Jack Butler

There are two questions posed by The Red Head Gallery on its announcement of Jack Butler’s exhibition, “Dark Body.” The first is, “Could the body stand in the place of the limen between two historically defined solitudes?” The second question is, “Can the body be represented as an ontologically transparent layer through which art and science are mutually visible?” Question two seems to me more potentially fruitful than question one. Question one, which appears in an essay from 1986 by Jerome Bruner titled “Two Modes of Thought,” in Actual Minds, Actual Worlds (Harvard University Press), though Red Head leaves it unattributed, is a bit shaky, not only because of the word “limen” pinned to its lapel, but because the “two solitudes” Bruner mentions—the well-examined polarities of disinterested abstraction in art (“subjective expression”) and disinterested abstraction in science (“objective cognition”)—have been so frequently intersected and interpenetrated that as categories, they are too porous and tattered to stand as fortress-like “solitudes” anymore.

The second question is self-answering, and therefore not a genuine question; the obvious answer is, of course, yes, and that yes stakes out the territory Jack Butler has been prospecting for a quarter of a century.

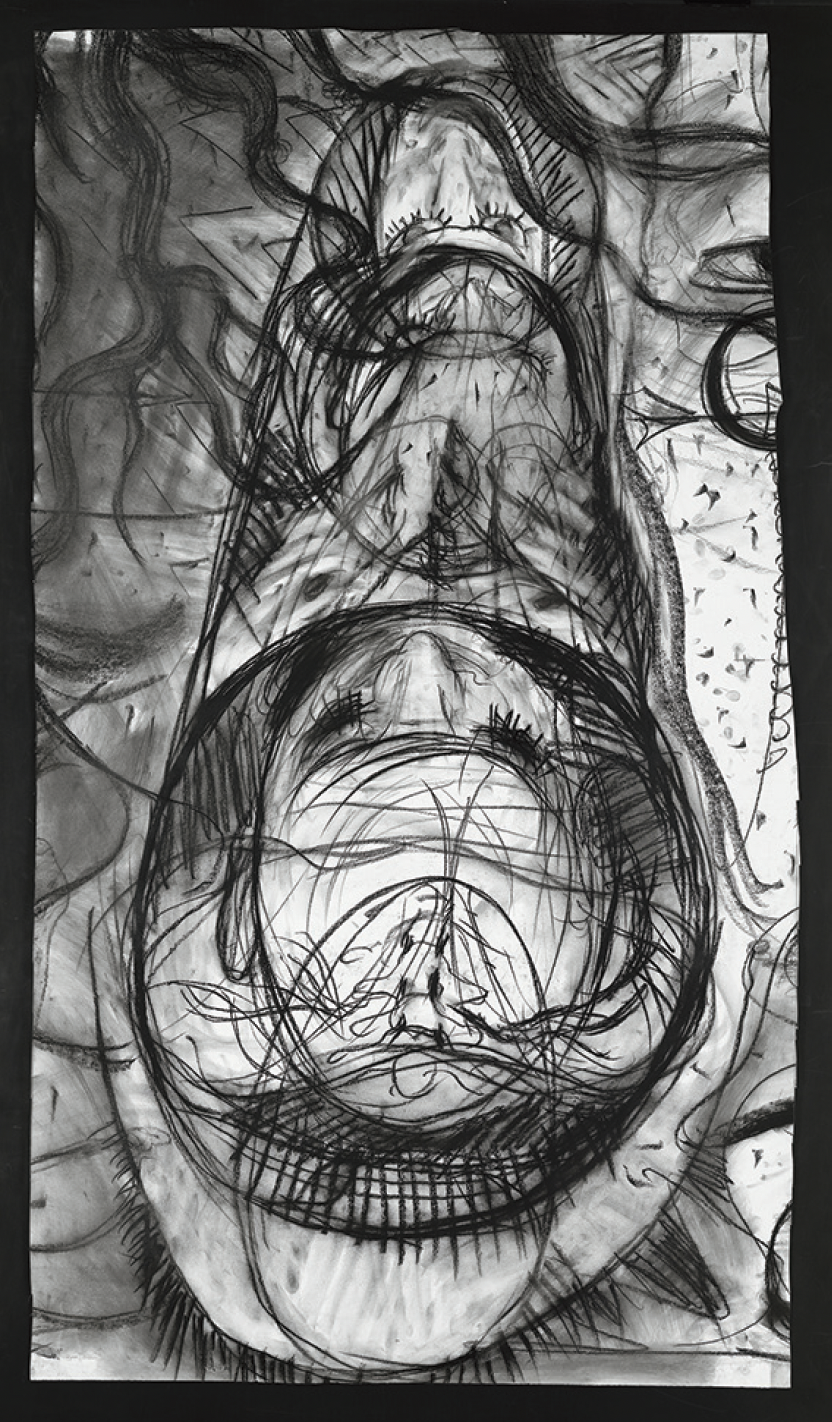

Jack Butler, In the MRI: Coffin and Chrysalis, 2011, charcoal on paper, 51 x 28 inches. All images courtesy the artist.

“Dark Body” apparently arose as an exhibition from within the nervous textual opacities of an ambitious three-thousand-word essay Toronto-based art and film historian Andre Jodoin spontaneously penned after discussions with Butler “about the nature of an art practice.” This essay is, in fact, the source of the Jerome Bruner citation. That, and a lot more, including nuggets from Jodoin’s great and worshipful dependence (half irritating, half infectious) on The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, by Gilles Deleuze and Tom Conley (University of Minnesota Press, 1992). It was this essay of Jodoin’s which led to his serving as the curator of “Dark Body.”

The exhibition is essentially a small, neatly ordered retrospective. Given that there are only 10 works in the exhibition and that they allude to or attempt to represent some of Butler’s many theatres of exploration going back to 1990, a certain nimbleness is required of any serious visitor to exhibition. The four vividly modelled, highly sculptural, black and white digital photos—still frames from Butler’s animated “Genital Embryogenesuis” research project from 1976–80—remain remarkable (“the cloacal channel, by investigation, becomes the vestibule of the vagina and urethral opening…”) and curiously re-mystifying in the very course of seeming to de-mystify the body’s presumed, and always desired, hectic Romanticism of itself. Cloacal channel as vaginal vestibule indeed!

Similarly, Butler’s two feathery, rather spidery “Serpent Brain” charcoal drawings from 1990 (one designated “Black” the other “White”) seem to be about the old urgencies, thrashing and pulsing with erect cocks and mysterious oval absences—pussies, mouths, black holes—in contention.

“I think of paper as my skin,” Butler told me, as we strolled the exhibition, “in order to re-embody the life of the material,” and not the least impressive of his graphic accomplishments is to draw in a way that never lets the drawing cut loose from his incarnating ponderings. His In the MRI: Coffin and Chrysalis, 2011, keeps a tight grip on a personal medical voyage of exploration undertaken physically by the artist and extrapolates, from raw experiences, bodily-medical real-time into the kind of quiet examination that leads to poetry.

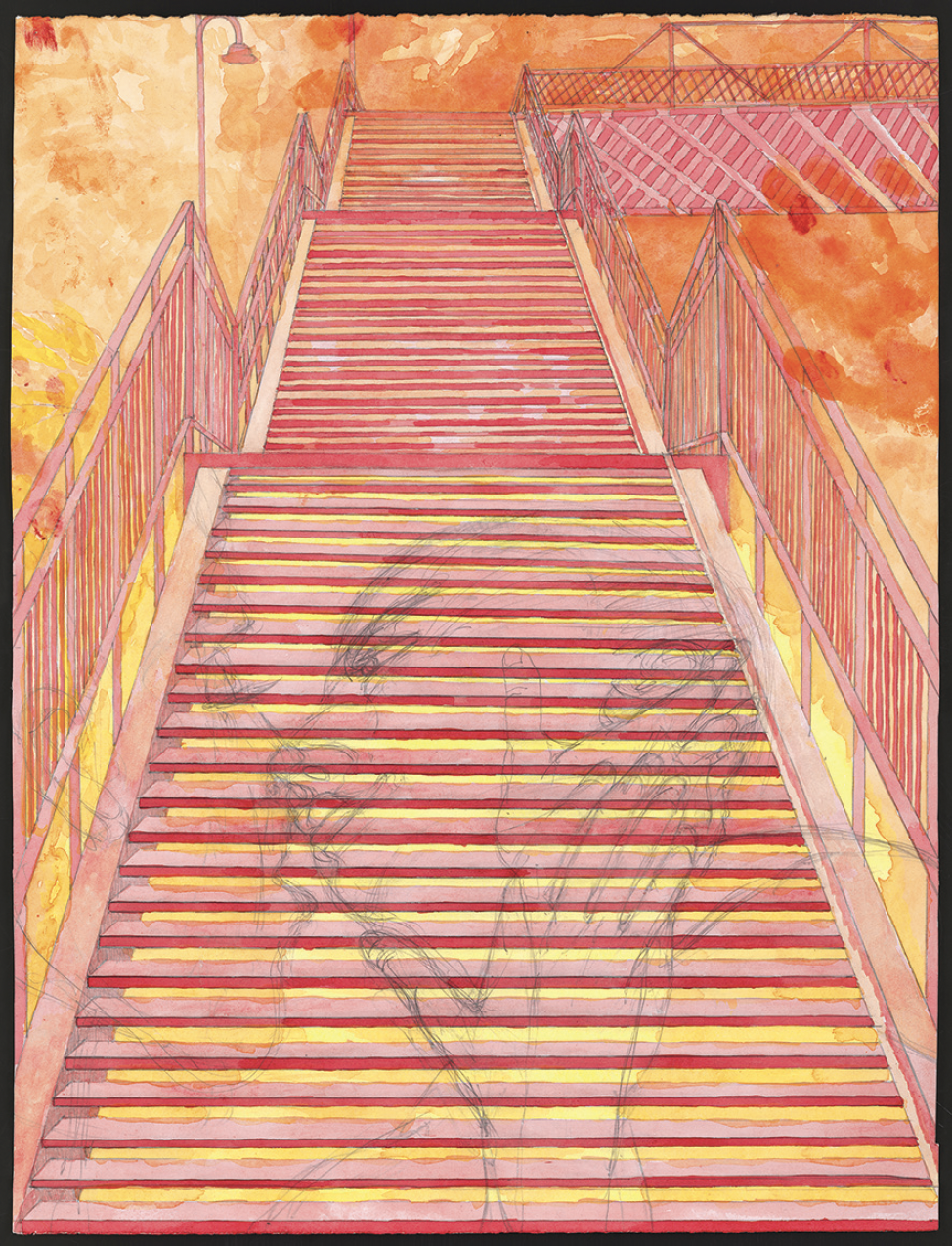

There are two small graphic drawings here that strike me as being among the strongest works in the exhibition: The Steps to the Dundas West Rail Bridge (in Anticipation of the MRI), 2012, and The Red Steps: Love and a Fear of Heights, 2013.

Jack Butler, The Red Steps: Love and a Fear of Heights, 2013, graphite and gouache on paper, 25 x 19 inches.

The first drawing of these long intimidating flights of steps, rendered with what seems at first daunting architectural precision, is red, gold, hot, splotchy, fearful. Apparently his having to climb them is a kind of imposed prescription for building up his strength (Butler the Stairmaster) prior to his journey down the rabbit-hole of the MRI machine. They are too high. They give him vertigo. He draws the enemy steps. The second steps drawing, made two years later, is a golden Jacob’s ladder (against a heavenly blue sky)—a stairway to paradise, the steps softened by angels or angelic thoughts. Intimidation has been gentled into contemplation; the viscous has softened into the visionary.

The centrepiece of “Dark Body” is Butler’s Occam’s Hand, 2014, a touch-sensitive audio drawing installation in collaboration with sound artist Chandra Bulucon and software designer Doug Black. There’s a slanted table, the surface of which is covered by pencil-drawn hands in various attitudes, sharing the tightly packed space with handwritten texts that eddy in and around the hands. There is a horizontal row of speakers across the top of the drawing board.

Fit your hand into one of Butler’s already available hand drawings and you will hear one of Bulucon’s pleasing lengths of electronic music. What to do with the not always legible rivulets of text that flow around the hands is more problematic.

Maybe William of Ockham (circa 1287–1347), after whom the piece was named, had the right idea, suggesting that among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected, the fewer assumptions being made, the better. If I can’t read the scrawly texts that float around the big drawing, why not assume I don’t have to?

Maybe by placing my hand firmly on the paper and releasing Bulucon’s music—one selection at a time or with multiple hand-pressings, several all at once, I have somehow sidestepped proscription, explanation, guidance, suggestion, other modes of adjacent thinking—and gone directly (perhaps stupidly) to the sublimity of pure sense. Isn’t this what Jack Butler himself ultimately recommends? ❚

“Dark Body” was exhibited at The Red Head Gallery, Toronto, from May 28 to June 21, 2014.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.