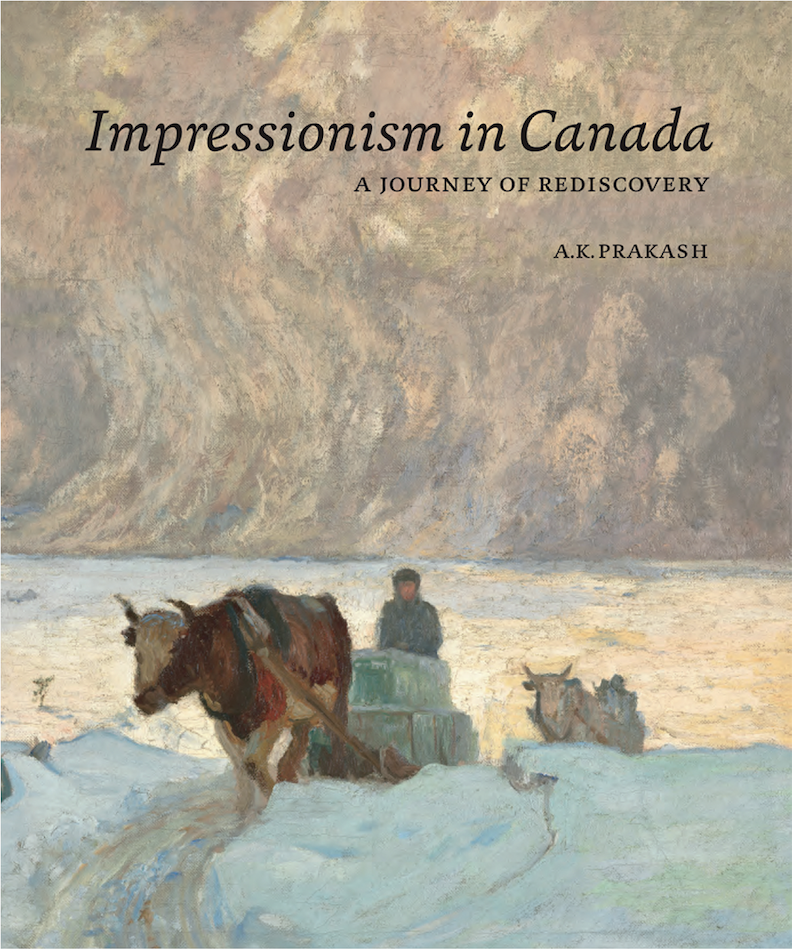

Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery by AK Prakash

Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery by AK Prakash, Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2014.

Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery by AK Prakash presents the most comprehensive survey to date of one important but neglected movement in Canadian art history. Impressionism provided Canadian artists (who began studying in Europe en masse beginning in the 1870s) with their first direct encounter of modern art as a living, breathing entity. That Impressionism proved popular in Canada into the 1920s renders the general lack of attention it has received from Canadian art historiography surprising, and pleading the correction Prakash provides.

The author occupies a unique, if not entirely impartial perspective. While not a trained art historian, Prakash has written a number of other books on related subjects, most notably Independent Spirit: Early Canadian Women Artists, 2008. He has been a champion of Canadian historical art for three decades and continues to support initiatives that raise its international profile, such as the recent Tom Thomson, Group of Seven and Emily Carr exhibitions at London’s esteemed Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Prakash is also quite possibly the most trusted éminence grise in the Canadian art world since Douglas Duncan. He is the top advisor to this country’s private collecting elite, among whom he also numbers. Whether or not Prakash was motivated to write Impressionism in Canada for solely scholarly reasons, one can’t help but speculate on the extent to which this extravagantly illustrated, bountifully appendicized, 800-page antidote to any national inferiority complex will not only rediscover the value of Canadian Impressionism, but help to confer it as well.

Aside from some forgivable awkwardness—William H Gerdts’s introduction, while interesting, adds little to the conversation, and the acknowledgements are plunked disruptively between pages 31 and 35—Impressionism in Canada is thoroughly researched, well cited and accessibly written. Its greatest achievement is the consolidation and synthesis of an existing but hitherto widely dispersed body of information. Prakash does bring a number of new facts to light, most notably the identities of the eight canvases by Renoir, Monet, Pissarro and Sisley that made up Canada’s first French Impressionist exhibition, held in Montreal in 1892. Today, every single one of these paintings, we learn with dismay, resides outside the country and/or in private hands.

Turning to the book’s title, the author is, of course, well aware that none of the original French Impressionists ever set foot in this country. Nonetheless, while points of origin don’t migrate, ideas and practices do, making the expression “Impressionism in Canada,” like “Democracy in Canada” or “McLuhanism in France,” perfectly legitimate. It should also be added that Prakash’s study envelopes the likes of JW Morrice, Helen McNicoll and a number of other Canadian artists who spent considerable time outside of the country.

Semantic clarifications aside, the title Impressionism in Canada remains somewhat misleading. Readers will discover, for instance, that Prakash has little interest in isolating impressionist practices in Canada from the rest of the world. A quarter of the book discusses stylistic migration—that is, Impressionism coming to Canada: the routes of its gradual spread to this country via France and, in some cases, the United States. Finally arriving in Canada on page 173 we are let in only gradually, first introduced to the early dealers, collectors, galleries, critics, and patrons who supported the movement and its practitioners in this country, before gaining access to more than 20 artist biographies beginning on page 262.

While thwarted expectations can often be confusing, Impressionism in Canada rewards patience. Prakash has good reason to tack an extended prequel onto his main narrative. Extant monographic studies on Impressionism in this country have tended to rush the international backstory. In contrast, Prakash represents Canadian artists, critics, gallerists and patrons as acting, adapting and contributing on an international stage, resulting in a more nuanced and engaged perspective.

Prakash’s committed internationalism does not prevent him from observing, with others before, certain distinctive features of Canadian Impressionism. He notes, for instance, a shared reluctance especially among the first generation (e.g. William Brymner, William Blair Bruce, George Reid, Franklin Brownell) to “relinquish the defined drawing, carefully modelled forms and structured compositions” of their academic training. Such emphasis on designo, while absent from most French canvases, features prominently in the work of some American Impressionists as well.

Fixation on unpopulated or agrarian landscapes is a second and more distinguishing aspect of Canadian Impressionism. Whereas a host of multinationals following the lead of the French originators was captivated by the artificiality of Haussmannized Paris—“the thousand luminous points shining through the branches of the trees” described by Italian author Edmondo De Amicis—Canadians rarely strayed from natural light at home or abroad, preferring “nostalgic views of a way of life that was passing rather than contemporary scenes of the industrializing world around them.” The determined lack of interest among Canadian Impressionists for urban and industrial subjects is fascinating. Prakash does not provide a definitive explanation, but he does point the reader in the direction of one.

The earliest patrons and collectors of Canadian Impressionism emerged primarily from Montreal’s industrial business class, specifically the notoriously unscrupulous and laxly regulated domain of transcontinental railway development. Prakash does not temper his analogy: “Like the quattrocentro Florentine merchants of Renaissance Italy, these merchant princes controlled the largest share of the country’s wealth.” For tycoons like George Drummond and William Van Horne, art functioned as a means to confirm a pre-existing, optimistic and largely fictional view of the world. Scenes of the nation as a bucolic reserve of natural resources, as a land unmolested by the populations that modernity would need to exploit or displace, point to the massive role a very small number of moneyed tastemakers played in determining what Canadian Impressionists could paint to make a living.

Impressionism in Canada is not a polemical book, and indeed Prakash’s primary goal, in addition to providing a commendable description of interrelations between global and Canadian art worlds as they existed, is connoisseurial: to celebrate aesthetic achievement. The sheer volume of information contained in the book makes it an invaluable future resource for those pursuing a wide range of research initiatives on Canadian Impressionism. ❚

Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery by AK Prakash, Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2014, 802 pages, $95.00.

Andrew Kear is Curator of Historical Canadian Art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.