Guillermo Kuitca

Van Gogh on the central problem of representation: “What is drawing? How does one do it? It’s the action of forcing one’s way through an invisible iron wall which seems to be located somewhere between what one feels and what one can do.”

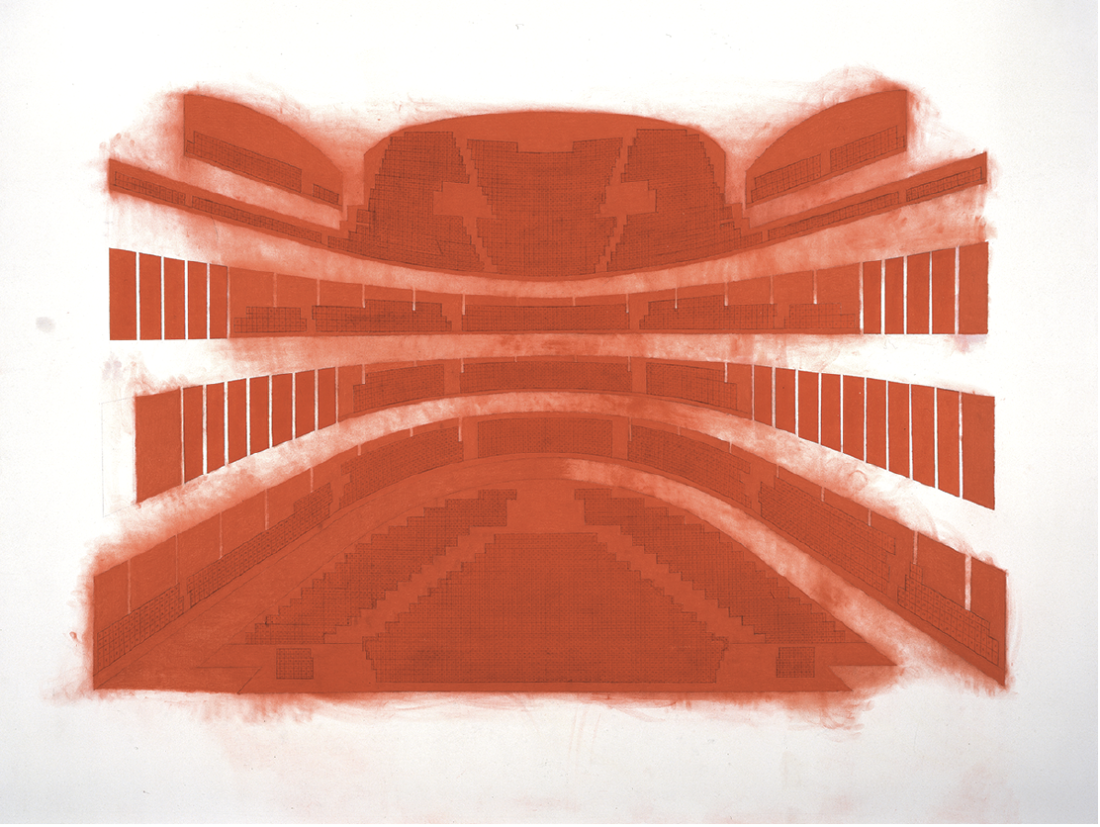

This quotation came to mind recently at the Kuitca exhibit. He’s an artist who has always had a strong sense of the limitations and difficulties of making paintings and drawings. Thirty years ago, vacillating between painting and the theatre, he wrote: “nothing was possible in painting while everything was possible in theatre”—this after what must have been a memorable brush with Pina Bausch’s touring dance theatre in 1980’s Buenos Aires. The paintings he made over the next 10 years, richly represented at the Albright-Knox in Buffalo, adhered to his axiom that “anything can happen in a painting as long as it contains a stage-space.” So, we see through the “fourth wall.” There are wing flats, door flats—some complex scene setting is taking place. Also an emptiness, no actors, just beds, chairs, perhaps a microphone, the props proportionately small on the vast stages. From 1986, there is the series Siete últimas canciones, Kuitca’s response to Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs. The paintings are not specific in their theatrical reference but, rather, as Kuitca said of the Songs, “convey a story without one being necessarily aware of any history or narrative.”

Guillermo Kuitca, Mozart-Da Ponte I, 1995, oil, pastel, and graphite on canvas, 71 x 92”. Photograph: Lee Stalsworth. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, 1995. Courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

His initial resolution for the “problem” of painting, then, uses an artificial space spread out across the canvas. The colour, the light, the lack of actors all contribute to a feeling of gravity—of the drama playing out, perhaps, in the context of a brutal military regime only very recently departed from the scene in Argentina. If Kuitca’s central concern is the representation of public and private space, it must have been an emotionally and conceptually complex theme to develop at this time. From 1976 until 1983, the violation of private space, and the disappearance of individuals from within it, was part of the experience of many in Argentina. The theatricality of the paintings serves as a way of representing this situation, but also conditions his response and ours as viewers to it; the space exists primarily within the representation of a proscenium.

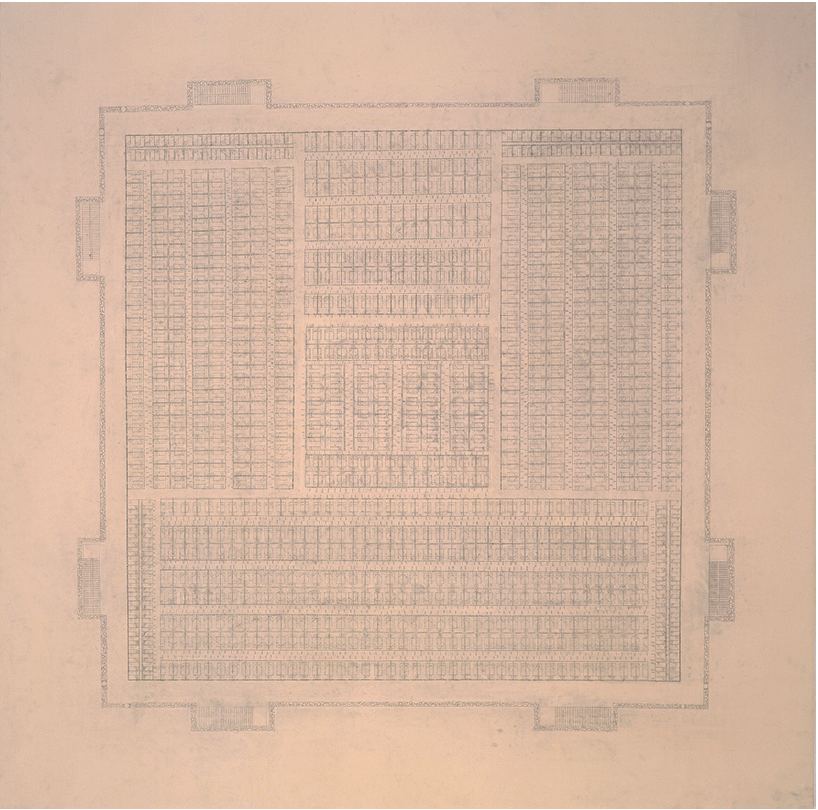

In Untitled, 1991, we see him begin to consider other strategies. There’s still a stage space across the lower six inches of the canvas, a little bed and chair, but the work is dominated by a simple floor plan of a two-bedroom apartment crudely painted in the centre of the work. It is a diagrammatic representation of a private space. From this point on, the exhibition picks up the full range of Kuitca’s consideration of plans and structures and gives us four of the 10 paintings that make up the The Tablada Suite, where the heavily painted apartment plan is replaced by complex renderings of a diagrammatic structure in graphite over painted grounds. These plans are of institutional structures, and it’s not immediately apparent which is which—the prison like a hospital or library, for example. If a theatrical space had offered a way to make paintings, so do the institutional plans and maps. In an interview Kuitca has said that he makes no distinction between architectural plans and cartography because “what interests me is the correspondence between the world and its representation.” The show gives us both, jail plans in one room and maps of Poland on beds in the next. Those maps, on their stumpy little divans, seem in many ways the clearest statement of Kuitca’s purpose, the juxtaposition of the private (bed, the place of birth, sex and death) against the impersonality of public space (we see the route from Wiesbaden to Poznań).

If the Untitled beds from 1992 are a more overt statement, the Tabladas are chillingly repressed. Here, there is none of the friction of dragging a thick, red painted highway line across a mattress. These have the point of a pencil scratching across the surface, cell by tiny cell. The process of making the work, elaborately incremental, reinforces our experience of the individual in relation to the “structured many.” And it is the single painting, often roughly body-sized, that presents this to us, pointing out the impossibility of reconciling the representation of a space with the lived experience of that space.

Guillermo Kuitca, The Tablada Suite VI, 1992, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 78 3/4 x 78 3/4”. Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery Edmund Hayes Fund, 1994. Courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

The surprise of the show, for me, is the last room. There’s an Untitled painting from 1998, an anonymous architectural floor plan with some of the cells loosely filled in. Because of their scale and characteristics, other paint marks on the work appear to be made by Kuitca walking across the front of the painting pulling a brush over its surface. This instance of painting as evidence of action is not unknown in his work. It’s there in “theatrical” paintings 20 years earlier, but here there is a self-consciousness, an awareness of the importance of that act to the painting, which is new. In the same room we see paintings from the “Desenlaces” series, 2007 and 2008, which pick up on this. The gallery notes, “The composition comes from the physical mechanism that Kuitca imposed on himself as a creative procedure: to mark the canvas as he walked beside it.” In these paintings the marks take on two forms, one a slash (they look like a direct quotation of Lucio Fontana), the other a diagonal mark that accrues as he moves around and results in a painting that has a relationship to what the artist terms “topographical cubism.”

For an artist who has customarily broken Van Gogh’s iron wall by using images and structures from outside the studio, this is a radical move. It invokes the physical presence of the artist moving, perhaps juxtaposing that process as recognition of personal space with the public terrain of art history, bringing references to Cubism and Arte Povera. Kuitca has spoken of the work in relation to the “late embrace” of cubism by Latin American artists and, particularly, to the paintings of Alfredo Hlito.

Kuitca has worked for the majority of his career in Buenos Aires. Like William Kentridge in Johannesburg, the hemispheric separation has provided a critical distance from the North America-Europe art axis. This show reveals that Kuitca, with this relative isolation, has developed an alternative means of reflecting on the world, a way of building paintings that acknowledges a range of contradictions that did not seem possible within the limits of the discipline. He has found a methodology to create what Olga Viso has called “resistant painting…. painting outside of painting.” ❚

“Guillermo Kuitca: Everything, Paintings and Works on paper, 1980–2008” was exhibited at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo from February 19 to May 30, 2010, and will travel to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from June 26 to September 19, 2010, and to the Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, dc, from October 21, 2010, to January 9, 2011.

Martin Pearce makes paintings and drawings. He teaches in the School of Fine Art and Music at the University of Guelph.