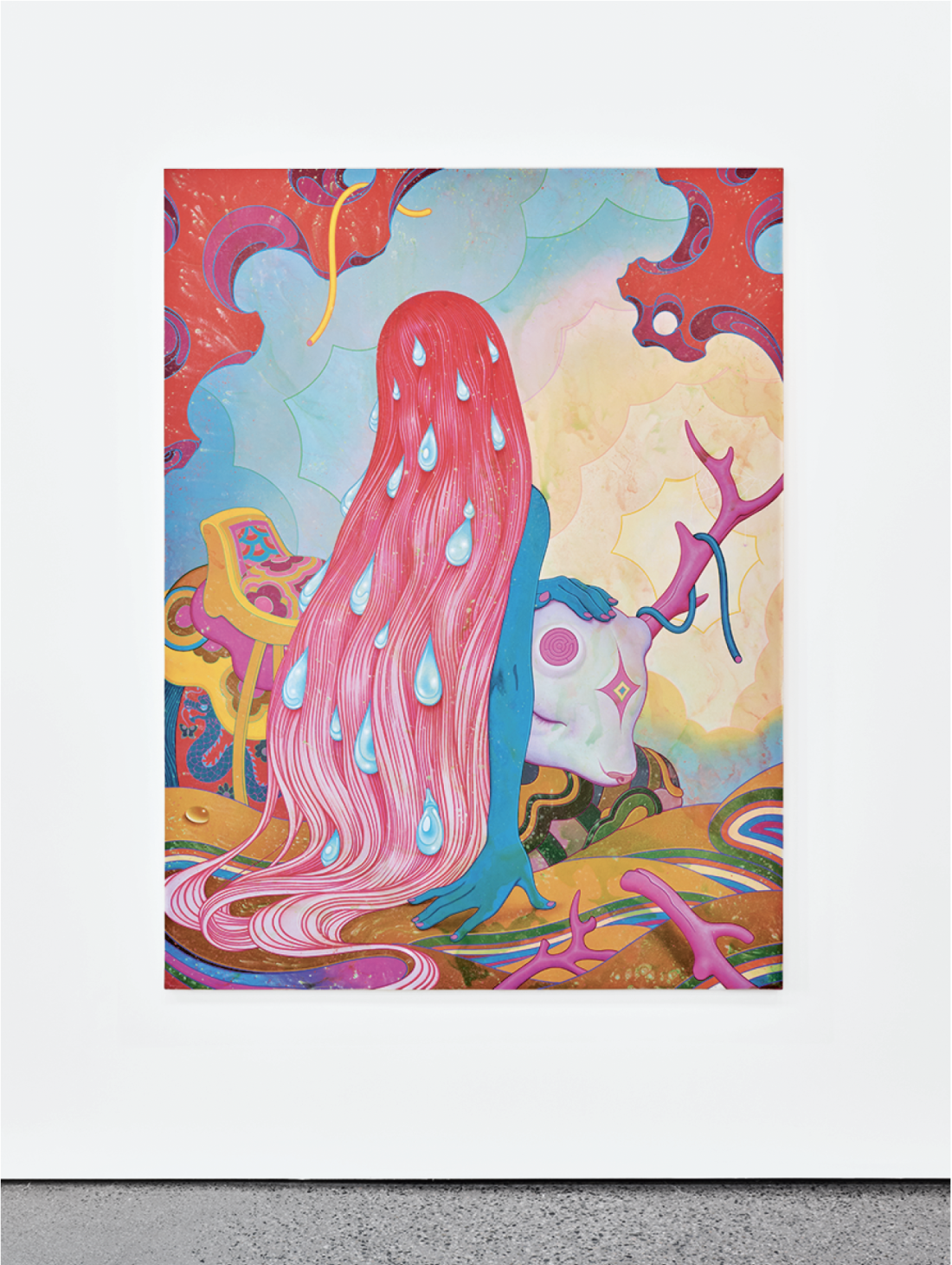

The subjects of “Meadowlark” will be familiar to fans of Jean: luscious, coruscating fields of acid-rich, saturated colour form the planes of ethereal forest glades and floral enclaves, populated by a menagerie of creatures that offer themselves up in sacrifice to a coterie of perennially youthful, amber-eyed forest nymphs and waifish, introverted boys. Slumbering will-o’-the-wisps hide amidst chrysanthemums, hares clamber into the entrapment of all-embracing arms and uplit kindling reveals minute mazes.

James Jean, Deer II, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 203.2 centimetres. Photo: Brandon Shigeta. Courtesy Centre of International Contemporary Art, Vancouver.

Ostensibly, “Meadowlark,” in the artist’s sense of alienation, deals with his heritage suspended across different forms of Asian identity. This theme finds gravity in Vancouver, where many locally based artists evince similar interests. And yet, something feels lost. Perhaps my palate has been worn down by Jean’s saccharine hues, so appealing in my youth, and I recognize all too well his formulaic approach to commission painting. I yearn for the vitality of the sketchbooks he has stepped away from. His earlier drawings were irrepressible, seething paeans towards sinuous form; by contrast, his newer paintings are controlled, staid—entirely lovely, and unsurprising.

One work in particular, Dragon II, feels like a misstep; Jean appropriates totem poles as token compositional devices in an otherwise largely ornamental work. Such a gesture holds perverse resonance at CICA, in the Gastown district, where discount totem poles were sold by colonial artists as tourist tchotchkes for decades, while the Indigenous carvers who originated these forms—deeply laden with specific, contextual histories—were forbidden from making them for the duration of the Potlatch ban (1885 to 1951). As ever, it is abundantly clear that mythos, pathos and blithe aestheticism are more essential to Jean than any specifically bounded cultural hierarchy or concept.

It bears mentioning that it is only in the past decade or so that Jean has charted a career as an independent contemporary artist; much of his work has been focused on illustration for brands such as DC Comics, Prada and, most recently, A24 (most people are likely to recognize his posters for Blade Runner 2049, Everything Everywhere All at Once and The Shape of Water, among others). Jean’s exhibition “Meadowlark” is symptomatic of a larger trend in popular culture: colourful, selfie-friendly exhibitions that promote “engagement.” In recent years, exhibitions by Banksy, Shepard Fairey, Van Gogh, and Takashi Murakami have all been hosted in Vancouver. In these contexts, harmonious composition, visual impact and “content” take precedence over meaning.

CICA (and other institutions, such as the Modern Art Museum in Shanghai) has attempted to intellectualize Jean’s practice. According to the exhibition’s press release, “Meadowlark” reflects “the complex identities forged by migration and globalization” and “transcend[s] traditional visual boundaries, offering a rich tapestry of cultural exploration and identity.” It is worth examining these claims in a contemporary art environment, and particularly in Canada, where the subject of hybrid identity has become the sine qua non of so much artmaking that it is easier to list artists who do not work with this theme in some respect than it is to name those who do.

James Jean, installation view, “Meadowlark: James Jean Solo Exhibition,” 2024, Centre of International Contemporary Art, Vancouver. Photo: Brandon Shigeta. Courtesy Centre of International Contemporary Art, Vancouver. Left to right: Erhu II, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 203.2 centimetres; Dragon II, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 203.2 centimetres; Yonen, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 203.2 centimetres.

Jean’s paintings propose complexity, but in practice they are decidedly uncomplicated. They present serenely organized, unproblematic dreamscapes inhabited entirely by beautiful beings. They are phantasms. Perhaps it would be more accurate to suggest that they embody the fantasies of a successful migrant, the “right kind” of migrant—the migrant whose identity poses no problem to market tastes, who rises to celebrity through hard work and commitment to style. These realms are devoid of the muddiness and confusion so commonly found in the practice of many other Canadian artists who purport to examine the same themes. CICA is located only a few blocks from Vancouver’s historic Chinatown, where many of the district’s older businesses and buildings have ceded to more sanitized, Western-friendly visions of Chinese culture.

But perhaps the imperative to intellectualize Jean’s practice is itself unfair; it is a trapping of the institutional logic that has historically served to support artists who explicitly participate in canonical art histories, while disregarding those who have followed a separate path.

Tellingly, in a wall text, curator Mika Yoshitake quoted Walter Benjamin’s reflections on Art Nouveau. Benjamin wrote (in “Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” Illuminations, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc, 1968): “It mobilized all the reserve forces of interiority. They found their expression in the mediumistic language of line, in the flower as a symbol of the naked, vegetable Nature that confronted the technologically armed environment.”

Though I cannot imagine Benjamin would have appreciated the easiness of Jean’s paintings, there is yet something here worth considering. If, instead of treating Jean’s work as some manifestation or response to a diffuse form of globalized identity, one were to see it for what it is—as an expression of something deeply singular, an introvert’s play space lovingly writ in acrylic—then it accrues greater meaning. It feels refreshing to encounter the work of an artist who is unapologetically committed to creating beautiful things, particularly in Vancouver, a city that has for much of its recent history held a limpid disregard for the uncomplicated fabrication of ornamental form.

I look at these paintings, to my chagrin; and yet I look, and look, and look. ❚

“Meadowlark: James Jean Solo Exhibition” was exhibited at the Centre of International Contemporary Art, Vancouver, from July 25, 2024, to September 15, 2024.

Rhys Edwards is an artist, writer and curator. His writing has appeared in Canadian Art, C Magazine and The Capilano Review, and he lives and works on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, Kwantlen, Katzie and Semiahmoo nations.