Howard Podeswa

Howard Podeswa’s exhibition “A Brief History” begins with a single work, set apart and alone upon a wall overlooking the Koffler’s main gallery. Watching Goya’s Colossus in My Sorels, 2009, shows the artist similarly situated, upon a hill, wearing the titular big boots. A few white strokes denote the footwear’s furry fringes. From afar, he presides over a procession of pilgrims, huddled together and shuffling along, away from a mass of menacing and murky cloud. These days, it is an all-too-familiar scene of migrants on the move. Yet multiple layers of meaning—art historical, personal, biblical—vie with one another, suggesting that the artist is striving not just to witness but truly understand this journey, one identified with hopeful, urgent agency and with awful fates that may seem preordained, as when we are raised within a world of fear and hate. Looking upon Podeswa’s dark cloud, I am compelled to consider the condition of being doomed. The Coen Brothers’ film A Serious Man, 2009, explores the idea of being cursed within multiple contexts, ranging from the secular and comically absurd to the mystical and deadly serious. The movie’s final scene similarly depicts an oncoming storm that seems, at this point in the narrative, somehow a sign for the protagonist’s inevitable ruin.

And then I turn the corner and confront a small painting of a crumpled construction, a degraded and darkened bit of textile or paper. This humble picture lies at the other end of the still-life spectrum from the starched white napkin stiffly situated on the sidelines of a lavish table. For me, this thing becomes a vehicle for speculation and strain; it may be the record of a meditative exercise, perhaps while in mourning, trying and failing to find meaning following a period of profound malaise and misfortune. Untitled, 2014, does not even deserve a designation.

Howard Podeswa, Heaven, detail, 2015, oil on canvas. All photographs: Toni Hafkenscheid. All images courtesy Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto.

But then I confront the sizable Study for Hell #1, 2013, which offers a figure that is centrally placed and that seems at first welcoming, despite the title. Snappily dressed with a red coat and carrying a walking stick, this gentleman stands upon some green ground. Calming and charming in effect, he may be a Dante-inspired gatekeeper or guide through the underworld. Swirling about him, however, are machine parts, a horse and body parts that seem strung together, suggesting a shared destiny. All are only partially present, given the meteorological turmoil. Sensing a hint of hell, I then notice my host’s mouth, which may be morphing into mandibles. Darkness is descending indeed, with one individual orchestrating my downward path. But a more anxiety-inducing notion is that this swirling entity is, in fact, a preprogrammed machine, which in the next picture, Study for Hell #2, 2013, appears to be operating at full throttle. Here figures are caught up within the curves of a cataclysmic contraption, churning about in a Turner-like state. Clinging to one another—as the pilgrims did earlier—they also grasp their own bleeding and bruised bodies. All have wounds and are further surrounded by red flecks; the injuries and the pain take on independent lives, more disconcerting when placed apart from any specific actions or memories.

However, Podeswa leaves some space for absurdities within such scenes of tumult and terror. The fourth in the “Study for Hell” series, 2013, features another terrible, torrential vortex—rendered with a flurry of furious strokes—and yet contains characters which strike comic notes. A creature’s behind and legs dangle from the side of this storm while others appear quite comfortable; a skeletal servant of Lucifer crawls along the top, oblivious to gravitational (or perhaps any other) laws. A few pointy-eared creatures seem stable despite the surrounding carnage and chaos. While other figures appear to advance forward in an orderly fashion, another plummets and a skull stares upon him or her with hungry anticipation. The forces of fate may take many forms, and all may consume us; for Podeswa, they (or it) may appear from the painterly ether as humanoid (a demon), weather (a storm), galactic phenomena (a black hole) or abstract marks. The imagery is half hidden or partially portrayed, as though still emerging from, or receding back into, other realms that are cosmic and/or unconscious in nature. And yet, Podeswa consistently connects these worlds to everyday events, often drawn from ubiquitous media sources. Study for Hell #5, 2013, features a Ferris wheel, for instance, that has been transformed into another spherical spectre, a rotating device that throws passengers—those seeking mere amusement—to the four winds, over and over. Unlike the weather or black holes, this ever-spinning machine was made by humans, signalling that we may reap what we sow. Also on hand is a line of little, identical figures in black, perhaps nuns or ultra-orthodox men. I speculate that even those with the most ritualized and devout lifestyles cannot be spared the idea of damnation and doom, of eternal punishment. It is such realizations—interrupting cheerful childhood memories—which may be further expressed in this striking picture with abrupt slashes of white and grey, freed from literal descriptive purposes. And then I recall the Old Testament, telling us how Job pleaded his case to God, who shows up in the form of a whirlwind, refusing to explain the tragedies that he has suffered. Job would never understand anyway, and so why bother?

Heaven, 2015, oil on canvas, 9 x 15 feet.

Having performed a rotation myself, moving along three dark and narrow passages occupied by the Studies, I enter a central space occupied solely by two enormous paintings: Heaven, 2015, and Hell, 2013. The latter work conveys a long-term sense of accumulation—of myriad marks, applied over many, many months, potentially years. A colossal circle is centrally placed, containing a conglomeration of imagery, referring to a host of calamities, catastrophes and casualties, seemingly drawn from both nightmarish recesses of the mind and online news reports. Their fates could have been averted if humanity were more human; I detect acts of shaming prior to execution, some hands raised and bound. The carcass of an unknown creature is rendered in fragmentary fashion. Gazing at this incomplete corpus, I recall Kafka’s melding of the monstrous and absurd in “The Metamorphosis,” 1915. For Podeswa, terrors are not permitted to reach a level of literalness associated with conventional spectacles of horror. He offers me slow-burning scenes, as it were, melded together within a single frame and with surfaces—stained and scuffed, rubbed and smudged—that come across powerfully as a palimpsest, and hence as a vehicle for contemplating how the mind may deal with the notion of damnation: memories fade and yet always have the potential to return and haunt, again and again.

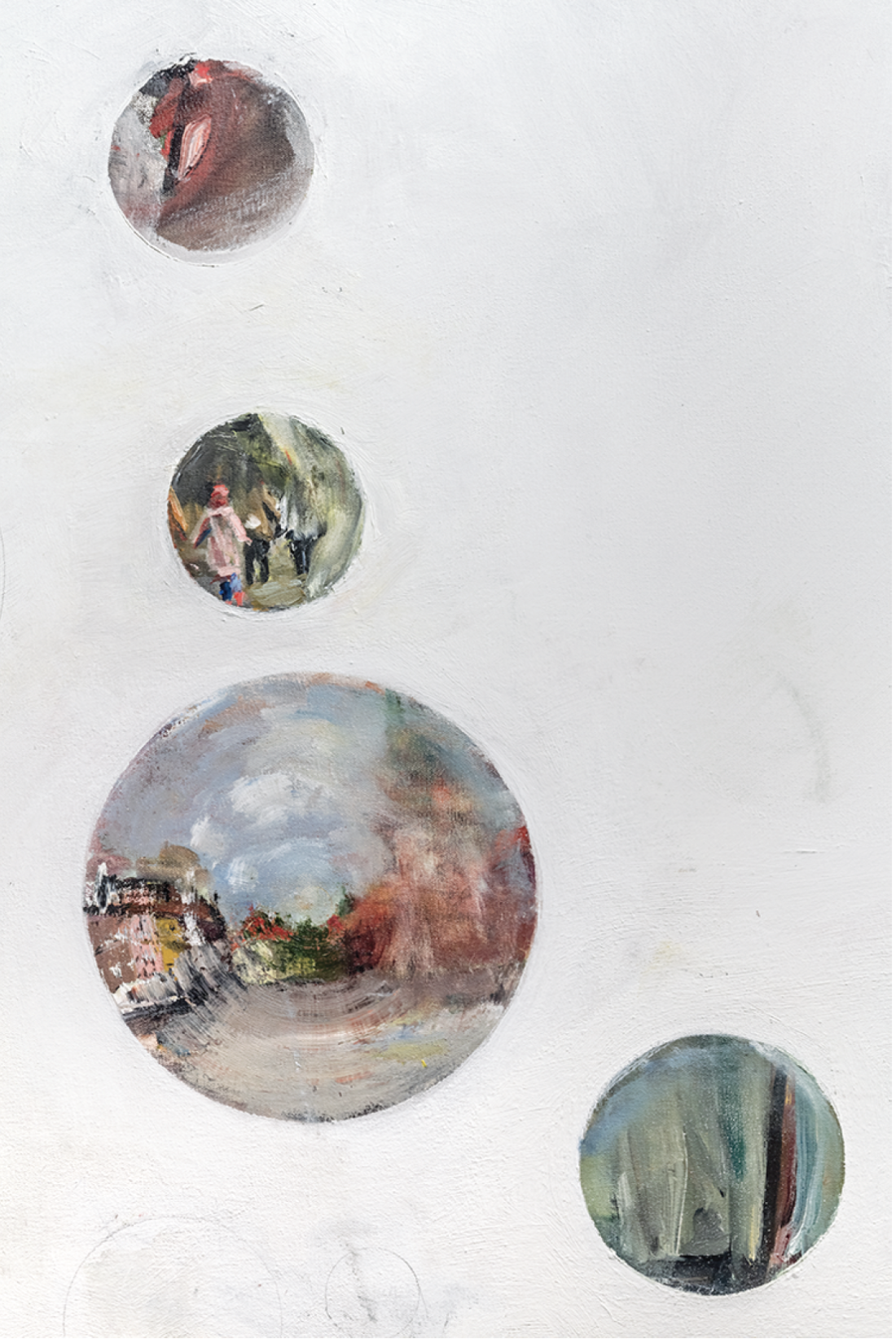

Now I turn around to confront Heaven. It offers a collection of miniature spheres, floating within a field of whiteness that, for me, with its laboriously layered surface, can come to signify the ethereal non-place and non-time of the hereafter. However, referencing the planetary, these miniature worlds could just as easily be taken for mere bubbles. And yet their sizable scale suggests otherwise: each appears inhabited by territories, terrains and potentially living inhabitants. As biospheres, each exhibits a different degree of resolution or magnification, offering surfaces that seem at turns geographical, astrological and biological, with glints of forest green and sometimes yellowish glows. They refer equally to domains that are either being created or are fading back into the dusty soup from which we all derive. While viewing this work, I am no longer mired by memories of the needlessly victimized. My outsized anxieties, for the moment, feel small, like miniscule marbles that can be carried in a pouch on my person. Gravity and oxygen and relative scale are shed, along with the most hellish thoughts: that there is no rhyme or reason to any of it, including the senseless suffering of the innocent and the good. My mind is now free to hold onto gestures, colours, shapes and textures that are also undoubtedly human and material in nature. When our brains evolve further, perhaps we will realize, without any doubt, that this is what we were meant to do all along. ❚

“A Brief History” was exhibited at the Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto, from January 14 to March 27, 2016.

Dan Adler is an associate professor of modern and contemporary art at York University.