Itee Pootoogook

An air of sadness hung over “Calm Weather,” a recent exhibition of drawings by the late Itee Pootoogook. The drawings themselves, executed in coloured pencil and graphite, are not sad but rather, as the title suggests, quiet and matter-of-fact depictions of everyday life in the Canadian North. Pootoogook’s subjects here ranged from landscapes and seascapes to pre-fab housing, and from hunting and fishing scenes to their (sometimes bloody) aftermath, all rendered with concision and equanimity. No, the sadness was of our own making, a sense of sorrowful regret that an artist who had achieved recognition late in life was given so few years to enjoy it. Pootoogook, who was born in 1951 in Kimmirut on southern Baffin Island and spent most of his life in Cape Dorset, died of cancer in 2014. For many years he supported himself and his family through carpentry and construction work. Despite brief ventures into stone carving and photography in the 1970s, he was able to dedicate himself to his art only in the late 1990s. In 2000 and 2001, as the Marion Scott Gallery’s Robert Kardosh reports, he chose to “refine” his skills as a student in the drawing and printmaking program at Nunavut Arctic College.

Still, recognition was slow in arriving, a fact some observers have attributed to Pootoogook’s use of photographs as his source material. For decades Inuit art was shaped by notions of “authenticity,” northern cooperatives and southern markets dictating certain “traditional” subjects delivered in a “naïve” style—unschooled and unmediated. Even when images of contemporary technologies and Western dress had become commonplace in Inuit art, Pootoogook’s photobased approach took time to reach an appreciative audience. He finally achieved success with solo shows in commercial galleries in Toronto and Vancouver in 2010 and 2011, a two-person show with Tim Zuck at the MacLaren Art Centre in Barrie in 2012, and a solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver in 2013. (“Itee Pootoogook: Buildings and Land” was a first for the Contemporary Art Gallery, which hadn’t previously shown Inuit art.) Considerable critical appreciation and curatorial interest were compressed into a brief period of time during Pootoogook’s lifetime. That interest persists, but without him.

Itee Pootoogook, Round Table Where People Sit, Chat or Eat. This table is Located About Half A Mile Away from The Community, 2012, coloured pencil and graphite on paper, 19.5 x 25.5 inches. All photos: Charles Bateman. All images courtesy of Marion Scott Gallery.

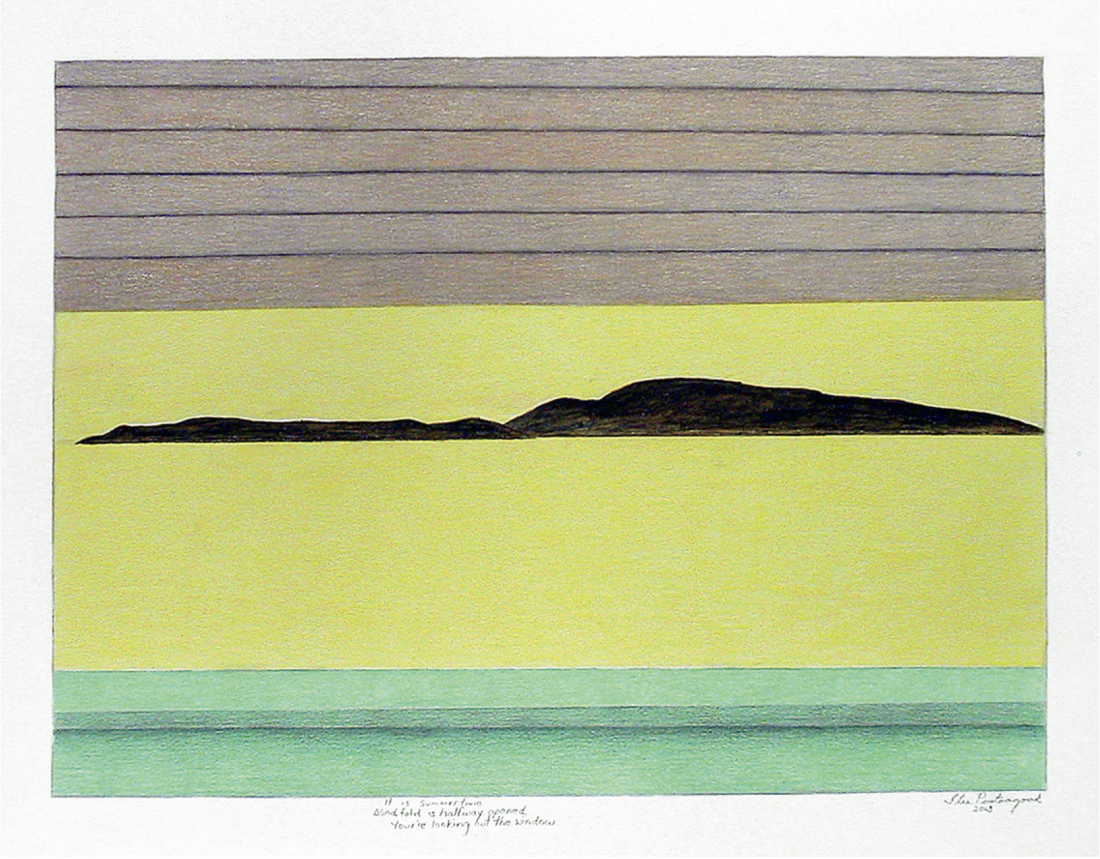

In some works, such as It Is Summertime. Blindfold is Halfway Opened. You’re Looking out the Window, the artist’s architectural subject, geometric precision and smoothly blended palette are somewhat reminiscent of early Christopher Pratt. The framing device of the window, seemingly acquired through the study of Western art history, is a recurring one in Pootoogook’s practice. Still, these likenesses are superficial—the delivery is Pootoogook’s own. Gently simplified landscape forms flattened against the picture plane, as in Gray Rock, have drawn analogies to the work of Milton Avery. However, Pootoogook brings his individual vision to bear here, along with an intense identification with the land, sea and sky, a vivid colour sense and an appreciation for northern displays of colour and light. His pumpkin orange sky fills most of Evening During Sunset; low, low down in this composition, blue-grey landforms above the cerulean blue sea articulate a horizon line.

Pootoogook’s use of graphite and coloured pencils creates a distinctive, subtly modulated surface beneath which the colour and texture of the paper are not only discernible but also integral. His drawing tools, too, allow for a particularity of detail—cracks and fissures in rocks, ripples on water, a reflection in the curving lens of a pair of wraparound sunglasses—that is faithful to his subject without being photo-realistic. Rather, these details are more linked to the intentionality of folk realism. The slightly skewed perspective employed in A Cabin Out on the Land, which depicts a small green structure with a grey roof, combines elements of the naïve and the scientific.

It Is Summertime. Blindfold is Halfway Opened. You’re Looking out the Window, 2013, coloured pencil and graphite on paper, 19.5 x 25.5 inches.

Most clearly derived from Pootoogook’s photographic sources are his compositional strategies, including a shallow depth of field and a lens-based approach to catching and framing his images. An example is Cutting Whale. Fresh Fallen Snow on Beach and Sea Water During Fall, in which two women in the middle ground regard a small, slaughtered whale; in the foreground, we see the only the greyish-black jacket and blue-jeaned legs of a man holding what may be a knife. His head remains outside the frame, amplifying the impact of the work. (Pootoogook’s depictions of dead animals, including walruses, seabirds and fish, are both attentive and matter-of-fact, as seems natural to a people who still derive much of their sustenance from hunting and fishing.)

One of the most engaging images in the show is also one of the most unexpected. Round Table Where People Sit, Chat or Eat. This table Is Located About Half A Mile Away from The Community depicts a circular picnic table with attached benches on a metal stand, dusted with snow and deserted at this moment. It’s the kind of cast concrete or fibreglass picnic table that those of us living in cities in southern Canada would expect to encounter in a provincial campground or national park during the summer months, but regard with surprise in the context of a Baffin Island winter. Set in a wide white landscape speckled with grey rocks, this object compels our interest, as it did Pootoogook’s. There is something about the presence of the solid, pre-fab forms in contrast to the wintry northern landscape, something about the state of readiness, of there-ness, made poignant by the absence of the people who would animate the scene, that speaks eloquently to the world this artist so earnestly depicted—and then left. ❚

“Itee Pootoogook: Calm Weather” was exhibited at Marion Scott Gallery and Kardosh Projects, Vancouver, from March 18 to April 15, 2017.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.