Head On: Flashpoints and Clashpoints in the Art of Adad Hannah

A man and a woman sit on a bench before a scrubby patch of grass. She is wearing a short dress buttoned to the throat, the fabric a high-sheen blue. Her hair colour, box fresh, matches the blonde wood of the settee. Beside her, outfitted in a suit of black-and-white plaid, is her boyfriend. His short, side-parted hair is combed flat against his scalp. The woman sits forward, straight-backed; the man reclines stiffly. She stares into the lens; his gaze cuts hard to the right. In his lap, one clenched hand is clamped over the other, as if to keep it from swinging. The couple’s only point of bodily contact is displayed dead centre in the frame: her hand on his thigh. The image, from Adad Hannah’s “The Russians” series, is awkwardness incarnate. Tense, uncomfortable, and blatantly comedic, it could have been snapped at a family party: a recalcitrant young relative and his bold new lady. Confronted by the camera, the couple was forced to navigate how to pose, how to present, how to look—the resultant stress is palpable. That the picture is not, in fact, a photograph is revealed only gradually: the woman’s hair blows slightly in the breeze; her boyfriend’s eyes shift nervously. With mounting horror we realize that “Young Couple at a Playground” does not show an instant of photographic unease but several punishing minutes of it—video recorded in real time.

“Young Couple at a Playground”, 2011, HD Video

Adad Hannah is just 40 years old, but he seems younger and has the energy and open face of a happy adolescent. He bounces as he walks, head crowned with ringlets, his stride quick despite the icy January sidewalks of Montreal. He is a confident man. This is perhaps, unsurprising given his quick success: within scant years of graduation from Concordia University, he has exhibited work at major museums in Bucharest, Shanghai, Santiago, and Sydney, has works in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and many others around the world, and has completed projects in cooperation with the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Rodin Gallery in Seoul. His first post-MFA show was attended by the legendary architect and cultural activist Phyllis Lambert and the Oscar-nominated filmmaker Denys Arcand. Hannah has since collaborated with Arcand on two projects and befriended the 85-year-old Lambert. When we met, he was wearing her red leather mittens.

The first time I spoke with Hannah was over the phone from Vancouver, where he is now based. It was Christmas morning—the perfect time for two Jews to find a quiet moment to talk. “I started making art quite early,” he said, shifting one of his two young daughters from his lap to take my phone call upstairs. “My family was supportive. I feel a bit guilty when I hear of artists who had to break with their families and run away from the suburbs to pursue their creative urges. I don’t have a similar story.” His parents were theatrical performers engaged in a practice Hannah defined, after a long moment of thought, as “experimental European performance art.” They moved frequently for work; before Hannah was a teenager, he’d lived in New York City, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and London. The family finally settled in Vancouver in the early 1980s. In high school he enjoyed painting and was encouraged by an art teacher; of his own work, all that decorates his house are those watercolours he made with her encouragement, 20 years ago. He does not like to keep his recent work around.

Production still from “The Diversions: School”, 2011

At 18 Hannah began studying at Emily Carr, where he focused on printmaking and painting before turning to performance art, in which he’d dabbled as a child, working alongside his parents. As part of the five-man troupe “The Human Faux Pas Performance Art Collective,” Hannah toured Canada and the US, performing audience-participatory sequences often from inside a 1,000 cubic-foot inflatable cube. “We did a lot of stuff with inflatables,” Hannah said. “We’d give out packages filled with things like stickers, bits of photocopied drawings I’d done, pieces of 16-mm film. We did one thing where we’d write a description of someone in the audience on a package—black shirt, white pants, glasses—and emerge from the cube and give it to them.” During this time, Hannah began making real-time recordings of the performances and incorporating them into the troupe’s act. “At some point I realized that this aspect—these videos—was more interesting to me than performance itself.” Hannah followed this interest as an MFA student at Concordia. He started by experimenting, testing tools of editing and early tricks of photography—double exposures, half-silvered mirrors and other techniques of conjuring ghosts in 19th-century drawing rooms. Then, rather than padding his work to produce visually unsettling effects, he began stripping it down. “I thought, what if I take things away instead? What if I make a video with no action, no sound? I was left with tableau vivant.” This is what Hannah has been exploring ever since, producing a compelling body of work that comments most powerfully not on performance or video art, but the medium at once most trusted and suspect: photography.

The ontology of photography remains difficult to grasp. For early critics photography was a self-operating process for its complete objectivity, unlike previous forms of representation. Man did not enter into it, save as the lens-cap-removing agent of Nature. Indeed, the daguerreotype was accorded almost supernatural properties for its ability to reflect reality; Edgar Allen Poe reasoned that its power was to be expected, as “the source of vision itself has been, in this instance, the designer.” Once the initial shock of the “mirror with a memory,” as Oliver Wendell Holmes put it, wore off, the idea that photographers were in some measure responsible for the images produced in their cameras began to gain traction. Now, in our post-Barthes, post-Sontag, postmodernist era, the notion of a purely documentary photograph is laughable. Yet the concept of photographic truth persists; it is difficult to disavow that a photograph is, in some way, a slice of the material. Or, to use Hollis Frampton’s memorable butchery metaphor, a cut of flesh from worldly bone. Unexpectedly, Hannah’s tableaux vivants tread the line between document and fiction in a way that the staged photographs of Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson don’t; by expressing photography’s project in cinematic terms, his videos make explicit the performative and constructed aspects of the medium itself, rather than that of a specific picture. As they endure, reality sets in. “Everybody has this thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way,” said Diane Arbus. Hannah’s work, too, relies on, and dramatizes, people’s self-perceptions. As the seconds tick by, the essence of his work becomes apparent, written on the models’ concentrated but shifting faces. (In some of Hannah’s earlier tableaux vivants, they hold poses for up to 10 minutes; the artist later realized he could ask them to pose multiple times if he shortened that to under three.) Time which, with light, is the material of photography—is captured here in a way that a photograph does not and cannot capture it, forcing an experience we do not normally have. With Hannah’s work, unlike in a movie theatre, or in the contemplation of a photograph or in our everyday lives, we are not permitted or encouraged to lose track of time. Instead, we face it head on: this is what it looks like; this is what we look like. For all this honesty, we are looking at a fiction, a movie with actors, a director and an idea behind it.

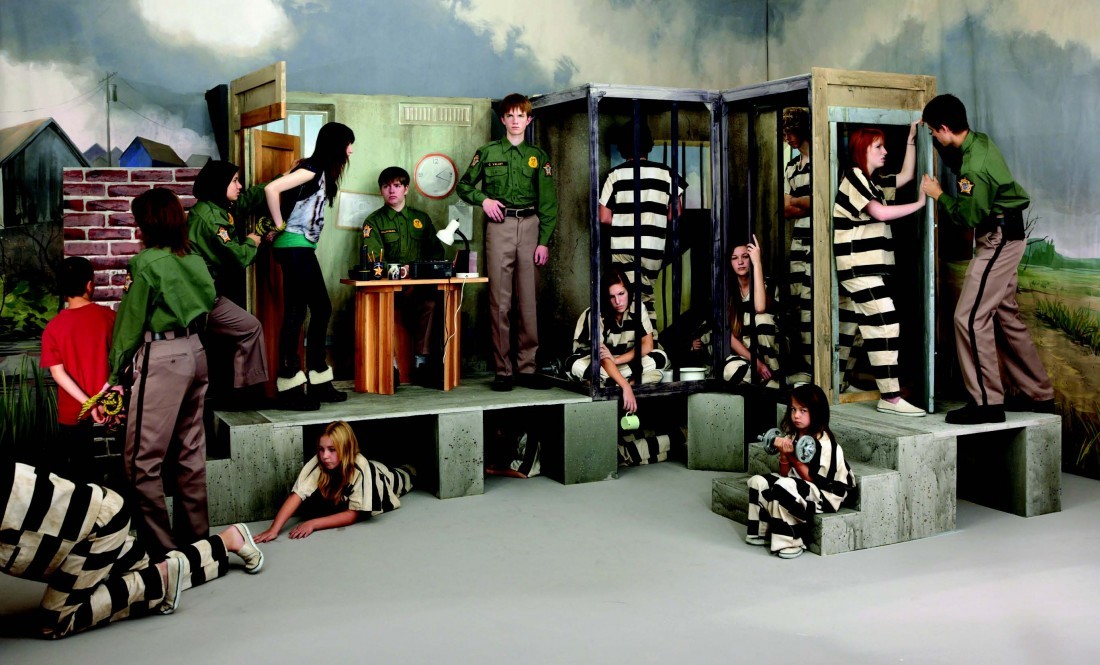

Production still from “The Diversions: Jail”, 2011

Since graduate school Hannah’s work has changed form very little. “I can look at stills I did in 2001 or 2002 and think, I’ve taken two baby steps in the last decade, and get depressed,” Hannah said. “I’ve been digging in similar places for 10 years now. But I still think there’s interesting things to be done there.” Each new body of work (because of production scheduling, he is often engaged with several at a time) typically consists of photo and video components: the (authentically) still images made during filming, the films themselves and live recordings of tableau vivant performances. One shoot can produce numerous videos and photographs, each representing a different perspective on, or alternate staging of, the same scene. The 2007 series “Traces,” commissioned by the City of Toronto for its Nuit Blanche and shot in a local jazz-bar-cum-retro-diner, is comprised of four photographs and four videos. In one eight-minute tableau two women gesticulate, or perhaps reach for bites of each other’s meals, over a table laid with stage-prop food; a photograph shows a woman climbing over her own dinner into her lover’s waiting arms, her knee grazing a napkin. They were displayed for the night of the festival in the bar where they were made, the eight works hovering over the sites of their creation, which had been left exactly as they were during shooting. All that was missing was the models, who now appeared only as images in the worlds they had inhabited. The presentation of All is Vanity (Mirrorless Version), the 2008 project commissioned by the Bank of Montreal for their Project Room in Toronto and later purchased by the National Gallery, played on the same trope: the tableau vivant, a recreation of 19th century American artist C Allan Gilbert’s popular, didactic 1902 illustration All is Vanity, shared the space of exhibition with the set built for its staging. Again, the only elements absent from the mise-en-scène were the models—in this case, twins, posed to appear as a vain woman and her lovely reflection.

As a reinterpretation of a historical artwork, All is Vanity (Mirrorless Version) anticipated what would become another recurring theme in Hannah’s oeuvre. A year after its production he made “The Raft of the Medusa (100 Mile House),” a fantastically ambitious project that involved over 40 members of the small British Columbia community where it was shot in a restaging of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, literally a towering example of French Romantic painting. (The tableau finally consisted of 20 students from the local high school, who had been trained in yoga for weeks prior to the performance so that they would be able to hold their poses, the varied supine, pleading, gasping, reaching, desperate postures that populate Géricault’s tragedy-at-sea scape.) In A Vulgar Picture, 2010, staged for an episode of Radio Canada’s Mange ta ville, the show’s host and staff and various Quebec artists perform “roles” familiar from “A Rake’s Progress,” a 1733 series of eight illustrative paintings by William Hogarth. Hannah compounded the works into a single tableau. The picture is rich and exciting, a sumptuous, complex arrangement of figures and props that teases the eye and entices it to prod. We are drawn in, in short, by the promise of a Baroque drama. The promise isn’t kept.

“I’m interested in having people think about their agency as viewers, as historical agents in relation to an artwork or any art or cultural text,” Hannah said. “Our experiences are valid tools to be brought to the work of art in the present moment. That’s not to say it’s not interesting to learn what went into making a historical work, but when we go into a museum and there’s a panel on the wall that tells you what the piece is about, that suggests that you need to stop there and not create your own meaning in relation to the work. Meaning is arrived at through negotiation.” Hannah’s history works, too, are a negotiation: between imitation and evocation, precision and inexactness. He is not after replication, just as he doesn’t demand complete stoniness from his performers. A good thing, too, as it is in their ineffable humanness, their denial of being photographs, that the heart of the work is located.

“The Raft of the Medusa (100 Mile House) Video 7”, 2009, colour photograph

In Montreal, in his bright but sparse Parc Avenue studio, Hannah showed me clips from a new work, “The Diversions.” Shot at the Gallery Lambton in Sarnia, Ontario, the project involved the construction of two separate scenes—a prison and a classroom, both populated by children. In the unfinished videos I can hear Hannah’s exasperated voice rebuking the players, including one wedged into a corner and costumed in a pointed hat, for their inability to sit still. Another child, sitting cross-legged on the floor, draws his finger haphazardly around his shoes. “The Diversions” will inaugurate the newly renovated gallery upon its reopening this fall. The videos—Hannah’s barked instructions edited out—will be shown before the sets, now empty, on which they were filmed. Jailhouse and schoolhouse will each be in view across a divide. It seems the realization of Hannah’s working ethos: to put ideas in dialogue, to send up expectations and to propose that where there’s one story, another is close behind.❚

Katie Addleman is a Toronto-based writer.

This article won the Gold Medal at the Western Magazine Awards on June 21, 2013.