Jack Goldstein

For his 1972 thesis show at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where he studied with conceptual pioneer John Baldessari along with several other members of the Pictures Generation, Jack Goldstein equated the disappearance of his body with the appearance of a mental image. While this early work never offered up any “pictures” as such—to use the term coined by Douglas Crimp in his eponymous 1977 exhibition at New York’s Artists Space, featuring the work of Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Philip Smith, Troy Brauntuch and Robert Longo—the conceptual groundwork was already laid. Buried for the duration of the performance, the artist breathed through a plastic tube; his presence above ground was only registered by a blinking light synched to his heartbeat and placed some distance away. It is this same psychological distance and self-effacement that defined how pictures appropriated material from advertisements, Hollywood cinema and other shared cultural properties.

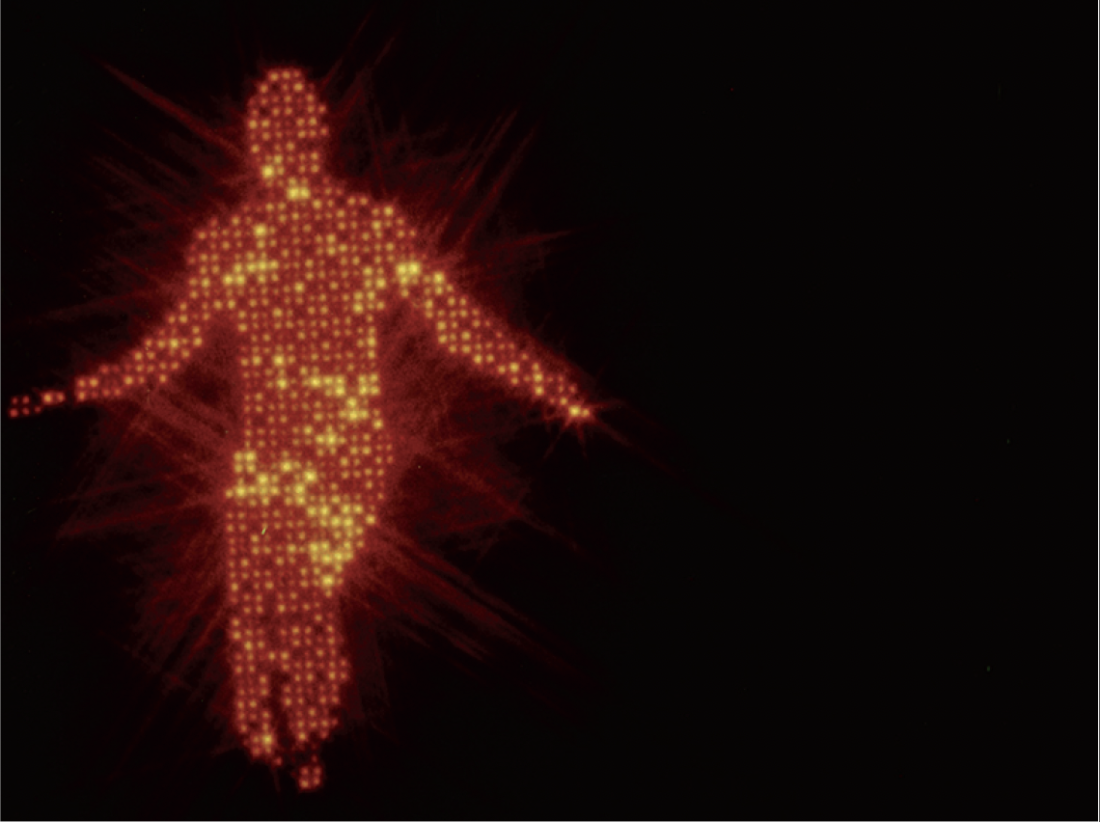

Goldstein’s pictures are paradigmatic in this regard, despite being less immediately recognizable than Longo’s falling figures or Cindy Sherman’s noirish film stills. Organized by guest curator Philipp Kaiser at the Orange County Museum of Art before coming to The Jewish Museum in New York, “Jack Goldstein x 10,000” capitalized on the curiosity surrounding the reclusive Montreal-born artist who largely disappeared from the art world in the 1990s, committing suicide in 2003 while living in an obscure part of Los Angeles. Modest in scale, Goldstein’s first American retrospective had a thematic cohesiveness that belied the variety of media on display: 16mm film (black-and-white and colour, silentand sound), vinyl records, photography, sculpture, performance posters, painting, installation and writing. With a name so apparently unremarkable that it might appear 10 thousand times in a phonebook, Goldstein is best known for a series of 16mm colour films that evoke the sublime and the generic in equal measure. In Shane, 1975 (3 min), a Hollywood-trained German shepherd barks repeatedly on cue. In Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1975 (3 min), the MGM lion roars against a monochromatic red background. The Jump, 1978 (26 sec), swaps the red background for black, using rotoscope to transform a diver into a figure of red-golden light. Installed separately near the exhibition entrance, The Jump was projected onto a red wall in a space barely illuminated by two fluorescent sticks. The same whirring projector has become a symbol of technological obsolescence in recent work by Tacita Dean, Rodney Graham or Elad Lassry. Lassry is a 2003 CalArts graduate whose films, photographs and performances bear the influence of Goldstein’s manipulation of cinematic clichés.

Jack Goldstein, The Jump, 1978, 16mm colour silent film, 26 sec., ultraviolet light. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne, and the Estate of Jack Goldstein. ©Estate of Jack Goldstein. Photographs: courtesy The Jewish Museum.

Historical yet somehow contemporary, Goldstein’s work often feels disorienting, leaving viewers unsure about where they stand visà- vis inside and outside. Burning Window, 1977, dramatizes this uncertainty. With nothing more than a vinyl window, electric lights and red film, the installation simulates the feeling of watching an outdoor blaze from the safety of a house interior—or is the fire inside? Portfolio Performance, 1976– 85/2001, presents a series of posters describing live pictures like Two Boxers, 1979, for example, which calls for a stage, red and white lights, professional boxers and “heroic” music. The performanceconstructs three pictures that ultimately collapse into one: first, Prussian marching music plays while the audience sits in darkness; second, the boxers fight in silence, illuminated by a white strobe light; third, the boxers, now bathed in red light, freeze into a still image; lastly, the audience contemplates an empty stage, the picture now purely mental. Elsewhere, pictures move with ease between the visual and auditory registers. Suite of 9 Records with Sound Effects, 1976, combines generic forms with equally generic sounds—wrestling cats, a tornado, a burning forest—that nevertheless manage to be mysterious and even menacing.

The next set of rooms chronicles Goldstein’s much maligned turn to large-scale painting in the late 1970s. In Untitled, 1979, tiny astronauts float in the vacuum of space with their tethers cut; the surfaces are deliberately impersonal and bear no trace of brushstrokes. The paintings from the 1980s, made completely by assistants from stock photographs, verge on hyperrealism and depict such phenomena as aerial bombing, sheet lighting and volcanic activity. Later canvasses move closer to abstraction as they transpose thermal images of skin and other organic materials into paint, before Goldstein abandoned the medium entirely in the 1990s. Marked bya return to film and experimentation with writing, the production of his final years was contained in the last room, this time separated by a door from the rest. Lasting a mere six-and-a-half minutes, the 16mm film Underwater Sea Fantasy, 1983/2003, nevertheless took two decades to complete. Suffused with blue and yellow and sometimes red and white, archival footage of the now familiar volcanic eruptions and lunar phenomena is here intercut with sublime shots of undulating marine life. Goldstein’s writing takes the form of two works in progress: Selected Writings, 2002, consisting of 17 photocopied volumes of philosophers’ quotations arranged three to a page, and Totems: Selected Writings, 1988–90, a single box containing 100 computergenerated pages that combine appropriated text with clip art. Still committed to an aesthetics of selfeffacement, Goldstein thought of these text-based appropriations as a form of autobiography.

Jack Goldstein, Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer, 1975, 16mm film, colour, sound, 3 min. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin/ Cologne, and the Estate of Jack Goldstein. ©Estate of Jack Goldstein.

The OCMA catalogue is a valuable addition to the literature. One highlight is a new essay by Douglas Crimp where he corrects his own 1977 description of A Ballet Shoe, 1975 (19 sec). In a 1979 version of that essay published in October, Crimp wrote of the 16mm colour film that “the foot of a dancer in toe shoe is shown on pointe; a pairof hands comes in from either side of the film frame and unties the ribbon of the shoe; the dancer moves off pointe…” Given another chance to describe what transpires in the picture, Crimp now sees that not only are the male hands (Goldstein’s) already inside the frame before they start pulling the ribbons apart, but these ribbons also have nothing to do with the dropping foot. This is because the real, functional ribbons were knotted— not tied in a bow—and then tucked out of view. The foot never slumped to the ground because the merely ornamental ribbons were loose; rather, the dancer’s considerable skill enabled her to descend from pointe slowly and smoothly. That Crimp—now a balletomane— missed this in 1977 and again in 1979 speaks to the slipperiness of pictures as mental images. Far from being reducible to linguistic meaning alone, these works always beckon the viewer to look again. ❚

Milena Tomic writes about contemporary art and teaches art history at OCAD University and the University of Toronto Mississauga.

“Jack Goldstein x 10,000” was exhibited at The Jewish Museum, New York, from May 10 to September 29, 2013.