Ian August: How to Make a Painting

Ian August, Window Curtain, 2022, oil on canvas, 91 × 120 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

If painting were a recipe, then this is how Ian August would make one. Take an idea, add two cups of research, put on your flaneur apron and mix in a requisite number of walked miles, add a cup of photography, another cup and a half of model making, repeat photography, with a touch of abstraction. Mix together with just the right amount of heat for just the right amount of time and take out of the studio. Place in a gallery and call it a painting.

Ian August, Merkato, 2020, oil on canvas, 76 × 61 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

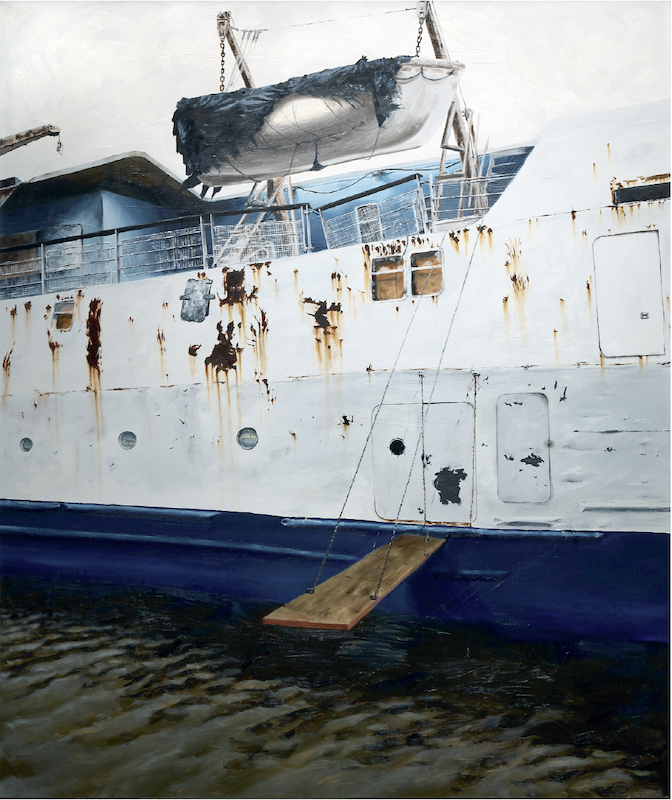

August is a kind of vernacular utopian who has made paintings about an unusual range of subjects, from soap pumps—what he considers “the quintessential object of our time”—to replicas of the objects looted from the National Museum in Baghdad during the Iraq War in 2003; from views of what windows look like from the outside, to perspectives on a room in a Toronto office tower designed by Mies van der Rohe. He has painted the largest of the boats that took tourists up and down the Red River. When he renders the Paddlewheel Queen, he makes it an unstoppable icebreaker; in Lord Selkirk in the Slough, 2009, his version of the decommissioned Lord Selkirk, a ship that ventured as far as Lake Winnipeg on overnight excursions, the vessel’s rusted sides, frayed lifeboat cover and empty loading ramp are sad remnants of faded luxury. He places the elaborate silver sauce boat owned by Lord Selkirk on a wooden dining table in Fort William during the vice-regal’s illegal occupation of that settlement. August, who is Métis on his mother’s side, has made his cultural ancestry a component part of his sculpture and painting.

Ian August, Rooster Town Kettle, 2020, stainless steel, paint, 7.01 × 3.05 × 4.88 metres. Photo: Aaron Cohen. Courtesy the artist.

August’s subjects can be both personal (his summer employment was working as a riverboat tour guide) and public (he was outraged by the images of an American tank crew watching the looting that resulted in 15,000 antiquities being stolen from one of the world’s greatest museums). What all his projects have in common is that he wants the objects he paints to occupy the category of the serious and the sincere. “I always try to honour the object,” he says. “It might be made out of a goofy part, or it might contain an aspect that pokes fun at itself, but the thing is usually self-aware enough to know that even if it’s got those flaws, it can still be proud.” August takes seriously all the contributing art forms he employs, but he takes pleasure in playing inside that seriousness. When Mies insists that his room in the Toronto office tower remain unchanged, August views that as an opportunity to “mess a little with modernism’s paternalism.” The framing of the photographs he took to document the room undermines Mies’s claim for spatial immortality, but he follows that mischief by including scrupulously made miniature copies of the Barcelona chairs and the Riopelle painting that are still in the room. There is a small irony to his downscaling. August has said he has always wanted to be an abstract painter, and that while he has tried to become one, the attempt has never been successful: “I have to figure out ways to trick my process into allowing bits of abstraction to happen.” In the small Riopelle he found one trick: “I guess with that one I finally got into abstract painting.”

Ian August, Fetching Water, 2020, stainless steel, paint, 157.48 × 182.88 × 2.54 centimetres. Photo: Liz Tran. City of Winnipeg Public Art Collection. Courtesy the artist and Winnipeg Arts Council.

The series where the goofy quotient comes into play most conspicuously is the “Soap Pumps.” A series will come about when he feels an idea can be self-generating: “It starts to do that cyclone thing where the objects relate to one another and it builds from there.” The soap pump idea originated because of the object’s ubiquity, a presence that dramatically increased during COVID when handwashing became an obsessive activity. When he calls it his “little series that I keep doing in the background of everything else,” he should have his mouth washed out with the content of one of his soap pumps.

Ian August, Lord Selkirk’s occupation of Fort William, 2018, oil on canvas, 122 × 122 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

A number of them are acrylic on paper, a medium and surface that allow him considerable flexibility. “I can work on a piece one week and then come back to it later on,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll try to complete one in a single sitting. But they are something I always have on the go.” August admits that the strangest thing about this series is that he and his wife now have a large collection that they have broken down into categories: things like the weird, the seasonal and “bathroom decorative.” August initially thought he would have to make up the weirdest ones, but it turned out that those actually exist: “I can come up with pumps on my own, but the ones that are found are just too strange.” He has invented some—a high heel pump that moves in the direction of the fetish, and a Sicilian pump that came out of watching season two of the White Lotus TV series, during which decapitated head sculptures repeatedly turned up in the resort hotels.

Ian August, excavation number: Kh.IV 452 Dupe, 2015, found plaster, buttons, rope, Melmac dish, iPhone case, 26 × 16 × 16 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

Ian August, excavation number: Kh.IV 452, 2015, oil on canvas, 122 × 122 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

For the “Window Series” he returned to his practice of being a flaneur who takes photographs in the street. He is adverse to using Google as a way of providing source material; he insists that his images be found in the same way that his sculptures have to be handmade. His challenge in the photos is to decide how much wall he needs to frame the window, which is already a frame. In Coconut Garden and Sunlight Market, he goes to small, independent stores, picks a cropped corner of a window and makes that incomplete perspective the subject of the painting. In Gelyn’s Wedding Lounge he presents the window as a view into a green, exotic and ultimately unknowable world. Window Curtain, 2022, picks up a subject he has been trying to include in his work for 10 years. “A plant is another thing I would like to be,” he says. Window Curtain shows the leaves and flowers of a jungle scene on a pair of curtains—“I put them on the window as an excuse to paint the plants.”

Ian August, Soap Pump 52, 2017, acrylic on paper, 32 × 25 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

Ian August, Soap Pump 13, 2016, acrylic on paper, 33 × 22 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

Ian August, Soap Pump 22, 2017, acrylic on paper, 30 × 24 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

Ian August, Soap Pump 65, 2018, acrylic on paper, 30 × 24 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

August is also a sculptor, and he has made a number of captivating public sculptures. His most successful is the Rooster Town Kettle, 2020, a massive 23 x 10 x 16-foot painted stainless-steel kettle that commemorates a Métis community of 59 families situated on Winnipeg’s southwest fringe. The entire community was bulldozed in 1960 to make way for commercial and urban development. The newspaper campaign mounted to portray the people living in Rooster Town as unhealthy and dangerous was startlingly racist. To counter that history, August focused on the tradition of welcome that occurred in every Métis home: you were offered tea from water boiled in a copper kettle, always on the wood stove. For him, the kettle was the symbol of Métis hospitality. Based on a United Nations Resolution, he calculated what amount would provide boiled water on a daily basis for the 250 people in the community. His kettle is large enough to hold that amount of water.

Ian August, Lord Selkirk in the Slough, 2009, oil on canvas, 183 × 153 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

It is characteristic of his own range that his sculptural production would include a silver sauce boat and a copper tea kettle. One was made as a model for a painting and the other was a stand-alone public sculpture. He says, “By making the objects I know them and by painting them I know them even better.” Because August’s practice is so various, he is able to move easily from one medium to another. Any of the component parts of his aesthetic cookbook hold on their own, but he admits that painting is the key to his artistic practice. “I feel like I have an obligation to be making paintings, and I feel guilty if I’m not producing them. I enjoy doing sculpture but I feel that the medium needs painting to legitimize it. The simple truth is painting is the art form I like the most.” ❚

Ian August, Icebreakers on the Red, 2009, oil on canvas, 115 × 155 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.