“Inuit Modern”

The words Inuit and Modern are likely to strike many people as inconsistent, yet an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario bears this title and there is no contradiction here. Tracing historic transformations in Arctic art and life, “Inuit Modern” includes work by 75 artists spanning the period 1900 to the present.

By juxtaposing old and brand new works, “Inuit Modern” convincingly argues that Inuit art has continuously, powerfully evolved. From among the whites and blacks of the rawest materials—antler, bone, ivory and stone—thrust strong bursts of colour that characterize Inuit drawing and wall hangings. This bold confluence of palettes serves as a constant reminder: Inuit art has never shied away from contradiction, or the new. Generation by generation, these artists adopted new materials and invented new forms, and they powerfully renewed traditional mythologies to meet contemporary questions.

Past the rounded, simplified forms of Dancing Bear, 1973, a sculpture by Pauta Saila, hangs a graphite drawing dominated by straight lines and right angles. These two pieces make a revealing duet. The drawing is Woman in Window, 2009, by Itee Pootoogook, and it contains a different, updated language of form. Instead of rounded contours, we are faced with flat, parallel, geometric lines—the siding of a trailer.

The organic, stoic form of a stone sculpture by Latcholassie Akesuk, Bird/Man Transformation, 1973, is set against colourful recent drawings by Annie Pootoogook. In the Kitchen, 2002, depicts a woman standing in front of a refrigerator, surrounded by modern cabinetry and household items. Every detail is inscribed in coloured pencil, including the broom and dustpan, the calendar on the wall, the light switch and the open box of Corn Flakes. The calendar and its ordered blocks of time declare: this is now.

Nelson Takkiruq, Mother Delousing Child, 1992, whale bone, ivory, stone, horn, 58.8 x 35.0 x 25.2 cm. Gift of Samuel and Esther Sarick. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Lynda Jessup, professor of Native North American art at Queen’s University, correctly posits that contemporaneity was long denied to Native cultures by art galleries and museums, whose tendency was to relegate them to the distant past as the primitive ancestors of the “modern” work of Emily Carr and the Group of Seven. In the not-too-distant past, ethnographic displays positioned indigenous art solely as artifact and not as works of art.

But there is evidence of a greater awareness mounting among Canadian art galleries over the past decade. In 2002, a series of workshops was held at the AGO, a symposium entitled “On Aboriginal Representation in the Gallery.” The discussions among Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists, curators and cultural leaders were subsequently published by the Canadian Museum of Civilization. They placed emphasis on the urgent need for exhibition spaces and permanent positions for Aboriginal peoples to create their own narratives and rightfully curate their own art history. “Inuit Modern”—curated by Gerald McMaster, a Plains Cree and Blackfoot artist and author, with Ingo Hessel, curator at Toronto’s Museum of Inuit Art—is a continuation of this earlier long conversation.

Three online panel discussions featuring many of the artists accompanied the opening. A full-day event was held with participants being Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, curators and artists, discussing Inuit art, both its history and future. (Recordings of these discussion sessions are available on the AGO’s website.)

In the exhibition catalogue, curator Gerald McMaster tackles the controversial issue of modernity for Inuit art through what he calls the “two dynamic lenses of colonial influence and agency,” making clear that devastating colonial impacts exist alongside independent choices, creativity and ultimate resilience. This duality is evident in Inuit works that address alienation and darker social issues, as well as in works that reference the continuity of spirituality in Inuit life.

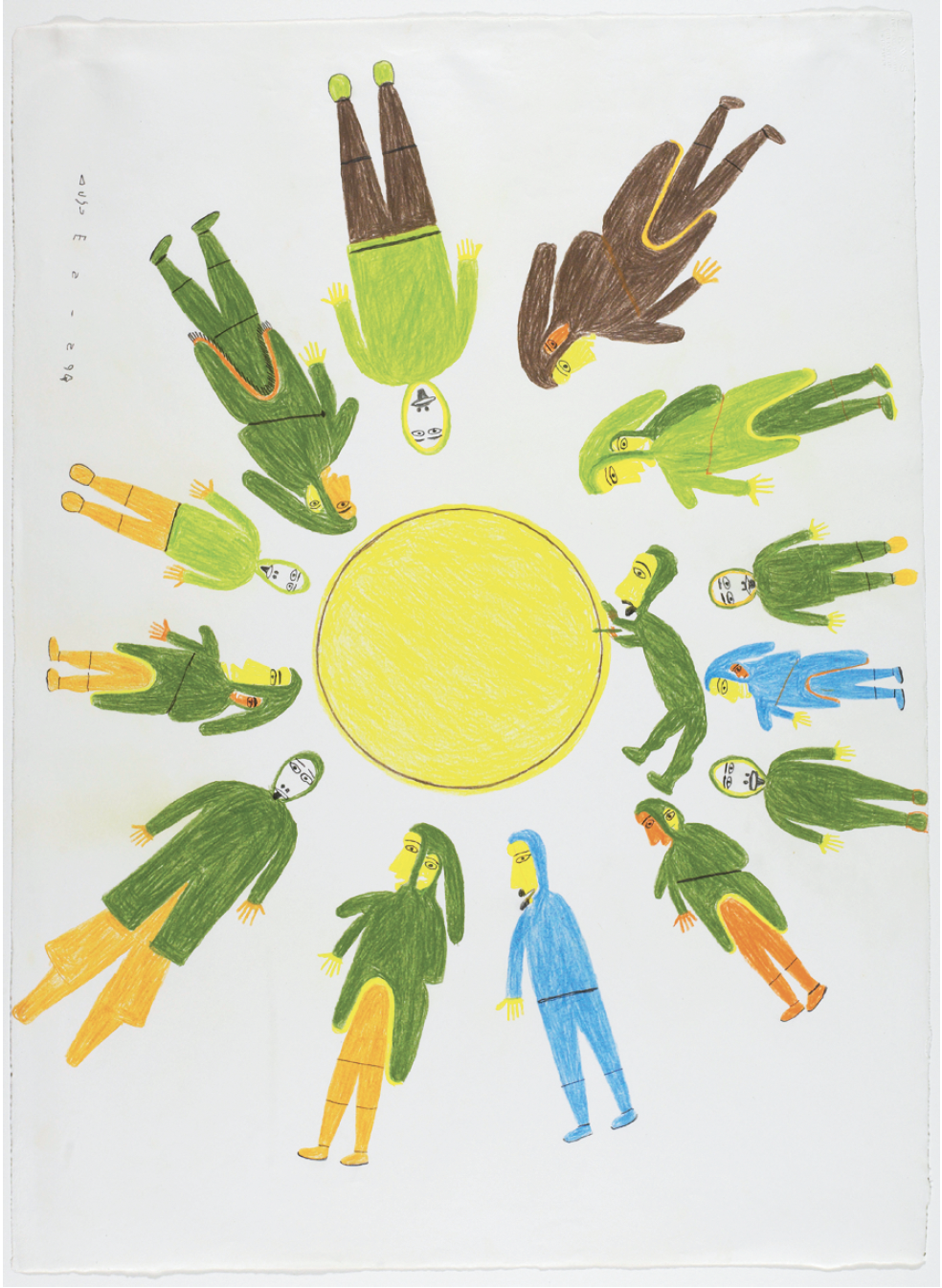

Luke Anguhadluq, Drum Dance, date unknown, coloured pencil and graphite on wove paper, 79.9 x 58.3 cm. Gift of Samuel and Esther Sarick. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Sedna on Cross, 2006, a sleek, dark stone sculpture by Bill Nasogaluak, depicts the crucifixion of an Inuit sea goddess, whose fingers are said to be seals, walrus and whales hunted by Inuit. Prayed to by hunters for her goodwill in supplying food, Sedna represents both living off the land and the Inuit mythology of transformation. Pulled out of the water and nailed to a colonial religious symbol, she is no longer able to provide. A myth of abundance is rewritten by the artist to address the present: it is a new myth now, a myth of suffering.

In Pudlo Pudlat’s drawing Spirit Embracing Settlement, 1978-79, the face of a mythic creature extends a womb-like enclosure over the trailers, power lines and inhabitants of a modern Inuit settlement. The rays of bright, coloured pencil are protective, a shield, a force field; they work to reassure that tradition survives despite new forms and challenges. The spirit embracing the settlement is adaptable, as Inuit art is itself; with a great imaginative reach, it embraces and interrogates two civilizations in constant, and often too quiet, collision.

Mainstream interest in indigenous art is expanding, with large international exhibitions on the horizon, a significant increase in the number of Aboriginal curators, and greater institutional support. Critical exhibitions include “Stop(the)Gap/Mind(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion,” 2011, in Adelaide, Australia, and “Close Encounters: The Next 500 Years” in Winnipeg, both contemporary art exhibitions with Aboriginal curators. Annie Pootoogook, an Inuit artist featured in “Inuit Modern,” exhibited her work at Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany, in 2007, at the 2007 Montreal Biennale, Art Basel and The Power Plant in Toronto. As well, in 2006 she won the prestigious Sobey Art Award.

Concurrent with the positive changes, the effects of the colonial era continue to persist as Nunavut must deal with extreme poverty, high unemployment rates, crowded living conditions, homes needing major repairs, low education levels, low average incomes, a higher suicide rate than the general national population, and high costs of delivery for public services. The boom in corporate interest in the resource-rich Arctic remains a constant threat to communities, and land claims continue to be contested. “Inuit Modern” successfully brings into focus the complexities of contemporary Inuit life while providing a platform for discussion among Inuit artists, curators and the public and is a strong example of how provocative curating can illuminate not just the present but the past. And maybe, the art argues, we have reason to hope it will illuminate the future for Inuit artists, people and all Canadians. ❚

“Inuit Modern” was exhibited from April 2 to October 16, 2011, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Anna Kovler is a writer and artist living in Guelph, Ontario.