Ikwe

With the screening of Ikwe last May at the Convention Centre Cinema, the National Film Board’s Prairie Studio launched the most ambitious project it has ever undertaken: a four-part, made-for-television dramatic series called Daughters of the Country.

The $2.4 million production cost, miniscule by Hollywood standards, was gigantic by local ones, and represented such a big chunk of the total NFB production budget for this region that several other projects were shunted aside while Daughters was in the works.

So far, in marketing terms, the investment seems to be paying off. Even before the launch, the series had been sold to television networks in China, South Korea, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei and South America. In Canada, Superchannel broadcast the series over the summer. The only chink in the series’ armour is that two crucial networks, the CBC and PBS, have not yet been secured.

Daughters attempts nothing less than a kind of fictionalized re-creation of the history of Metis women in western Canada. Each of the hour-long films is a step in a chronological progression: Ikwe takes place in 1770, Mistress Madeleine in 1850, Places Not Our Own in 1929, The Wake in the 1980s. Whereas most accounts of Metis history have centred on the irresistibly tragi-pathetic figure of Louis Riel, Daughters expressly avoids any mention of particular historical characters. All its characters are invented. They are plausible, though—people like them might have existed. The series gives a shape and voice to the anonymous Metis women whose remarkable lives were never recorded by any historian.

The entire series was produced by Winnipeg filmmaker Norma Bailey, who also directed Ikwe and The Wake. Except for editing Alan Kroeker’s adaptation of the W.D. Valgardson short story, “Capital,” she has been a documentary filmmaker. Through a long association with the Prairie Studio, she has directed a number of films dealing peripherally with native people (Bush Pilot: Reflections on a Canadian Myth, Rice Harvest, Nose and Tina) as well as one (It’s Hard to Get It Here) specifically on the subject of Indians trying to adapt to city life. Daughters is an extension of this interest in aboriginals, but it is also a venture into story-telling and conscious myth-making, new territory for Bailey.

For the contemporary myth-maker there is no medium which is at once better and worse than television. TV offers the only possibility of reaching the kind of broad audience that a national myth, by definition, ought to have. It is the closest thing we have to the fire around which people gathered to hear the stories that make up any nation’s collective memory. But it is also a jaded, trivialized medium, the primary vehicle for the current and dominant pseudo-myth of consumerism. Serious drama on TV is an oxymoron, a straw in the wind of hundreds of high-tech commercials and sardonic situation comedies. A series like Daughters, without crashing cars, machine-gun killings, aliens and snappy one-liners, is not slick entertainment. With these “deficiencies,” it’s unlikely ever to achieve a mass audience. Still, there are precedents, both abroad and at home (I’m thinking of films like The Flame Trees of Thika, A Town Called Alice or even Anne of Green Gables), which indicate that drama with some integrity and artistic merit can achieve a sizeable viewership.

Daughters does have integrity and merit. Cinematographer Ian Elkin’s pictures are brilliant and clear. He beautifully renders the Manitoba landscape in shots where trader canoes cross the lake at sunset (Ikwe) or where York boats land at the Hudson’s Bay Company post (Mistress Madeleine). The series has good pictures and it has good writing as well. Sandra Birdsell’s script in Places Not Our Own shows the hallmarks of her poetic-realistic short-story style; crude as her characters and situations may sometimes be, they are also lyrical and fully human. There are moments of inspired direction; in Ikwe the Scottish fur-trader ignorantly interrupts his Indian wife just at the point where the mother is about to tell their daughter a traditional story which would teach the girl about her Indian origins. He presents her with a blonde-haired doll.

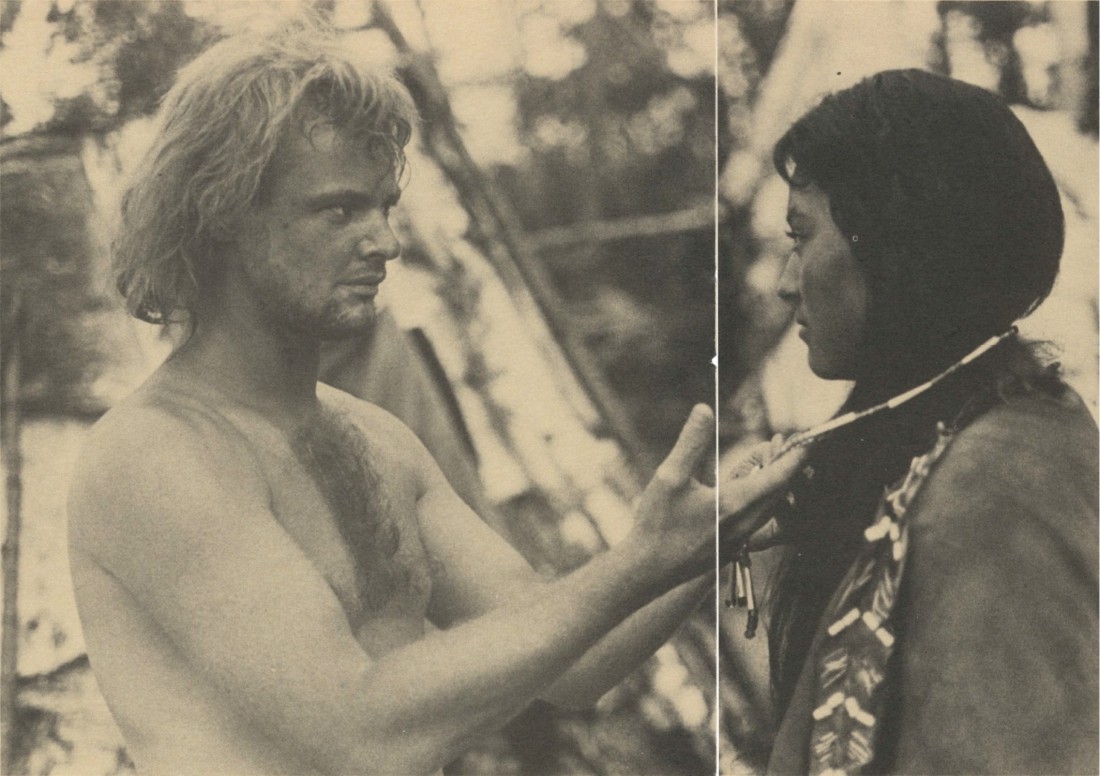

Some of the acting performances are excellent. Geraint Wyn-Davies as the young Scot in Ikwe is variously bemused, homesick, greedy and cold-hearted. He plays his part with such authenticity that it poses a dilemma for the audience: you don’t know whether to despise him for his stubborn refusal to appreciate that the Ojibway culture is a wise adaptation to the natural environment, or to sympathize with him as he tearfully mumbles nursery songs to himself while trying to last out his first Canadian winter in a tipi.

Ikwe, photograph by Robert Barrow.

Tantoo Cardinal and Dianne Debassige, who teamed successfully as mother and daughter in Anne Wheeler’s feature, Loyalties, are quite wonderful again in Places Not Our Own. Cardinal is the unrealistically hopeful Flora, Debassige is the young girl whose experience teaches her that she will never be truly accepted by white society. Debassige, a 14-year-old with a disarming smile and a precocious confidence in front of the camera, is already an accomplished actress. She is capable of outbursts of surprising passion, as in the chilling howl of despair she utters upon the realization of the loss of her friends in The Wake.

Bailey, well known for her patience, has also managed to extract some extraordinary moments from amateur actors. The cursing white kids in the school yard (The Wake) put on such a nasty display of racist, sexist behaviour that it almost seems too natural. In the same film, an altercation between warring factions in a high-school girls’ washroom has just the right atmosphere of envy and animal tension.

Inexperience, however, is inevitably also a liability, and the awkwardness of some of the minor actors in each film is an annoying reminder that, in Canada, or at least in Manitoba, we are still obliged to make do, to be content with less than the best. In Ikwe, this extends even to the central role, in which Hazel King, despite her pretty face, is rather mute and woodenly passive opposite the expressive Wyn-Davies.

There are other difficulties: the music in Ikwe, intended to convey an atmosphere of menace and dread, is overdone and obtrusive; the mad woman in Mistress Madeleine floats in and out of the narrative without finding her proper place; Debassige’s boyfriend in Places Not Our Own, ostensibly a tough rapscallion, actually seems as though he might have grown up in River Heights; and The Wake has such an abundance of characters and situations that they seem crowded and jostled in the one-hour time frame.

As mythology, Daughters operates on two levels. One, as already mentioned, concerns native people. The other has to do with the respective roles of the sexes. While the women are admirable, redolent with moral courage, flawed only in that they are too trusting, the men (i.e., the white men) are gutless, treacherous and thoroughly contemptible. Each of these films has a principal male character who is less a cruel brute than a spineless coward. These men, when exposed, prove to be no more than whimpering little boys, unworthy of their women. This is “herstory” with a vengeance.

Granted that, considering the treatment they have been given in fiction and film in the past, women have every right to revenge, the fact remains that the artistic result is one of oversimplification, of good gals vs. bad guys. This undermines the basic premise of these stories: that the Metis bridge two worlds, bringing together the spirit of two peoples. If the character of one of those peoples is merely weak and loathsome, how can the outcome be a proud new nation?

There is also a degree of self-flagellation in the repetitive depiction of native people as the victims of white oppression. This is not to argue the truth of such a depiction—it was, and continues to be, an indisputable fact. But whose fact is it to tell? While it’s true that bringing racial injustice to light is the responsibility of anyone aware of it, regardless of their own race, there is something disturbing in the fact that all the creative control—writing, direction, production—in an important new series about native people is in the hands of non-natives. Is Daughters a way of exorcizing white guilt?

There are a number of questions raised when one culture fictionalizes another. One is historical and cultural accuracy: some native people who watched Ikwe, for example, observed that it would have been inappropriate for the title character to relate to her grandmother her prophetic dream of the coming of the white man. The telling of such dreams was understood to be the prerogative of elders. But accuracy is not the crux of the matter. (In fact, Daughters was painstakingly researched.) Some native people in the premiere audience found the fur trader’s use of the word “savage” objectionable. It is obviously the word that such a man in such a place and time would have used; but a native filmmaker might have decided on a different word, or, for that matter, on an entirely different story.

The re-created history in Daughters of the Country constitutes a story integral to a full understanding of western Canada, but it is still not the native version. White society has grown accustomed to Indian silence. Because the silence makes us nervous and uncomfortable, we are compelled to speak, to fill the void. But our expressions, however valid, should not be mistaken for the native interpretation of events. Daughters of the Country, while firmly taking the side of native people, is a substitute myth. I hope its existence will not retard the depiction, in film, of the native peoples’ own national myth. ♦

Ralph Friesen is a regular film reviewer for Border Crossings.