“Greystone: Tools for Understanding the City”

When I was well before the age of 10, walking through Old Montreal in the intrepid company of my great-aunt, we would often stop with admiration in front of those impressive redoubts, those massive monuments of pale grey stone. I was so struck by the gravitas that seemed to emanate from them that I once asked her (and she reminded my parents of this for dog’s years after): “Is this where the gods live?”

I was greatly taken with those éminence pierre grise edifices, their carapaces of millennia-old grey limestone standing so strong, unassailable and tall on the streets of the old city of Montreal. Later on, I recognized that the emotional charge I felt when I saw the building (albeit of white marble) at 23 Wall Street immortalized in Paul Strand’s 1915 iconic photograph—of Wall Street workers passing in front of the monolithic Morgan Trust Company—was somehow rooted in and irremediably wed to this early memory.

This bluish-grey rock is generally referred to as “Montreal Greystone” and lends Montreal architecture its distinctive tone and tenor. Greystone was once found in abundant quantities in the quarries that pockmarked the island of Montreal from stem to stern. It was also widely used in manufacturing the lime needed for masonry work. Around 1850 over 2,000 residents of the village of Coteau-Saint-Louis worked from sunrise to sunset, quarrying stone.

The splendid survey of Montreal’s greystone buildings at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) that spurred recovery of the above memory had its inception in a highstakes scavenger hunt through the city streets that would later entail an expansive and multi-tiered (metaphorical) archaeological dig of the pertinent local material history from the late 17th to the early 20th centuries. Like excavating alluvial deposits to determine growth strata, an in-depth study of the greystone buildings does not just begin with pierre grise, but demonstrates how different layered strata of topography, politics, ethnicity, culture and technology have in concert materially shaped Montreal through the centuries.

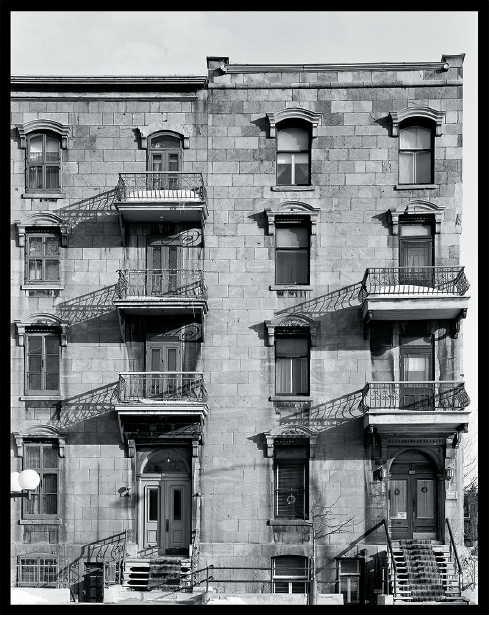

Installation view, “Greystone: Tools for Understanding the City,” 2017, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal. Images courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Thanks to what was conceived at the outset as a photographic mission by Montreal’s reigning deity of architecture and heritage, Phyllis Lambert, to visually document greystone buildings, we are now able to reap a bountiful harvest of photographic images and related research tools that preserve and lay bare the history of Montreal’s built environment. The mission was enacted by Lambert with Richard Pare through sundry walks in Montreal neighbourhoods in the early 1970s. Pare, who had only recently graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago when he signed on for the expedition, went on to become the curator of Seagram’s photography collection from 1974 to 1984 and subsequently became the founding curator of the photography collection at the CCA.

Lambert recalls that she and Pare conducted their mission in the winter months, courageously trekking through the snow from early in the morning throughout the daylight hours, identifying greystone edifices from Old Montreal north to the faubourgs—St-Laurent, St-Louis and St-Jacques—and beyond to outlying suburban towns. It may be hard to believe now, but they had only one map from 1890 at their disposal, as relevant archives were simply not accessible like they are today in the era of the Internet.

The exhibition, installed in the CCA’s Octagonal Gallery, is a model of didactic excellence and is enhanced by info-laden maps. Photographic images are, of course, the cornerstone of the exhibition. They are exhibited alongside the maps to help viewers understand the infrastructure and topography of the city, a timeline of its buildings’ construction dates and the many players involved. The research team collated primary documents that include insurance atlases, historical city maps, cadastral plans, municipal tax assessment rolls, city directories, notarial records and a wealth of private papers—everything needed to build up an impressive and expansive social history. The result is a luminous triumph of legwork, passion, technical virtuosity, scholarship— and dogged perseverance.

If Lambert’s original mission was predicated on the visual image, it organically morphed into a pioneering campaign to preserve the city’s heritage—one that continues uninterrupted some five decades later. It is a campaign owing largely to her unbridled passion and consummately stubborn, contrarian nature. Her abiding attachment to those buildings was perhaps encouraged by the fact that early on she lived for a number of years in Chicago, studying at the Illinois Institute of Technology, and beginning her activist-oriented career in architecture. Interestingly, “Greystone” is a style of residential building endemic to Chicago (most often built with Bedford limestone quarried from southcentral Indiana). Beginning in the 1890s and continuing through the 1930s, greystones were being built at a hectic pace and an estimated 30,000 still remain standing. On her trips back to her home city, Lambert’s eye began to hone in on our own native greystone facades, and that eye, tireless and penetrating, sought them out wherever they could be found.

Phyllis Lambert and Richard Pere, Lusignan/ Guy-Fabre Row Houses, Saint Jacques, 1866. Photograph taken between 1973 and 1974. Phyllis Lambert Collection. © Phyllis Lambert and Richard Pere.

Ingrid Birker, a paleontologist who works at McGill University’s Redpath Museum, has said: “One inch of greystone represents about 10,000 years of sedimentation.” Most greystone buildings in Montreal contain shells and coral-like animals locked into their epidermal layers. When you start seeking them out, they begin to pop out from the stonework everywhere, whether at Westmount City Hall, Selwyn House or the former post office on Sherbrooke Street West.

To Lambert’s inordinately well-seasoned eagle eye, the way that the greystone was cut and laid, as well as a building’s strategic location, speaks volumes, not only about the incremental growth of the city in time, but the identifying ethos of builders and owners, entrepreneurs and occupants. Throughout the course of the 19th century, the stone was taking on a markedly symbolic value, becoming an indicator of affluence, authority and even cultural identity.

We may appreciate the greystone buildings as aesthetically beautiful, iconic and worthy of preservation today, but when Lambert began her investigation, they were taken for granted and in constant danger of demolition. It is no exaggeration, I think, to state that Lambert is the incarnate conscience of our built city. “Greystone: Tools for Understanding the City” is only the latest in a long line of projects that bears the hallmark of her devotion and diligence in the context of research and museology. She founded Héritage Montréal in 1975 and, a scant four years later, the CCA. She saved the historic Shaughnessy House from demolition and restored it, integrating it into the CCA’s international research centre and museum, which opened in 1989. In the mid-1970s the inaugural study of greystone buildings was conducted by the Montreal Greystone Building Research Group under her aegis. Since its inception the CCA has played an invaluable role in promoting public understanding and debate on the role of architecture in society. It has nurtured scholarly endeavours and mounted innumerable exhibitions on architects and architecture from around the world. Our understanding of Montreal as an historic city inside North America has been immeasurably enhanced by Phyllis Lambert’s brilliantly incisive, stalwart and unflagging efforts to lay bare the fundaments of Montreal’s built world and to preserve them so that they might flourish in the fullness of time. ❚

“Greystone: Tools for Understanding the City” was exhibited at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, from October 13, 2017, to March 4, 2018.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal, and is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.