iCuba! Art and History from 1868 to Today

Christopher Columbus stated upon arriving on the shores of Cuba in 1492 that it was the most beautiful land human eyes had ever beheld. Charmed by its exotic flora and fauna, he claimed this beauty for Spain, which maintained its power over the island for more than 400 years. Now the Musée des beaux-arts de Montreal lays claim to evidence of Cuba’s complicated beauty and history in the form of more than 400 works of art in an exhibition entitled “¡Cuba! Art and History from 1868 to Today.”

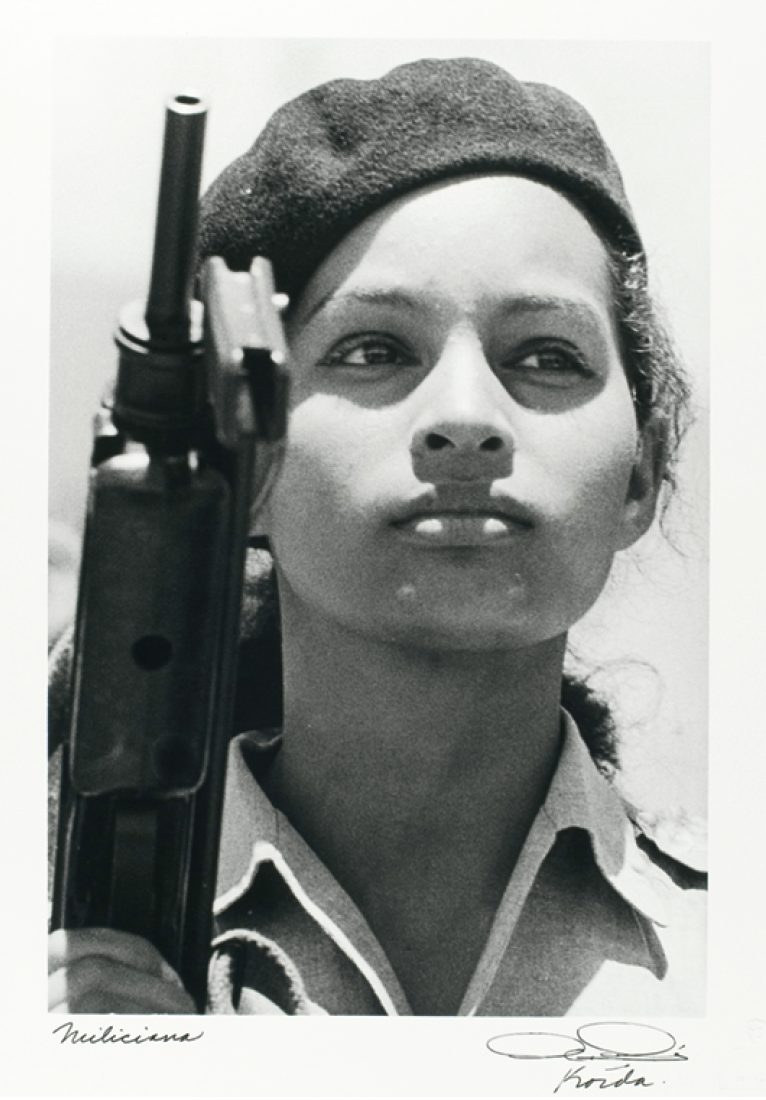

Alberto Korda, Militia Woman, Havana, c. 1962, gelatin silver print, 35.6 x 27.9 cm. Collection of Diana Diaz. Courtesy: Couturier Gallery, Los Angeles. © Estate of Korda/SODRAC (2007). Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

According to curator Nathalie Bondil, the theme of the island and insularity is central to the exhibition. She states, “Insularism brings a physical awareness of the limits of one’s territory and at the same time an awareness of the immensity of the world.” At various times in history, for many Cubans the notion of the island likely brought on an acute, if not desperate, awareness of the physically small yet immense distance between here and there, such as described in a quote from Virgilio Piñera’s La isla en peso, 1943: “This damned circumstance of water everywhere / compels me to sit down at a table in a café. / If I didn’t think that water had me surrounded like a cancer / I’d be able to sleep at night like a log.”

Insularism has its effects not only on the insider, but the outsider as well. For as much as we know of Cuba’s complex history, it is still a place of mystery and of varied and wide interpretation, a place upon which it is impossible to look with any kind of neutrality. Therefore, viewing the show, it is easy to find one’s self searching for political or philosophical subtext, although Ms Bondil emphasizes that this was not intended as a political show.

Anonymous, Marlon Brando playing the conga, Havana. With him, the Cuban author Guillermo Cabrera Infante, 1956, gelatin silver print, 24.1 x 19.4 cm. Vicki Gold Levi Collection, New York.

Beginning with 1868, the year in which Cubans in the town of Bayamo first declared independence from Spain, the exhibition is divided into five sections: “Depicting Cuba: Finding Ways to Express a Nation (1868–1927)”; “Arte Nuevo: The Avant-garde and the Re-creation of Identity (1927–1938)”; “Cubanness: Affirming a Cuban Style (1938–1959)”; “Within the Revolution, Everything, Against the Revolution, Nothing (1959–1979)”; “The Revolution and Me: The Individual Within History (1980–2007).”

Not each section carries equal significance, with the preliminary section consisting largely of landscape painting and portraiture, which hold more historical than artistic value. However, these canvases lead us through the historical narrative of the exhibition until the moment in which photography takes over this role. The photographs, some never seen outside Cuba, and some iconic, such as those by Korda, Salas, Corrales and Noval, are truly among the most noteworthy works in the show. Also impressive are the Pop art-style propaganda posters supporting the Revolution (Castro finding Soviet art “cold”). In support of his stylistic tolerance, he is quoted as having said, “Our enemies are capitalism and imperialism, not abstract art.” It is these portrayals of the artistically tolerant Castro that left me seeking mention of him as persecutor of intellectuals, writers and artists. Because, as much as he may have lacked preconceived ideas of style, he certainly had preconceived ideas of content.

Raúl Corrales, Cavalry, 1960, gelatin silver print, 4 of 6, 30 x 40 cm. Collection of the artist. Courtesy: Couturier Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

The headliner of the show from a curatorial standpoint is Wilfredo Lam, whose work is given its own room. He was born in 1902 to a father of Chinese descent and an Afro-Cuban mother. His father, being quite elderly, died shortly after Lam’s birth and the artist grew up with stronger associations to his Afro-Cuban roots. In 1923 he went to Europe to further his studies in art and in the 1930s met André Breton and Picasso. It was the use of African imagery that attracted Picasso to his work and he encouraged Lam to develop this style, reasoning that his African descent authenticated his use of this imagery. His works do evidence Surrealist influence, but more obvious is the impact of Picasso. Interestingly enough, the star of the Montreal exhibition had refused to participate in the 1944 show, “Modern Painters of Cuba,” held at MOMA, unwilling to be labelled a regional painter.

Jorge Arche, Portrait of Mary, 1938, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 76.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana. Photo: Rodolfo Martinez.

Also given special attention is Cuba colectiva, the 1967 Salon de Mai mural, which, other than for a very brief period of exposition in Paris (withdrawn due to the student uprising of 1968), had never been seen outside Cuba. Held for the first time in the Americas, in Havana, the Salon de Mai was called “a contagious happening in the land of merry socialism.” This large mural, whose central theme was the Revolution, was the collective work of 100 European and Cuban artists, writers and poets. Lam conceived of the idea and divided the panels into 100 numbered sections for which the artists drew lots. Castro was invited but never arrived so the section allotted to him remains empty. The execution of the piece is indeed a little rough, its strength residing primarily as evidence of one magical night of communal art making.

Wifredo Lam, The Murmur, 1943, oil on paper mounted on canvas, 105 x 84 cm. Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de creation industrielle. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Donation to the French State, 1985. © Estate of Wifredo Lam/SODRAC (2007).

It is in the section dedicated to contemporary art that we see the subversive, the ironic and the humorous. There are many strong installation works, such as El bloqueo (The Blockade), 1989, by Tonel, in which the words of the title and a geographic map of Cuba are fashioned out of cement blocks. There are also two excellent pieces by the once trio, now duo, Los Carpinteros. Also noteworthy and more international in theme is the final installation in the show by Carlos Garaicoa. Entitled Now Let’s Play Disappear (ii), 2002, it consists of a large table holding replicas of the world’s most famous buildings, fashioned out of small burning candles projected onto a video screen via closed circuit. It is a beautiful and contemplative piece and it is a shame that, leaving its ethereal light, you are thrust into the bright light and reality of the bookstore. It would be nice to linger in that quiet moment and consider the artist’s questioning of mankind’s act of self-extinguishment.

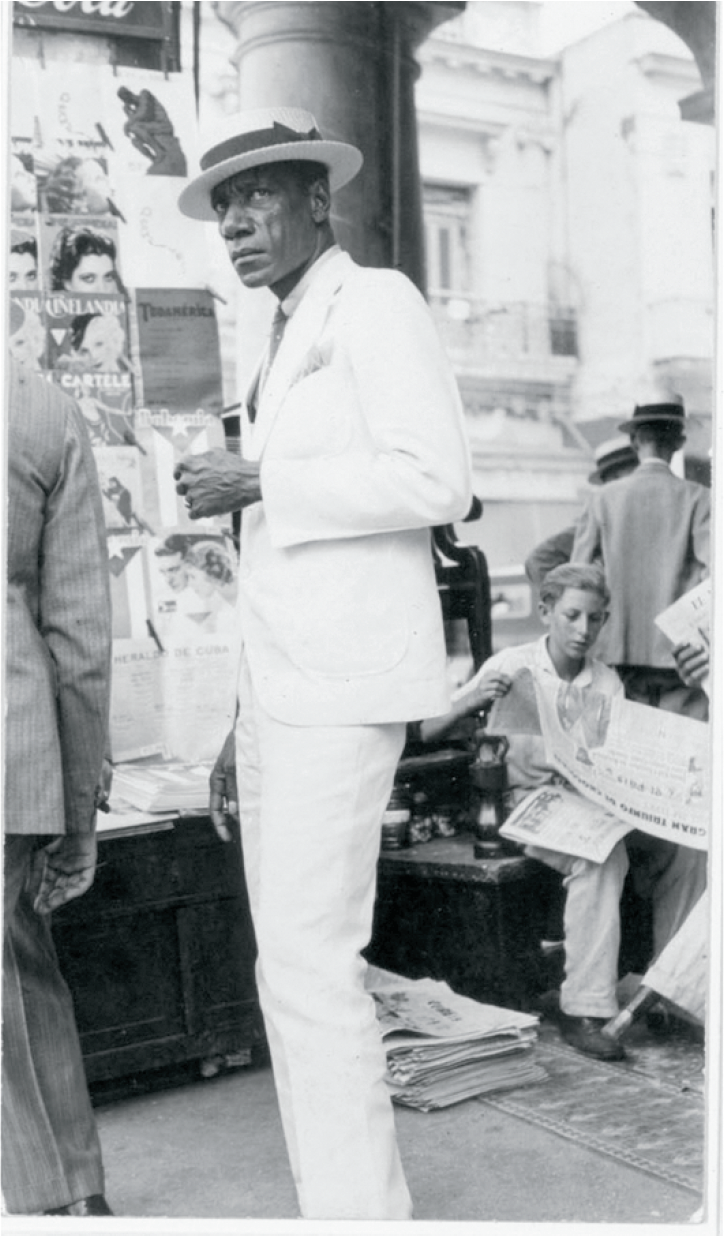

Walker Evans, Havana Citizen, 1933, gelatin silver print, 24 x 13.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1952. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image © 2004 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“¡Cuba! Art and History from 1868 to Today” is ultimately a show focused on Cuban identity, which, of course, is understood as part of the curatorial definition, but can also be seen as its limitation. I was curious about the many excellent Cuban artists potentially excluded from the exhibition on the basis that they were not making identity-based art. There is also a lingering curiosity about the current state of censorship in Cuba. Although we know that Cuban art has definitely found its place in the international art market, little is known of the artists’ present-day circumstances. The subject of censorship is better addressed in the sizable catalogue than in the show itself. Although there are examples of subversive or ironic art, there is little curatorial comment on the status of the artist throughout the different periods and perhaps there could have been a more visible tribute to the artists who were the subject of persecution. However, this ambitious exhibition gives visitors an opportunity to see a substantial amount of work that is otherwise inaccessible outside Cuba and it makes strides in breaking stereotypes of this small, yet complex, country. ■

“¡Cuba! Art and History from 1868 to Today,” curated by Nathalie Bondil, was exhibited at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montreal from January 31 to June 8, 2008.

Tracy Valcourt writes and studies in Montreal.