Jack Burman

The spectral beauty of Jack Burman’s photography lures us into loving what we most fear to see. His subjects— preserved human remains—are lit and displayed as works of art. Burman has travelled the world to find collections of medical specimens or ancient mummies, selecting pieces with the most compelling sense of life-in-death. The unsettling glamour of decay, seen as pure colour and form, is balanced by the shock of what these images reveal about the dead. Burman brings an unflinching, if reverential, eye to his subjects, whose every feature—corroded by air or placidly floating in liquid—is illuminated. There’s an assumed intimacy between living viewers and the dead, who might be looking back at them.

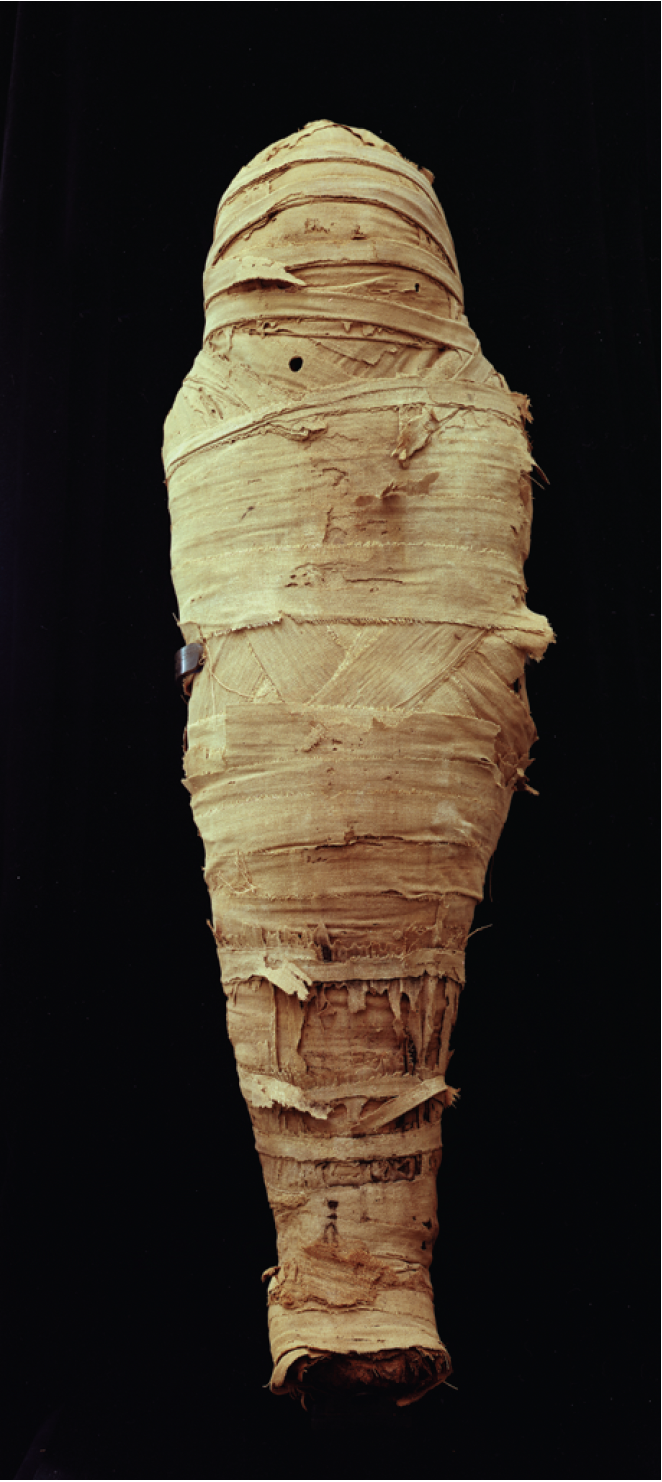

Jack Burman, Egyptian Mummy, 2005, colour photograph on archival paper, 40 x 20”. Edition of 8. Images courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

The photographs are large format, ranging from 56 by 64 centimetres to 122 by 170 centimetres, taken with a vintage bellows camera, which allows for extraordinary detail. He makes no digital alterations, and uses no wax casts or other artificial forms. All images in this show are in colour, except for one black and white shot of a ghostly head, the eyes staring, the mouth drawn open as if in ecstasy. Three views of mummy heads—two Egyptian and one Peruvian— show how flesh can become leather while hair may maintain its colour and texture. Empty eye sockets still seem to see. A photograph of a skull fragment from Oceania converts bone to abstract sculpture. Perhaps because they are so very old and so transformed by time, the mummies project an imperturbable grandeur, like carvings from ancient tombs. A view of one entire mummy, still wrapped in linen, has a monumental gravity.

More uncanny are the images of people—or parts of people—preserved by anatomists, so skilfully that their flesh seems to breathe. Usually found in out-of-the-way places, often hidden in storage rooms, they were once used as teaching tools in medical schools, and seem to have been prepared with reverence. Burman, as well, approaches his subjects as sacred presences. One particularly gifted anatomist, Dr. Pedro Ara of Argentina, contributed the partial face of a young woman, whose expression is idyllic. (This is the same Dr. Ara who preserved the body of Eva Peron.) Another young woman’s head, preserved in a bell jar, could be dreaming, long-lashed eyes cast down, a pensive look about the mouth. Due to the embalming materials, which include paraffin in some cases, each eyelash, each pore, is visible and gleaming. A single hand and forearm looks like a wax model laid out upon a museum display case, but it once opened and closed and maybe caressed someone’s skin.

Burman’s research tells him that most of the specimens were made between 1850 and 1940. Such objects are obsolete as teaching tools now, and many have been relegated to back rooms. After the passage of so much time, little or no information is known about these men or women and those who preserved them. The mummies, of course, are even more anonymous. Burman is content with the mystery and gives no context for his images. The titles merely indicate the country of origin and date of the photography. His tendency, he says, is to “Leave most things unknown.” For while the body parts were prepared with a measure of scientific detachment, they now arouse a mixture of fascination and dread. Knowing so little about them, we can see only what they have become: sensual images of decay.

Jack Burman, Iglesia de San Francisco Javier – Tepotzotlán, Mexico, 2002, colour photograph on archival paper, 50 x 40”. Edition of 8.

Burman began his explorations of death’s physical remains in the 1980s, in the catacombs of Sicily. As driven as his hero, Herman Melville, he wanted “to go farther out, as far as I could go, be utterly changed.” In his photographs of the dead, he finds insinuations of life, while confronting the solidity of death.

The exhibition also includes two explosively vigorous views of Baroque church altars, one in Mexico and one in Germany, and a print of a Portuguese chapel constructed of skulls. Burman’s belief is that these sensual spaces, bursting with carved and gilded life, correspond to the physical amplitude of his body photography. Just as his views of the dead focus on the richness of detail—pores, hair texture, flakes of skin—his churches have an over-the-top refulgence. Both kinds of work are “on the other side,” he says.

One of Burman’s favourite quotes, from the 18th-century poet Novalis, is “chaos in a work of art should shimmer through the veil of order.” Certainly, in these photographs, one feels the strain—and the shimmer—of beauty from the shadows. ■

“Jack Burman: Chaos Shimmers (Through the Veil of Order)” was exhibited at Clint Roenisch Gallery in Toronto from April 15 to May 20, 2006.

Kate Regan is a Toronto-based arts writer.