Hunky Dory

Alexis L Grisé and Jen Funk

Drawing—a rudimentary technique. Ground zero of art. The origin of all possibilities. A line is an inscription of time, which in historically oriented cultures is itself conceived as a straight line onto which events are progressively strung, a timeline. “Time may change me, but I can’t trace time,” David Bowie sings in “Changes,” a song from his fourth studio album, Hunky Dory—an album that provided the inspiration for a recent collaborative show by the Winnipeg-based artists and lifelong friends Jen Funk and Alexis L. Grisé. In their ambition to express the experience of inevitable change, Funk and Grisé use freestyle drawing and frottage (which can be understood as a kind of automatic drawing), respectively. In both iterations of the basic technique, the artists employ drawing as a kind of litmus test of transformation. While a line is always an inscription of time, whether intentional, accidental or automatic, such inscription at the same time represents a radical contraction of the complicated circumstances leading to its materialization. As an abstraction and a trace, the drawn line is never alone. Its character points back to its author, and does so doubly in a self-portrait, assuming the existence of that which produced it: a pencil, a charcoal, a pen; a hand, a body; intentions, emotions, energies. Hence, to the perceptive, a simple trace of a drawing instrument may appear as a condensation of an entire universe, and this inherent multiplicity of meaning functions to betray the line’s apparent stability. That is to say, a line is simple in its presence, and rich and complicated in its inscription.

Installation view, “Hunky Dory,” 2020, La Maison des artistes visuels francophones, Winnipeg. Courtesy the artists.

When a drawing is digitized, it necessarily loses most of its exciting accidentality in the process of conversion to clear and distinct numerical data. As the composer Georg Friedrich Haas noted after a show of his groundbreaking work at the New Music Festival in Winnipeg in 2015, when asked about the role of the computer in composing: “Somehow, the computer is always wrong.” In music, everything happens in-between and around the notes; in art, everything happens in-between and around the lines. This is why the materiality of the gallery installation of “Hunky Dory” appears to me now as charged with special significance (I was able to see the show in person back in September, in the earlier, less severe, phase of the lockdown in Winnipeg, before art exhibitions were forced to move into the digital realm). The show stood as a testimonial to the irreducible presence of artwork. Perhaps such an assessment sounds conservative, but it is a mathematical fact. As the conversion of phenomena into digital data requires compression, the loss of information (and the addition of the media-specific noise) is inevitable, and changes our experience of a work. Moreover, the digital platform not only redefines spatial orientation, it also redefines our experience of time. Our encounter with artworks in a gallery space requires a combination of sustained attention and the horizontal movement of our bodies, and our gaze, which most often travels along artworks as it would along the natural horizon. When observing art reproductions digitally, our body and eyes are more or less fixed, which further diminishes accidentality from the experience, while the screen moves rigidly in a vertical direction, since most content is subsumed to the characteristic digital gesture of scrolling.

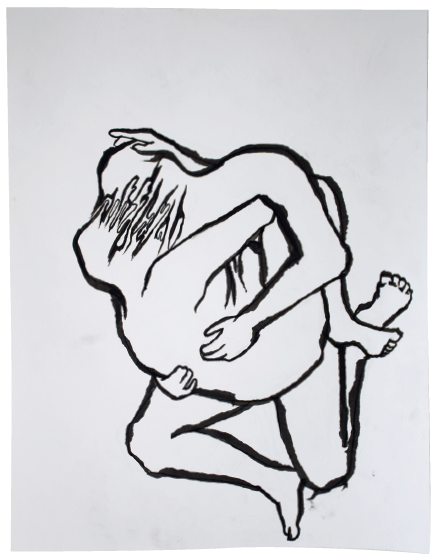

In the course of 14 drawings, linearly arranged along the eye-line across multiple walls of the gallery space—an arrangement that creates a sense of chronology—Jen Funk presents the intangible metamorphosis of her body and identity, the elusive and tentative journey of her gender transformation. In this series of manually drawn self-portraits, accidentality is ever-present in the acute instability of a style that ranges from shredded lines with a marked fragility to evident traces of erasure, which can be thought of as a form of negative drawing, and are frequently contrasted with decisive, bold ink lines. Hence, in her drawings Funk’s transformation is decisively brought to life by the struggle between positive and negative space, between definition and the indefinable. I experienced the play between the lines as a dynamic melody abounding with subliminal vibrations I could never consciously pinpoint. In one of the more powerful drawings in the series, we see two facing figures, their bodies wildly entangled and their faces melting into one another’s. The drawing draws our attention to the fact that the experience of time in the artist’s journey is acutely physical, and yet the function of her work is to instruct us about infinite pliability and the instability of physicality.

Installation view, detail, “Hunky Dory,” 2020, La Maison des artistes visuels francophones, Winnipeg. Courtesy the artists.

Pinned on the wall at the opposite side of the gallery space, Alexis L. Grisé’s large charcoal frottages present an interesting contrast to Funk’s minimal drawings. The line in his two large works is dense and heavy, hardly distinguishable as it threatens to solidify in a deep-dark surface. And yet, streams of brightness undeniably penetrate the blackness. These streams derive from imprints of the furrows of textured materials upon which the canvas was pressed. Such imprints paradoxically underscore the artist’s clever intentionality because Grisé chose materials that appear fixed yet wear down—objects with wood grains, such as telephone poles found all over the Exchange District and Chinatown in Winnipeg, where he recently relocated from New York—in order to reflect a sense of the changes and displacements in his life. As Grisé points out, his work is a celebration of entropy—an understanding of time as progression towards increasing disorder: from tree to pole to weathered pole to pulp. The artist’s frottages are hence reports on materiality, which is progressively wearing down. Through these reports, the struggle between time and its representations unfolds on many levels. Just as you can never fix entropy, change is impossible to capture in a drawing, for change happens in-between the stages we are compelled to capture. The inability to capture change itself can teach us something about the difficulty of experiencing it. It’s like aging, which always requires comparison with previous stages, with something already past. Perhaps Bowie had something similar in mind when he sang the legendary line: “Time might change me, but I can’t trace time.” ❚

“Hunky Dory” was exhibited at La Maison des artistes visuels francophones, Winnipeg, from September 3 to November 26, 2020.

Monika Vrec˘ar is a media theorist and writer living in Winnipeg.