Jake and Dinos Chapman

In the mixed-media vitrine Kontamination…, 2009, one of the initiating encounters at “Come and See” at DHC/ART, there are two texts of note: one mentions Nietzsche (the silent ambassador of the show) and the other is a Stephen King novel, Desperation, splayed open so that you could, if you cared to look, see the words “Go on” on the upper right corner of the page. This of course recalls Beckett’s aporic echo concluding The Unnamable: “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” It’s an apt mantra for the Chapman canon: like many of Beckett’s characters, the work of Jake and Dinos Chapman proceeds by aporia—repetitious and sometimes meaningless gestures that amount to pacing rather than progress. And in this, the largest Chapman exhibition ever shown in North America, there is a seething dynamism of back and forth and in and out, and a mass of material that points to the centre of nothing or the edge of impasse.

As much as I want to dismiss Jake and Dinos Chapman for the volume of their message and dislike them for the smugness of their conjoined omniscient voice, I must compliment their skill at taking the moment’s pulse and then accelerating the beat tenfold into a convincing mimicry of a modern world set to exhaust itself. It is into the benign spaces of everyday practice that the Chapman brothers insert themselves with such exactitude by saturating our ocular faculties with a kind of scary-clown image, which later unexpectedly reveals itself in mass-produced variety on deceivingly inert surfaces such as window panes, computer screens, mirrors, media images or the box containing the thing we must possess. It is tiresome business ‘seeing’ and seeing the self seeing in a reflective material world; and it is this particular apperceptive fatigue that “Come and See” so readily gestures towards.

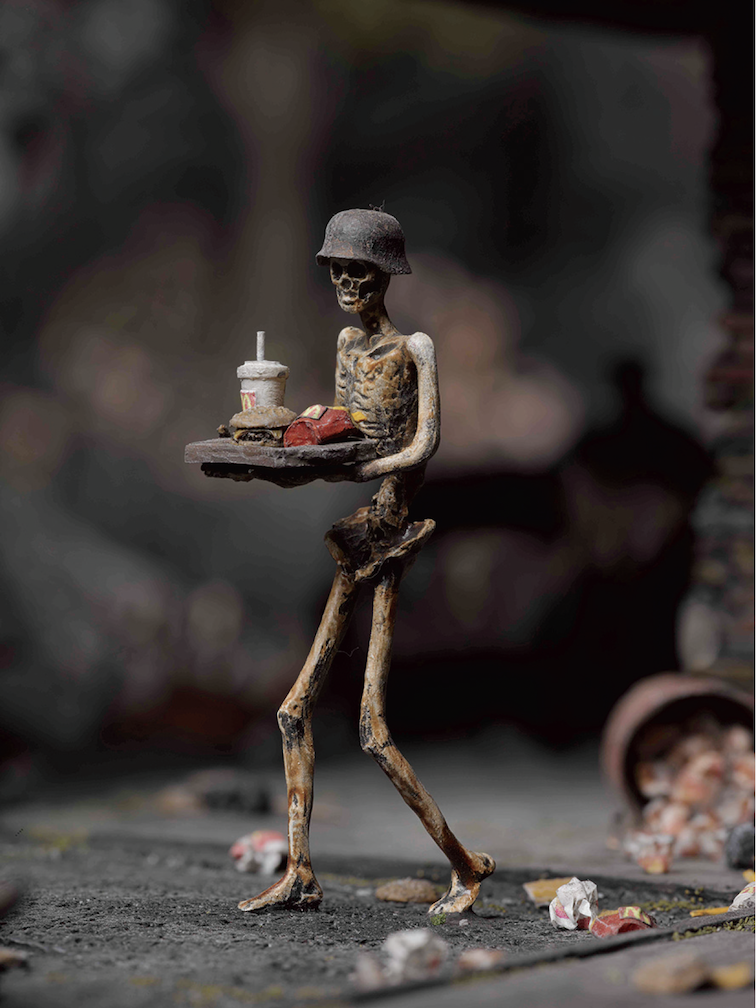

Jake and Dinos Chapman, When the world ends, there’ll be no more air. That’s why it’s important to pollute the air now. Before it’s too late. After the end of the world, also, all the technological advances which have been made in this century, which could at this very moment allow a leisure society for all but a few technicians, and a few women with wombs,—so that there will, I mean there could, be no more social class—after the end of this world when humans are no more, the machines for human paradise will run on their own. Just as McDonald’s now runs (Free Willy), 2012, fibreglass, plastic and mixed media, 80 11/16 x 50 5/16 x 50 5/16 inches. Courtesy the artists and White Cube, London. Photograph: Ben Westoby. © Jake and Dinos Chapman.

At the press tour for “Come and See” at DHC, the artists reveal that the exhibition is positioned on repetition that works toward exhaustion. They certainly achieve this much: the exhibition offers ad nauseam variation on the themes of death, sex, consumerism and perhaps less sensationally, on that of seeing and blindness, so that when you finish the grand tour you are very tired indeed. Georges Bataille largely underpins everything the Chapmans do and “Come and See” is, among other things, a latticed discussion on Bataille’s system of economy, which he saw balanced on the principles of absorption and expulsion. As the Chapmans illustrate, there is indeed a lewd “in and out” in our modern cultural and economic systems, and moreover there is increasingly disequilibrium in a hyper-commodified world, where desire and the dollar sign fornicate in an orgy of excess. “Excess,” or the “moral summit,” says Bataille, “brings about a maximum of tragic intensity.” Whereas, “the decline—corresponding to moments of exhaustion and fatigue—gives all value to concerns for preserving and enriching the individual. From it comes rules of morality.” Voici the formula for understanding “Come and See,” and perhaps all things Chapman: the artists provide the intensity, which leads to fatigue, and we insert the morality. Furthermore, the Chapmans claim that it is the viewer’s penchant for moral readings that redeems a work of art, and allows for an elliptical recycling of acts of atrocity and violence. This incessant theorizing of things, which suggests that morality is for “the rest of us” and reduces the world to idea, is tiresome business too.

Kino Klub, 2013. Courtesy DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art, Montreal. Photograph: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Repetition and exhaustion also describe the nature of conversations surrounding the work of the Chapmans, which generally focuses on its shock value from the point of the media, countered by an equally fatiguing rhetoric on the part of the artists. Here, I would have to agree with the artists. I do not find the work shocking and given the appropriation of the adjective by the media world which offers us no shortage of cheap thrills, I would imagine the brothers have little interest in competing with the twerks and tweets of 21st-century popular culture. Rather, I would offer that “Come and See” is a philosophically-based revisionist project, which turns the concept of recycling (perhaps the ultimate optimistic gesture our gluttonous moment has to offer) into an aggressive act. Victorian portraits are overpainted to shatter the crystallization of immortality by revealing sinew and bone beneath hitherto porcelain-like flesh, and Goya’s Disasters of War are, according to the brothers, “rectified” through the addition of clown and puppy heads on prints made from original Goya plates. This is rightfully considered an act of desecration, which points to the reverence we have for the finality of a work of art and how text is, in a sense, more resistant to this kind of demarcation. If an original famous literary text were physically altered through the addition or erasure of words, the gesture would be classified primarily as scandalous and secondly as “artistic,” rather than literary. Art, it seems, is the official default receptacle (trash bin) for a defined spectrum of transgressive acts, and the Chapmans push on the boundaries of that container with their specific lexicon of hijinks.

“Come and See,” 2014, installation view, DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Courtesy DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photograph: Richard-Max Tremblay.

In Flogging a Dead Horse: The Life and Works of Jake and Dinos Chapman, which takes a tremendous degree of fortitude to read, the Chapman brothers claim to have a paradoxical goal of achieving failure, or that failure is inherent in the art product, and it is this vain seeking of perfection or at least adequacy that invites further art making. With an interest in finger pointing at various strains of social illness bred by various commodified systems, the art market being just one, the effort is indeed paradoxical. Jake and Dinos Chapman are among the few elite artists who make up the major cogs of the very machine they disparage. Furthermore, disequilibrium in the general economy is necessary for the thriving of an art-based one: decline on one end affords excess on the other. By mocking their own generative power, or the viewer, for that matter, they effectually bite the hand that feeds them. This is an exaggerated configuration of mechanical and biological metaphor, but both the excess and the reference to the machine and mutilated body are apt in describing most things Chapman, which use the underpinning of morality to create various versions of “Kantian machines.” Little Death Machine (Castrated, Ossified), 2006, for example, a sculptural piece with its moving parts now dismantled so that it does not destroy itself, is a humorous mechanical model of libidinal desire, itself at times rather humorous and mechanical.

With so many repetitious unrestrained gestures in “Come and See,” one can expect the din of cacophonic visual noise; it’s the very thing that elicits the exhaustion. However, within the chaos, there is an equally unnerving quiet at the core, as witnessed in the elegant pencil drawings What Really Happens To Us After We’re Dead?, 2012, which line the gallery housing the vitrines, The Sum of All Evil, 2012–2013, themselves apocalyptic little worlds that should make noise but do not, and disturb us in that absence. As we survey the miniaturized wastelands, working past the uncanny reflection of our face in the glass that divides that world from this one, we feel the beginnings of the compulsive redemptive act that seeks to fill the space with that which is not there and perhaps was never invited. ❚

“Come and See” at DHC/ART in Montreal runs from April 4 to Aug. 31, 2014.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.