Hilarious Horror

“I had never seen it before but I immediately felt like I knew it. I loved it and it gave me such courage in its company. I felt companioned by that vision.” Toronto artist Shary Boyle is talking about her personal connection to the work of Shuvinai Ashoona, the Cape Dorset drawer with whom she has collaborated on a drawing exhibition called “Universal Cobra” (organized by Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto and Pierre-François Ouellette Contemporain in Montreal). Their first opportunity to work together was in “Noise Ghost” at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery in 2009, an exhibition curated by Nancy Campbell. “She had the insight to see the connections between our work,” says Boyle, and those connections are even more apparent in their recent collaborative work.

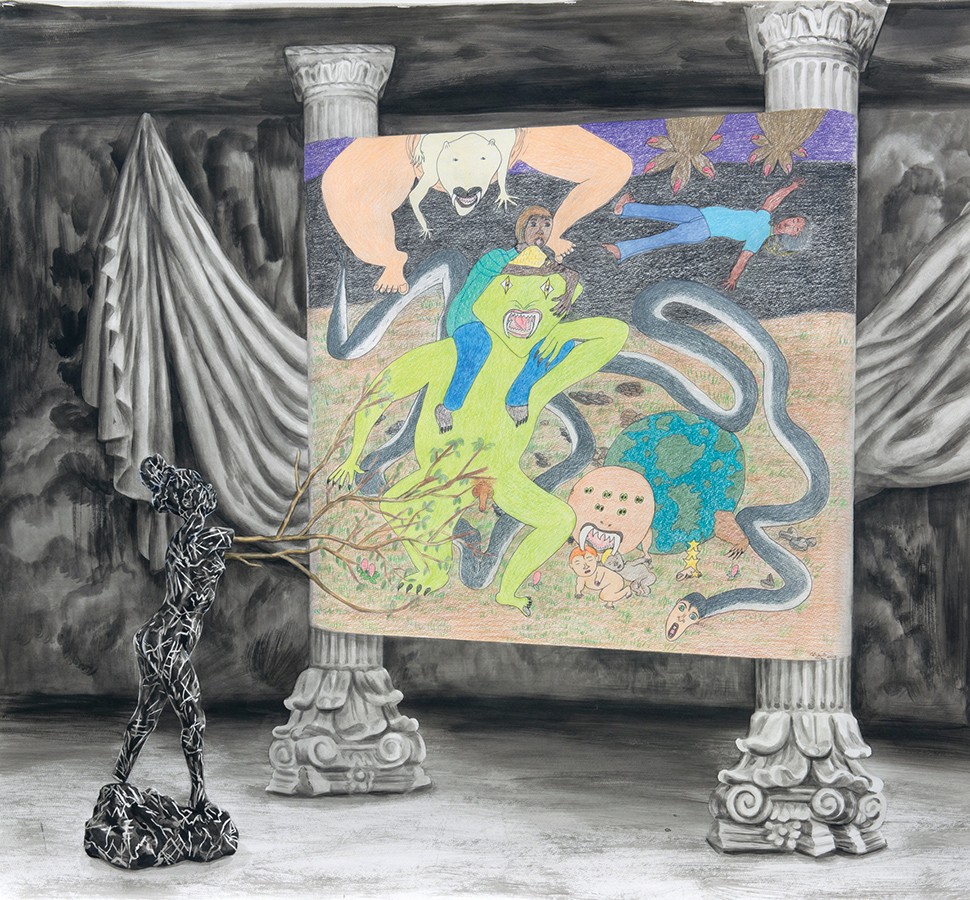

Shuvinai Ashoona + Shary Boyle, Exhibition, 2015, ink on paper and coloured pencil, 99 x 107 cm. All images courtesy Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, and Pierre-Francois Ouellette art contemporain, Montreal. All photos: Paul Litherland.

Boyle has travelled to Cape Dorset on two occasions to work with Ashoona, and over the course of those trips they have figured out a method of collaboration. For the drawings in “Universal Cobra,” each of them would start a drawing and leave unfinished areas in which the other would work. In Exhibition, Boyle drew a series of unconventional museum plinths—hands, body parts and different kinds of structures—and Shuvinai supplied the exhibition’s content, even turning the logo of the West Baffin Co-op in Cape Dorset into a modernist sculpture. It looks like a candelabra that Keith Haring could have made, with a little help from Joel Shapiro.

One of the most interesting of the drawings is Self-Portrait, in which Boyle draws herself as a cobra figure borrowed from an Egyptian pottery vase. The cobra and her polka-dotted dress are a matched ensemble. “I was mainly thinking that the lady would see herself in the drawing mirror,” says Shuvinai, “and she encouraged me to water paint her snake woman, so I did a bit on her face.” Boyle’s self-portrait has a peg leg. “I always want to throw in a handicap in the horse racing sense. There is something about the truncated limb that speaks to me of the challenges people have, and how they limp through their lives.” Boyle notes the subtlety of her collaborator’s response to the deficiency: “She cradles the end of that peg leg in a little nest of the most delicate eggs, which is such a beautiful gesture.”

Shuvinai Ashoona + Shary Boyle, Black Marble, 2015, ink on paper and coloured pencil, 91 x 107 cm.

Boyle regards their collaboration as “an amazing conversation. But it is not literal and you can’t pin it down perfectly. Sometimes it is a way to talk about things that there are no words to talk about.” The drawing that best gives voice to the unsayable is Black Marble, in which Boyle’s emblem of European art is a statue with no hands and broken feet. She proposes that her figure has been given new life through Shuvinai’s voice. Inside the frame of the painting and within her drawing, Shuvinai has imagined a world of mirthful monsters. Her motivation is simple: “I decided to draw what I had seen in a scary movie.” Boyle describes what Shuvinai achieves as a mixture of the “horrific and hilarious. The combination of those things makes her work so alive for me. She opens that tap, and look what comes out. It’s like a dream, where there is no value system between good and bad. It just is.” ❚