Henrick Håkansson and Eadweard J. Muybridge

I was 10 years old. In late summer heat, sweat-drenched and ecstatic, I was hell-bent on chasing the neighbour’s Siamese cat through that hedge. I had the sensation, which I still remember with crystal clarity these many years later, of ploughing through a soft and crinkly paper barrier. It was a barely resistant one that tore open more like dry skin ready to peel than the ribbon at the finish line of the schoolyard 100-foot dash. The air around me was suddenly alive with a frenzied buzzing sound, a fairly horrific sound because of its deep and intensifying fury, and there were myriad yellow and black shapes streaking across the surface of my retinae. Not long after, as incoming venom from the hundreds of stingers made itself felt, I started to scream.

What do those childhood memories of the ubiquitous yellowjackets, as well as other, far more welcome, dreams of racehorses and slow molasses all have in common? I found out recently when I wandered into VOX and revisited those youthful sensations, if only vicariously, at a recent exhibition that serendipitously paired the work of two artistic savants: contemporary Swedish photographer Henrik Håkansson and 19th-century Western landscape photographer and “animal and human locomotion” expert Eadweard Muybridge.

A large screen in the middle of the space presented Håkansson’s video The Lure, 2000. It was alive with the hectic conflation of wasps and flies drawn to a sweet confection placed outside on a pole. The accompanying soundtrack of the wasps at work was excruciating in its intensity, and I suddenly, vividly and synaesthetically, relived my youthful assault by the wasps. They take no prisoners, those wasps—unlike bees, they will sting more than once—and the nails-on-blackboard buzzing soundtrack to the video installation at VOX was the perfect accompaniment to their nightmarish fervour.

Henrik Håkansson, still from The Lure, 2000, video installation. Photographs courtesy VOX, Montreal.

Håkansson works and thinks like a scientist. I’m reminded of Harold Edgerton as a worthy predecessor, as well as Muybridge in photography and Jean-Henri Fabre in entomology. Fabre was responsible for bringing insect natural history to a wide public in the 10 volumes of his Souvenirs Entomoligiques. Although Håkansson, like Fabre, had no scientific training, he is also an obsessive and passionate observer of insect behaviour. Using film, installation, sound and digital photographic modes, Håkansson has, for many years, observed, with seeming objectivity, patience and precision, the workings of the insect world. No question that he has the soul of a driven ecologist and the integrity of a latter-day Fabre—and his work reconnects us with the natural world from the perspective of an artist who cares deeply for the natural environment and its countless denizens. Indeed, his work reawakens the Boy or Girl Scout on sabbatical within us all. He does not take sides in his nature-based work but the choice of emphasis is itself a political statement of sorts. His work generates an umbrella-like aura in which the antennae of the viewer are tweaked, and tweaked again hard—as in the harrowing documentation of swarming wasps.

In another video of a bumblebee in motion (an insect innocuous in contrast with the wasp), he appreciably slows down the flight. Flight of the Bumblebee, 2002, imports the insect into our immediate visual space and, in slowing its flight down on two adjacent screens, brings it up close and personal with the optic, inducing a frisson that has an emotional impact akin to that of his work with the wasps.

Håkansson brings into the foreground of his work a nature from which humans are increasingly estranged and makes it a forum for dialogical thinking and reflection. This is precisely what he has in common with Eadweard Muybridge. Both artists used scientific methodologies to create incubators for thinking—and to make temporality into slow molasses.

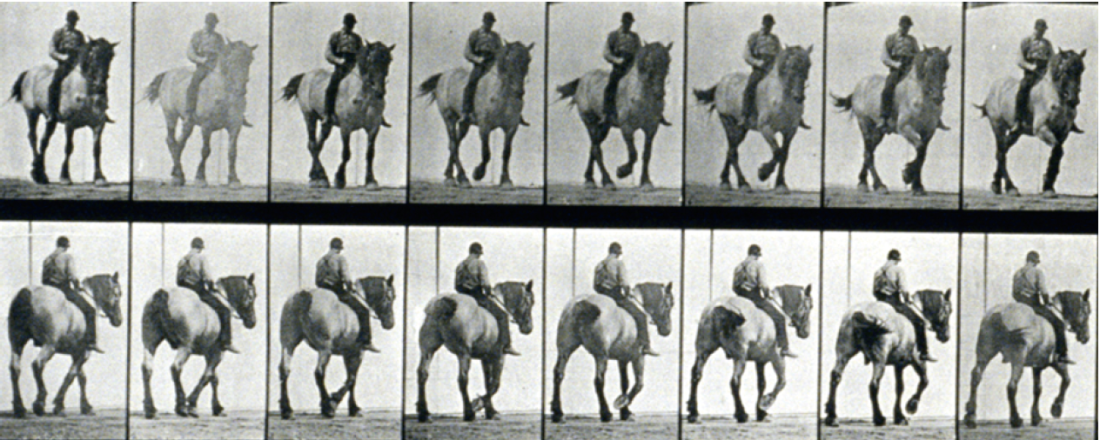

When Muybridge arrived in America in the 19th century, he became a legendary landscape photographer. A fortuitous encounter with Leland Stanford, the railway magnate and governor of California, led him further afield. Stanford was obsessed with racehorses. A possibly apocryphal anecdote relates that Stanford wanted to settle a bet as to whether a horse in full gallop always has one hoof in contact with the ground at any one moment. So he commissioned Muybridge to photograph his horse in motion. The photographer, with engineers aiding him, did just that and invented a system of multiple cameras that could document each of the horse’s movements at full gallop. Chronophotography, as it came to be known, provided thenceforth a useful instrument for the examination of human and animal locomotion. His photographs clearly demonstrated that the horse had all four legs off the ground at the same time.

Edweard Muybridge, Animal Locomotion, 1887, phototype, planche 578, 47.8 x 60.4 cm. Collection Musée d’art de Joliette.

This device, the zoopraxiscope, foretold not only Edison’s moving pictures but prefigured much that is still galvanizing in cinema today. Muybridge soon migrated from horses to humans, publishing his photographs as a portfolio, Animal Locomotion, a landmark in photographic history, in 1887.

The twelve collotype plates exhibited at VOX—loaned by the Musée d’art de Joliette—derive from this body of work. The subjects of these collotypes were often photographed wearing little or no clothing. Women walking downstairs, men boxing and so forth, all figured in Muybridge’s exhaustive taxonomy of repetitive motions.

Both photographers—one the inventor and prophet, the other a contemporary practitioner— examine antecedents to, and the implications of, “Bullet time,” which we all know is employed in recent cinematography and video games, when the temporal sequence is displayed as extremely slow or even frozen moments so that the viewer can observe faster-than-the-eye-can-see events (such as bullets in flight). Consider the recent film The Matrix. Håkansson wants to elide nature with his observations of it, with no illusions and only hard facts, inviting his viewers to reconnect and reify the natural world as our most worthy dialogical partner.

Muybridge was one of the great photographers of the natural landscape as well as an adept in keeping time in check. In the 21st century, both artists bring us closer to a Nature from which we are increasingly estranged. No less importantly, they take the gaze hostage and trigger an unprecedented collision of time and motion. As both these photographers prove, and as was abundantly clear at VOX, we may not be able to stop time altogether but there are, after all, ways and means of slowing it down. ■

“Henrik Håkansson and Eadweard J. Muybridge” was exhibited at VOX in Montreal from May 6 to June 17, 2006.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator based in Montreal. His extended study Figures and Grounds: The Work of Ross Heward with a Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Prudence Heward was published recently by the Visual Arts Centre & McClure Gallery, Montreal.