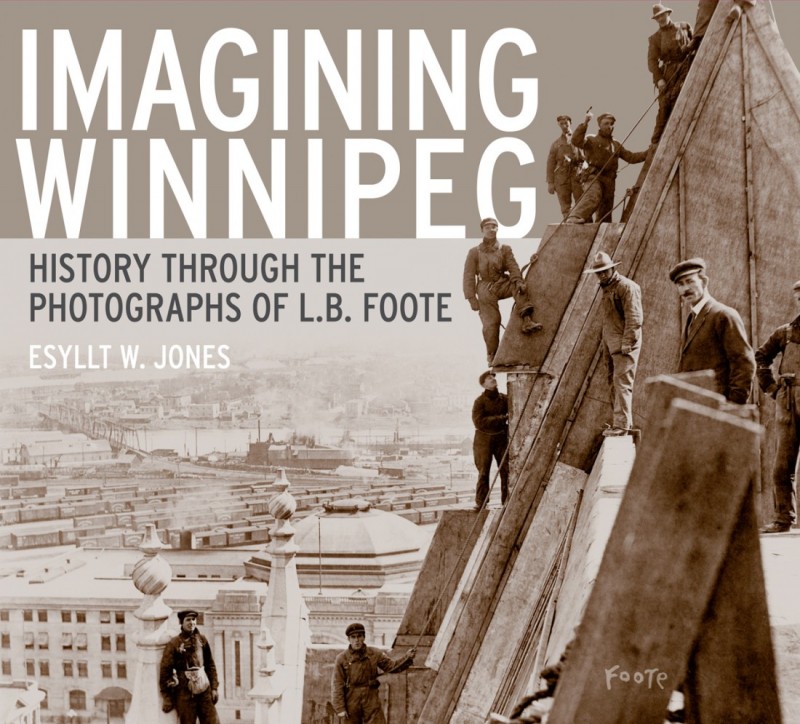

“Imagining Winnipeg: History Through the Photographs of L.B. Foote”

Whenever I approach a book in which photographs are recruited to some illustrative purpose, I do so with a mild sense of trepidation that in most cases proves well-founded. The poor, innocent photograph in its simplest form is a mute, meaningless object, subject to use and abuse by any and all: politicians and propagandists, advertisers and artists, the media and perhaps, especially, curators and historians. The unmanipulated photograph’s relentlessly democratic eye, its frustratingly stubborn insistence upon rendering everything with equal neutrality make it a true tabula rasa, as tempting to any seeking proof of a point as a blank wall is to a Banksy.

Imagining Winnipeg: History Through the Photographs of L.B. Foote, by University of Manitoba history professor Esyllt Jones, comes then as a pleasant surprise, for while no less inclined to exploit photographs than others, Jones’s approach to examining the work of Winnipeg photographer Lewis Benjamin Foote (1873–1957) is refreshingly open and honest. Unlike many, she makes a point of recognizing the open-endedness of photographic reading, she repeatedly alludes to the afterlife potential inherent in all photographs, the uniqueness of each relationship between viewer and viewed and the consequent multiplicity of evolving meanings that may accrue.

Foote came to Winnipeg in the first decade of the 20th century and worked there as a photographer until 1947. His studio and practice were little different from those in most North American cities and towns of the time. In Montreal there was the long-lived Notman studio, in Toronto there was William James and even Saskatoon had its Ted and Harry Charmbury. As photographers they served the needs of their communities, providing what Jones describes as “commercial products of consumer capitalism.” By and large, they were not artists but journeymen, and few had pretensions to be anything else. Taken as a whole, their bodies of work seldom exhibit any obvious or consistent aesthetic distinction, and based on the images presented in Jones’s book, in this regard there is little to differentiate Foote’s photographs from those of his compatriots. Jones herself makes no such claim; instead, as one would expect of a historian having particular interests in Winnipeg and working class movements, she focuses upon ways Foote’s photographs reflect the city and occasionally have come to represent it. She does, however, posit his collection as being, in some way, special. What specialness there is resides in Foote’s images being profoundly local, in their having a consistent, direct association with a particular place, at a particular time, over an extended period.

This “localness” is not something Jones addresses directly, although she does implicitly acknowledge it when she writes that many of us have seen Foote photographs, something unlikely to be true for residents much beyond Manitoba, or perhaps even Winnipeg. The same statement shows too that in writing her essay, she saw herself as addressing a primarily local audience. This, I suggest, is a far too modest assumption, for while the book certainly does contain many photographs, it is much more than just a book of photographs. Neither is it exclusively a book about a photographer or photography in general nor, despite its title, is it even primarily a history. Rather, it is a hybrid that attempts, and to a large extent, succeeds, in being all of these. That said, the greater part of the book is taken up by photographs, 150 of them selected from the Foote collection of more than 2,000 held in the Archives of Manitoba. These are prefaced by an introductory essay in which Jones conjoins a brief overview of Winnipeg’s formative years with a discussion of Foote’s career, his photographs and their relevance to the city’s history. Threaded throughout is a leitmotif of content and form that encourages questions about how histories come to be, and most especially, the problematics of using photographs as historical referents.

Arctic Ice Company employees “testing the water” on the Red River, with the University of Manitoba in the background, 1929. N1703.

The title, Imagining Winnipeg, is well considered, for how else but through imagination can one speculate upon an historical overview drawn from so few images? Like most imaginations filtered through education and experience, Jones’s has hardened into belief; in her case, one that sees Winnipeg as having been shaped by a colonialist imperative: racially white, primarily British and ideologically capitalist. Jones takes a similar stance in her examination of the relationship of photography to the economic and social development of the times and makes clear that she well understands the degree to which Foote’s images reflect the views of a particular social class. As a commercial photographer, Foote almost exclusively photographed objects or events deemed by his clients to be sufficiently significant to warrant the commissioning of a visual record; if history is indeed written by winners, then the winners in this case were those who could afford to hire a photographer. As Jones points out, even when Foote’s photographs do highlight, for example, the poor, new immigrants or Aboriginal peoples, the images were unlikely to have been made at their behest but at those who could pay.

Overall, Jones must be applauded for her selection of images; the full range and diversity of Foote’s output seems well represented. Adequately reproduced and laid out in roughly chronological order, the photographs progress in a narrative arc that, in keeping with Jones’s view of its having been a pivotal event, culminates mid-volume with eight of Foote’s by now iconic images of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. Not that there aren’t puzzling omissions and contradictions; some photographs to which she devotes considerable discursive attention are frustratingly absent. So too, her reading of individual images may well raise eyebrows since in some, interpretation seems more wishful than grounded. Curiously though, this works to advantage, compelling a more critical examination of Foote’s information-packed photographs and thereby encouraging a greater dialogue with both images and ideas.

Imagining Winnipeg: History Through the Photographs of L.B. Foote is a thoroughly engaging book and due not just to the images, because unless you’re from Winnipeg or just plain love photographs in and of themselves, only a few are especially arresting. Nor is it due entirely to the text, which, articulate and erudite though it is, offers no dramatic revelations about either Winnipeg’s history or Foote’s photographs. Brought together as they are here, though, an engrossing, inter-textual Ping-Pong plays out. Photographs, Jones reminds us, are not and cannot be history; they can only inform the imaginative act of creating it.

Imagining Winnipeg: History through the Photographs of L.B. Foote, by Esyllt W. Jones, University of Manitoba Press, 2012. 173 pages.

Richard Holden is a photographer who lives in Winnipeg.