Hangama Amiri

As of October 2024, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated there were 6.1 million Afghan refugees, making them the fourth largest refugee group in the world. They have at times been the largest, starting with the Soviet invasion in 1979 and in the tumultuous years since. This long-standing experience of exile has led to what anthropologists identify as perpetual displacement, as refugees move from country to country; the effects of migration are multi-generational, and any sense of home and family becomes complex and highly mediated.

Hangama Amiri, installation view, “PARTING/ فراق,” Esker Foundation, Calgary, 2025. Photo: Blaine Campbell. Courtesy Esker Foundation, Calgary.

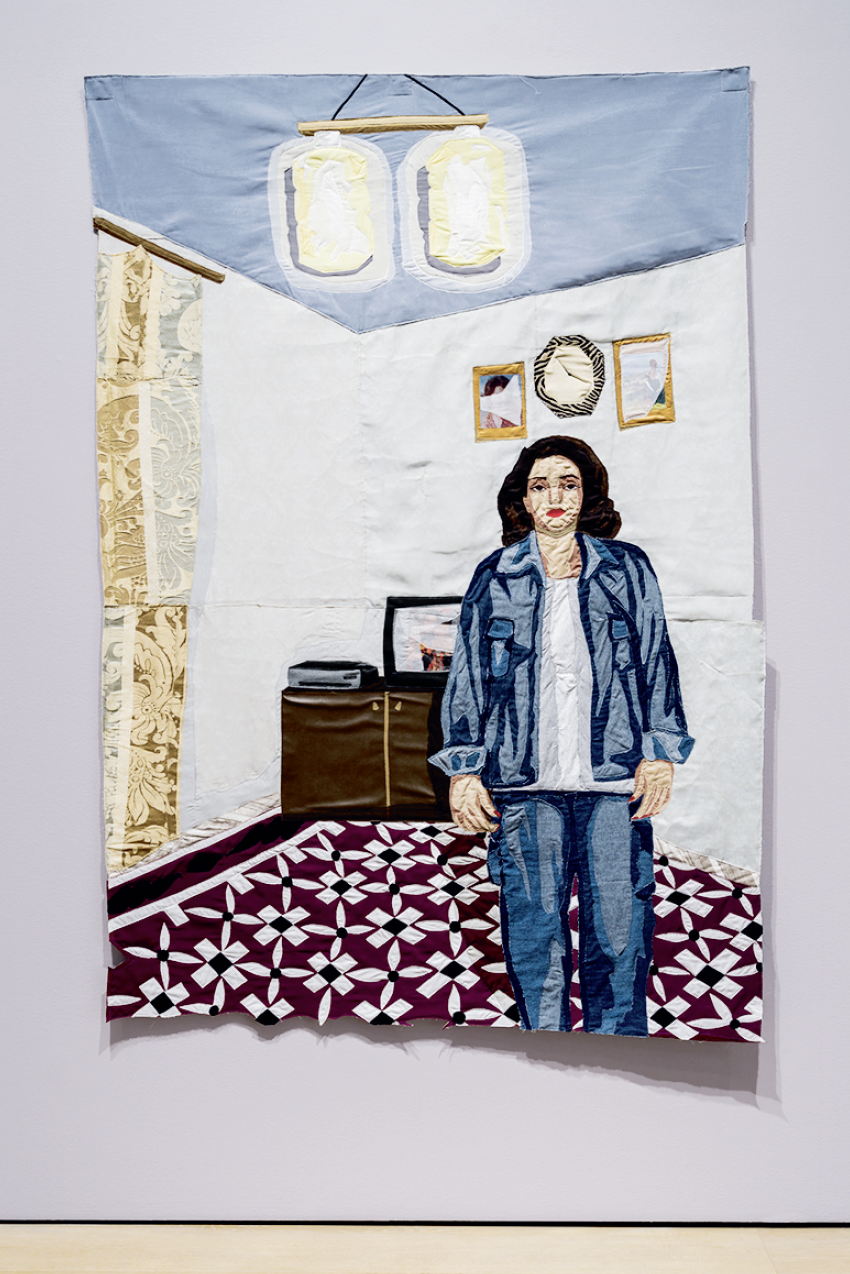

Hangama Amiri’s exhibition “PARTING/فراق,” a series of large-scale textile compositions, comes out of that fraught history, building from the experience of her parents after they fled Afghanistan in 1996. They temporarily settled in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, where Amiri’s mother remained with their four children, while her father moved on to Denmark and then to Norway, working for a tulip producer and in the forest industry. They were apart for nine years before emigrating to Canada. To maintain familial bonds and a sense of home, her parents exchanged letters, photographs and gifts. In Portrait of a Woman with Denim, 2023, for example, the mother wears fashionable Western clothing that has been sent from Scandinavia. The photograph on which the collage is based is an acknowledgement of the gift, which is, in a sense, offered back to him via the picture, sent to him in Denmark. The circulation of affect depends on the circulation of objects, supported by the postal system.

The majority of the works in the exhibition are directly based on family photographs, with the mother typically pictured in interior spaces in Tajikistan and the father posed in exterior spaces in Scandinavia. Although the original photographs are not included in the exhibition (vitrines hold pencil sketches and colour drawings, with notes on fabrics), they are clearly signalled in the naïve compositions and the formal, slightly stiff poses that typically characterize the genre. In Woman Before a Mirror, 2022, the mother looks directly outward, as if trying to establish emotional contact through the lens; the forced smile seeks to reassure the eventual receiver of the photograph; the stiffness speaks to the performance and to the emotional burden these photographs carry. The difference between this photograph-based work and Man with Vase of Tulips, 2022, an imagined portrait of her father in Denmark, is striking. In the latter carefully composed image, a man tenderly embraces a vase as if it were a person, looking down. With no camera present, he fully inhabits his melancholy and longing.

Hangama Amiri, Portrait of a Woman with Denim, 2023, muslin, cotton, chiffon, polyester, suede, wallpaper, faux leather, vinyl paper, clear vinyl, Kodak photo, postcard, silk chiffon and velvet, 190.5 × 179.07 centimetres. Photo: Blaine Campbell. Courtesy Esker Foundation, Calgary.

Amiri works by creating patterns from her drawings and then stitching together pieces of fabric on a muslin background, the appliqué resulting in something that resembles paint-by-numbers. The works employ various techniques to create three-dimensional spaces. Using shading and shadows for volume and depth, they are surprisingly successful at rendering the effects of light. Amiri does not seem as interested in the surface of the work as does a textile artist such as Pacita Abad, who embellishes her work with different styles of embroidery, buttons, mirrors, painting, quilting, rickrack and so on. The stitching here is mostly by machine, and the edges of the fabric are unfinished and slightly frayed. Some of the portraits do incorporate elements other than fabric. In the piece Portrait of a Woman with Denim, Amiri sews a postcard of an Afghan pop star and a picture of a model from an Afghan magazine on the fabric wall of a room and then partially covers them with chiffon to suggest the glare on the glass surface of a frame. In a touristic shot of her father, Portrait of a Man in Ålesund, Norway, 2024, the cityscape behind is a screen-printed photograph that has been overpainted in some places and in others covered with the sheer fabric to make it recede.

What is gained by turning these photographs into fabric works? The loss of crisp detail, along with the irregular edges and the patchwork quality, give the compositions something of an amateur or childlike quality, which is suitable, given the child’s limited understanding of the parents’ lives. The softness and warmth of fabric are also suggestive of comfort and home. But the way that fabric draws attention to the (literal) materiality of these representations also speaks to both the constructedness and the contingency of memory: those memories that survive are often those that are attached to something, such as an object or a photograph or a piece of clothing. Memories, like objects or indeed families, are easily lost.

Hangama Amiri, Portrait of a Man in Ålesund, Norway, 2024, muslin, cotton, polyester, chiffon, denim, suede, silk, inkjet print on silk chiffon and found fabrics, 109.22 × 152.4 centimetres. Photo: Blaine Campbell. Courtesy Esker Foundation, Calgary.

In the context of the refugee’s perpetual displacement, the family photograph plays a different role from how it might in other situations. These photos do not, for the most part, memorialize shared events in a family’s history: no one in the family was there to witness the scene in Man Resting in the Park, 2022, the photograph having probably been taken by a friend or even a passerby. The photograph circulates as both evidence and utterance (I am well, I am happy, do not worry) as well as totem, to be preserved and pored over in an album. Some works gesture towards the status of the photograph as object by attaching external elements: three of the portraits of the father have sewn-in, screen-printed postage stamps in the corner, testifying to the distance between sitter and viewer and the means by which the photograph made its way to the receiver. The arrival of the photograph at its destination (It’s from Denmark! It’s from your father!) would itself have been the event, a promise of the continuity of home. In a related gesture, other works have swatches of rose-printed fabric attached to their sides, suggesting the cover of the photo album in which they were mounted. The photograph has overtaken the memory, or perhaps always was the memory, since the event itself was for the most part never witnessed. These material works speak eloquently to the supports and texture of memory, and to the ways that memories, families and home are careful fabrications, painstakingly stitched together. ❚

“Hangama Amiri: PARTING/فراق” was exhibited at Esker Foundation, Calgary, from January 25, 2025, to April 27, 2025.

Jim Ellis is a professor of English and director of the Calgary Institute for the Humanities at the University of Calgary.