Jack Chambers

This current exhibition at Museum London of the silver paintings combined with his films is the best exhibition of Jack Chamber’s work I have ever seen—and I think I have seen them all. In its brilliant conception and stunning installation, masterminded by Mark Cheetham and Ihor Holubizky, it cannot be bettered. What has been achieved here is the release of Chambers’s work from the regionalism with which it has long been identified. With a focus on a particular period of no more than two years, Chambers has been persuasively relocated in a postmodern environment likely set to appeal to a select audience of viewers of contemporary art to whom his work would be relatively unknown. In part this is because few painters (Michael Snow is one) can match what Chambers in the ’60s had, almost silently, already done.

I say almost silently because the body of silver paintings shown in this exhibition has never been seen before along with the films that are conceptually related to it. I, who saw many of these “aluminum” paintings being painted (“silver is refreshingly neutral,” Chambers explained to me in an interview published by Coach House Press in 1967) and watched many of these films being handmade, did not see them in the way they can be seen now in this exhibition. They are a body of work by an artist interrogating the very nature of art (which includes film) and emerging with a new understanding of its perceptual possibilities. What I saw being done, I had not seen as done.

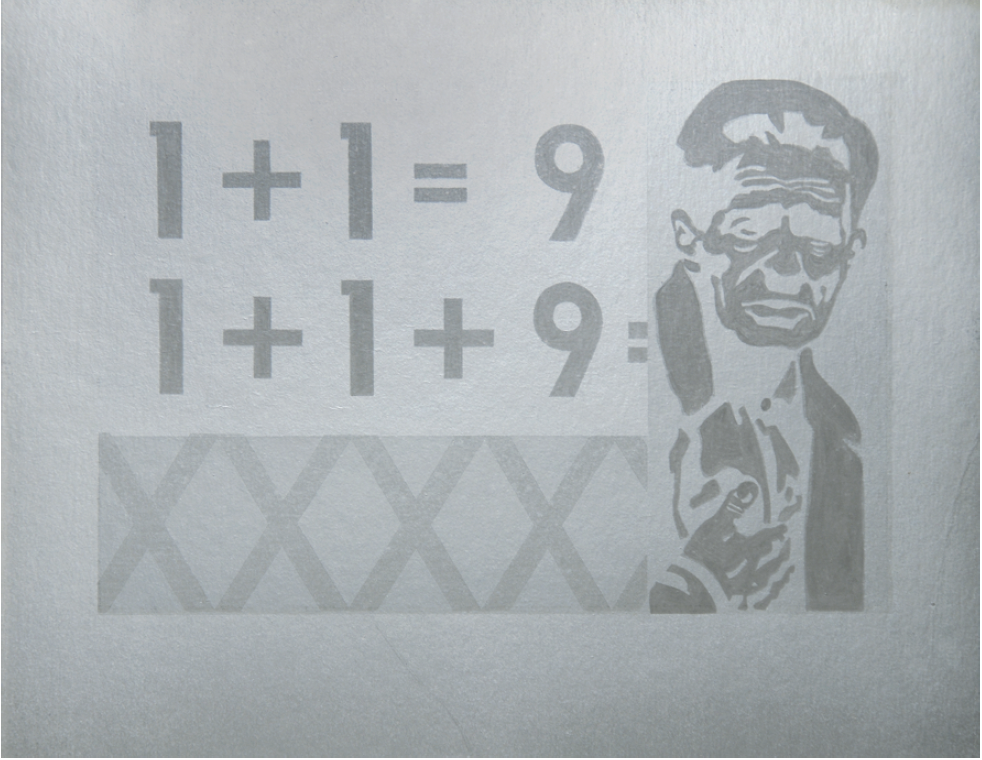

Jack Chambers, Plus Nine, 1966, aluminum and oil paint, and mixed media on Douglas fir plywood, 129.4 x 190.5 x 2.4 cm. Photograph: John Tamblyn. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, purchased 1966.

“[H]e dances attendance upon the coming-into-being of something recognizably NEW,” Stan Brakhage wrote of Chambers’s films in the program notes for their showing at the University of California Art Museum in Berkley in 1977. Seen in the context of the films, the “something entirely NEW” applies equally to the silver paintings. In Madrid at the Escuela Central de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Chambers learned to draw in the classical manner, from the live model. Returning to Canada, he used photos, “a few visible appearances,” because, he insisted, it was “the still-life presence of the figure he was interested in.” Carried to a new stage entirely, “the still-life presence” in the silver paintings is reduced to a condition not unlike the frames of an undeveloped film strip, which, when he was making the film, hung like clothes on a line in Chambers’s studio waiting to be developed. “Olga Visiting Mary in the present exhibition isn’t,” he explained in 1977, “the description of a visual moment; it’s the accumulation of experienced interiors brought into a focus.” The show, in short, is a revelation of Chambers’s mind in creation, a mind that, having focused upon space as what he calls “perspective and colour modulation,” is now in the silver paintings turned to time, which, he argued, “belongs to movies.”

In our interview Chambers described his silver paintings as instant movies, by which he referred to a perception that shifts from positive to negative (now you see it, now you don’t) as the viewer moves back and forth in front of them. The movie is the movement of the viewer, whose body becomes a hand-held camera not unlike the camera used by Chambers in his filmmaking. In the film Circle, we see Chambers holding his camera and winding it before locking it up. When he further describes his movies as “personal films,” the personal, as he explains it, does not refer simply to himself. It refers equally to the viewers who hopefully bring their own perceptions to them that, in the case of the silver paintings, they must bring if they are to see what is there.

In the paintings and films, Chambers was creating an audience for art in Canada that Spain, with its long history, already had. It was in Spain that he’d received his formal training. Unlike that country in Europe, Canada, he realized, had not constructed a mirror in its art in which it could see itself. “And still I gaze—and with how blank an eye!” wrote Coleridge in his poem “Dejection: An Ode,” describing his depressed (deprived) state. In this sense, Chambers, returning to Canada in 1960 to make it his home nine years after fleeing it, knew that, as an artist, it could only become his home if others also inhabited it as their own. The issue was a matter of cultural life and death. It is the literal, physiological dimension of this cultural issue that Chambers was exploring in this astonishing body of work. His life in Canada depended upon “a few visual appearances,” which both in the films and the silver paintings kept disappearing. In his studio, death was literally in the air he breathed.

Jack Chambers, installation view of “the light from the darkness, silver paintings and film work,” exhibited at Museum London in 2011. Photograph: John Tamblyn. Courtesy the estate of Jack Chambers.

The regionalism that is raised in an exhibition that appears deliberately to avoid it is, I suggest, an issue that in Chambers’s work cannot be avoided. Indeed, no art can avoid it. It can only be radically re-conceived or redefined in the way, for example, Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie redefines the Manhattan landscape or like a Jackson Pollock all-over action painting does. The challenge of regionalism, one that Chambers confronts, is the struggle, still largely in vain, to make the globe our home. Chambers’s film Circle, shot for a “couple of seconds” each day for a year by a camera set in a boxed-in hole cut into his kitchen wall facing onto the backyard, was a bold and original beginning. What was once in his hands was now out of his hands.

There is a danger that this highly focused Chambers’s show, which makes enormous, but rewarding, mental as well as physical demands on viewers, may, by the sheer brilliance of its conception and installation, appear to reduce to a lesser level the art that came before and after it. What came after it is “perceptual realism” (in no sense a regression) and the late paintings associated with his two trips to India in search of a cure for leukemia, which may have had its origin in the lead-based silver paint sprayed directly from the can without using a mask in a non-ventilated studio. These paintings are as fine a body of work as Chambers ever achieved. As for the films, they are as original as any filmmaker has ever conceived. “There are no ‘masters’ of Film in any significant sense,” Brakhage explained in his Program Notes. “There are only ‘makers’ in the original, or at least medieval, sense of the word.” Bringing them together—not unlike what has been done with the work of Andy Warhol—turned the long gallery of Museum London, with its tunnelled ceiling and its two smaller outreaches, into a living organism, which, with its extended fins, moves with a sound of its own through the unconscious depths of a vast sea toward a consciousness that Chambers, and viewers, are in the mysterious process of bringing into being.

Chambers described consciousness as the “essential gesture.” The unconscious is whatever is still “gesturing in the invisible.” This exhibition of the silver paintings, juxtaposed with the films, brilliantly explores the “gesturing in the invisible.” The final phase, waiting now to be seen as a result of the new expectations aroused by this show, is the “essential gesture” that, as “evermore about to be,” lies waiting within it. Attention is finally being paid. ❚

“Jack Chambers: the light from the darkness, silver paintings and film work” was exhibited at Museum London from January 15 to April 3, 2011.

Ross Woodman is Professor Emeritus at the University of Western Ontario and is the author of numerous books and articles on the English Romantics, religion, poetry and modern art.