Hervé Guibert

Hervé Guibert’s photographs are portraits of friends and lovers, many of whom appear in his books: Thierry Jouno—i.e., T—director of IVT (International Visual Theatre) and CSCS (Centre Socio-culturel des Sourds), who likely informed Guibert’s novel Des aveugles (1985); Vincent Marmousez, the boy-love muse of Fou de Vincent (1988); the Belgian writer Eugène Savitzkaya, with whom Guibert had a decade-long exchange, collected as Lettres à Eugène: Correspondance 1977–1987, 2013. A few are unnamed, as in Le Poète, who lazily smiles up at him.

Photography, for Hervé Guibert, always hinged on a charged complicity between artist and subject. Ghost Image, 1981, his well-known tract on photography and its lack, begins with the photographer’s chasing his father away in order to carefully pose his mother; the photo-roman Suzanne et Louise, 1980, for which Guibert staged and photographed his eponymous great-aunts, sometimes in simulacrums of their death, hinges on a similar shared collusion, kept from the rest of the family. The photographic encounter is not just a moment but a pact.

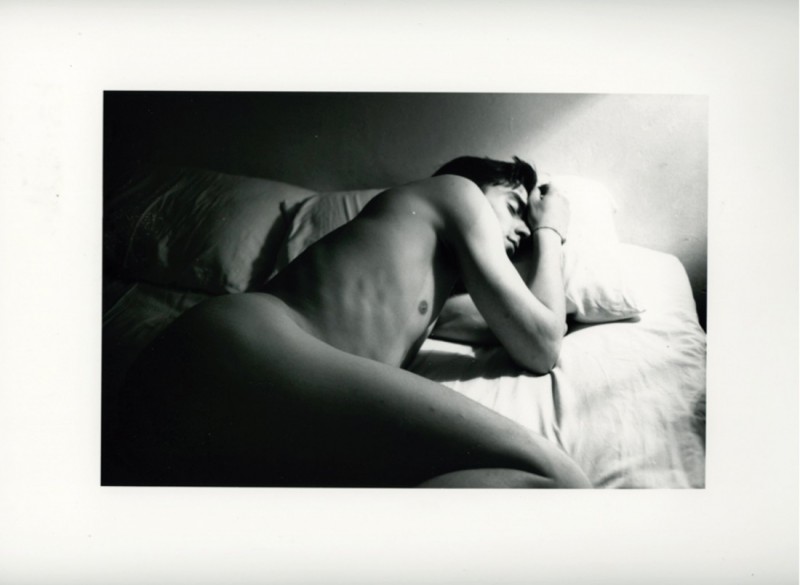

Hervé Guibert, Vincent couché, 1988, silver gelatin print, 14.3 x 21.6 centimetres, edition 3 of 25. Images courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts, New York.

Here are the facts: 15 delicate black and white photographs taken between 1976 and 1988. These years would, in retrospect, seem carefree, near halcyonic. The men depicted—young, slim, radiant—lie down, slump over, lean down, handstand. Their nudity feels incidental, not necessary. Each photo is bound to its own unequivocal experience. It’s hard not to read them as monuments.

Le Seul Visage, 1984, a slim collection of Guibert’s photographs, begins with an arresting confession: “In my writing there’s no brake on what I do, no misgivings since I’m virtually the only one who counts (other people become abstract characters bearing just initials), whereas in photography there’s the body of other people, relatives, friends, and I’m always a bit worried: am I not about to betray them by turning them in this way into visual objects?” As the only one who counts—the only one who exists on the page—he is the only one for whom there can be consequences. This accounts, in part, for the impatient cruelty, the frenetic desire to reveal all in his novels. His photographs betray his humanity.

Sometimes I think no one loved as purely, or as desperately, as Guibert loved Vincent Marmousez, the louche skateboarding junkie who monopolized his imagination. Singular obsession has its perils. As a way to pull away from what he called the “false presence” of photos, Guibert would rephotograph his photographs of Vincent, hoping that by losing a bit of the print’s precision, it would abate his longing. In Crazy for Vincent, he snarled about Vincent’s “ugly face,” redeemed only by his “beautiful torso”; he described him as a “monster,” a “leper,” a “pathetic little shit,” but he did photograph Vincent rolled over on his side, hiding the mark on his thigh of which Vincent was ashamed (Vincent couché, 1988). In Vincent de profil/carrelage, 1984, Vincent is shot in profile against white tile, his lazy eye hidden from the camera. Another shows his astonishing smile. Photos of Vincent have the candour and intimacy that orbit conversation in the moments before falling asleep. Just as the photos of photos offered Guibert the gap needed to ease Vincent’s absence, the distance of the camera might have allowed him to truly see.

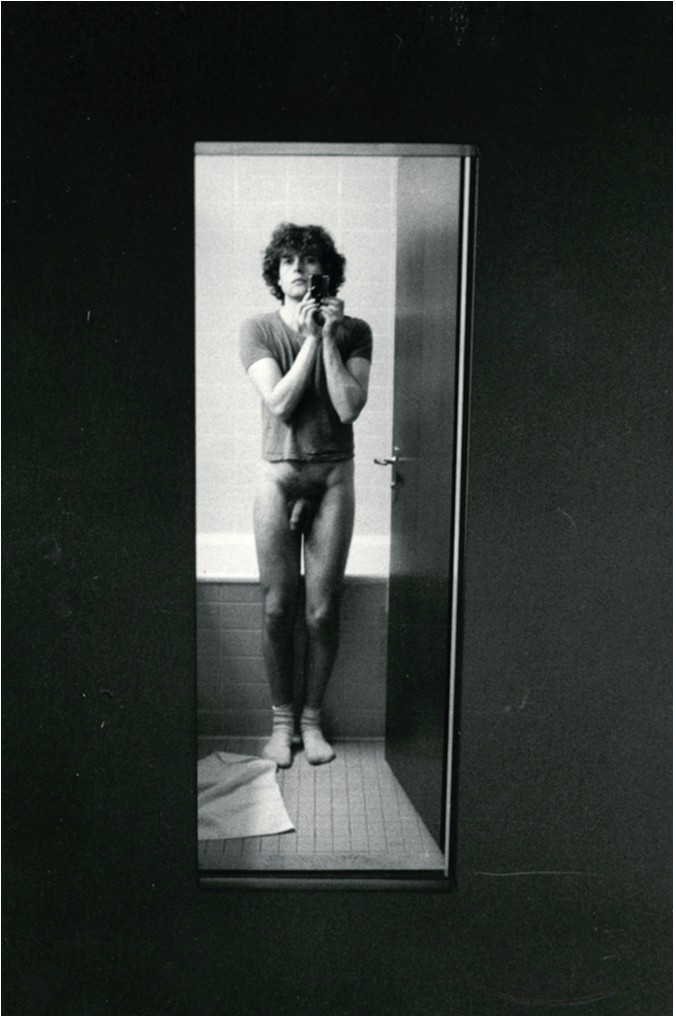

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait Nu devant glace avec Tshirt/Rollei, n.d., silver gelatin print, 22.9 x 15.2 centimetres. 60028txt.

In Autoportrait Nu devant glace avec Tshirt/Rollei, one of the two self-portraits on display, Guibert appears naked but for his socks and t-shirt, a gesture that seems sweet, unbidden, until I remember his deep shame about his concave chest, which he bitterly described as his “pigeon chest.” His anxiety about this infirmity— his “deformity,” as he would say—was a shame with which he’d play throughout his life. In Mes Parents, 1986, Guibert wrote that his life could be split in two, divided by the day when he was told by another boy, upon seeing Guibert’s chest, that he was “not like him.” This sense of alienation, this other-ness, would be a barometer for understanding all of his projects. He would place X-rays of his upper body, clearly depicting his upper torso, on the window of his sixth-floor apartment at 293 rue de Vaugirard. This provocation was a way to “display the most intimate image of myself—much more intimate than any nude.” Occasionally, he would photograph the window with the X-ray set against different objects, a macabre game of signifiers, a clue lying in plain sight.

Forget representation: back to a body entangling another. Crazy for Vincent again: “Vincent said to me, I have fungus, he said. I have scabies, he said, I have a sore, he said, I have lice, and I pulled his body close to mine.” Vincent’s ugly face and beautiful torso pressed against Hervé’s beautiful face and ugly torso.

“Hervé Guibert” was exhibited at Callicoon Fine Arts, New York, from January 6 to February 10, 2019.

Janique Vigier is a curator and writer based in New York.