Gordon Lebredt

“Where does a show begin? If we are to approach an exhibition must it not have an edge or border?…Does the show begin with the ‘arrival’ of the announcement, a silent ‘come on’? Or does it begin with the walls of a museum or gallery, at the threshold of the display space itself?” asks Gordon Lebredt in his 1981 artist statement, What Exhibition? Where?

His posthumous exhibition, “Not To Be Reproduced,” organized by Joel Herman at G Gallery in Toronto, includes sculpture, video, text-based wall work, photographs, posters and magazine clippings. It is difficult to discern works from non-works, the essential from the supplementary. In fact, Lebredt’s production over the span of his career frequently challenged this distinction—even his eloquently and neatly drafted unrealized exhibition proposals evoke finished works.

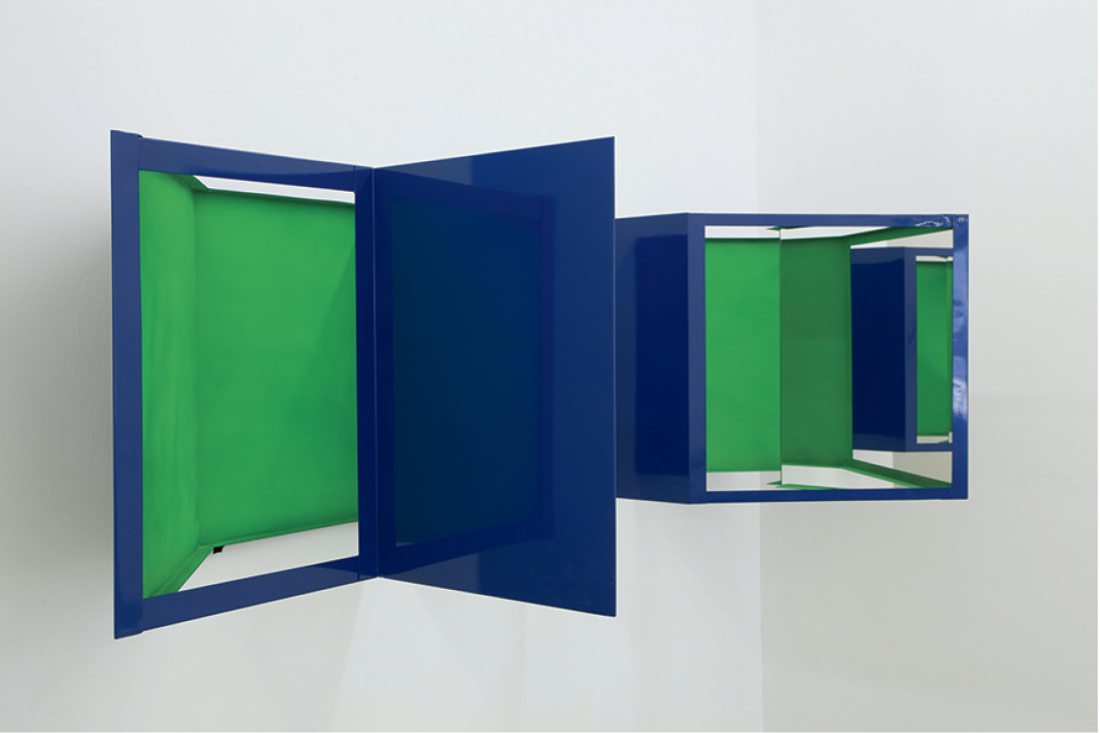

Gordon Lebredt, Facsimile Enantiomorphic Chambers, 1982/2010, painted metal, mirrored glass, 24 x 34 x 24 inches. All photographs: Ryan Park. All images courtesy G Gallery, Toronto.

Lebredt regularly made reference to other artists, writers and theorists, and his pieces often feel like the outside of something already said (perhaps the root of his interest in ventriloquism). This is especially true of Facsimile Enantiomorphic Chambers, 1982/2010, a replica of a Robert Smithson piece, Enantiomorphic Chambers, 1965. Composed of two sculptural parts fastened to the wall, its structure was derived from the Wheatstone stereoscope, a device designed to converge two almost identical images into an optical illusion of a three-dimensional whole. As in Smithson’s original, Lebredt’s mirrors reflect inward, reflecting themselves reflecting. Rather than converging together, each metal chamber creates a curved path of infinite reflections. According to Lebredt, Smithson’s sculpture was exhibited only once and documented in two photographs before it went missing. As a result, later descriptions often misconstrued the functioning of the mirrors (some writers attributed a much richer visual experience than arguably could be produced, others were disappointed after mistaking a maquette for the original). In his writing, Lebredt analyzes the various design possibilities, technical problems and misinterpretations of how the piece functioned. For Smithson, it seems the essential optical function of the piece was to make viewers disappear, erasing them in the interior reflections. Perhaps for Lebredt the work’s history has a more compelling function—snared by the surrounding contradictions and misunderstandings, the piece itself exists in a constant state of erasure.

Erasure of the self was a frequent topic for Lebredt, and many of the texts in this exhibition read like existential meditations: “…I am no longer either my presence or my reality, but an objective, impersonal presence…” (Trade-marks, 1982) or moments of crisis: “YES, IT IS REALLY ME.” (Sometimes this scene…, 1982). The latter comprises two adjacent picture frames housing short texts, one accompanied by a blurry black and white, anthropomorphic shape. The text describes the experience of looking at your own mirrored reflection split in two by a harsh light from above: “Indeed, there comes a moment when I encounter that / which is always absent in my image—the glimmer / of a surface that, in eluding me, grasps me and shakes / me at every turn and from every quarter in a dazzling / play of light. I am replaced by a hole…” Lebredt thus finds an absence within his presence, an other’s gaze within himself. This splitting exists in all of his work as he consistently finds a space, a plurality within a whole.

Gordon Lebredt, installation view, “Not To Be Reproduced,” 2014, G Gallery, Toronto. 53912txt.

Occasionally, Lebredt deals directly with an absent presence, as with an unfinished building which lingered, ghostlike, for over 20 years in the Toronto skyline. The video Outers, 1983, a “round-trip” to an abandoned construction site, alternates between passing views of the cityscape and shadows of a revolving model of the unfinished building. He travels, we travel (with him), Smithson-like, moving back and forth between site and model (non-site). In this exhibition, the area around the video is filled with supplementary material: production notes are mounted on the wall, a printed script (of the video’s narration), catalogues and a C Magazine article lie in a nearby vitrine. In one of these texts Lebredt argues that a model has a kind of split existence: simultaneously an architectural space and a representation, “neither a thing-in-itself nor a ‘reality.’” The surrounding texts, too, seem to have a split existence; they elucidate, yet somehow equally fall in and outside the work, separating into written and visual language. Lebredt’s sparse, crisp aesthetic appears like fine penmanship, his work, nonwork and unfinished work are as well crafted as his texts. Your mind wanders across the walls, scanning the text-based wall works and documents. Should you read the words or see them only as marks (like brush marks on a canvas) or both? You may finally ask, where does a text begin? Does it not have an edge?

Lebredt seems to end all his output with a question, an invitation for experimentation, for philosophical investigation, like tugging on a wound-up piece of yarn that always leads further, unfurling another knot. And still it continues, as his works probe deeper even into the most banal, simple experiences, like looking at yourself in the mirror. ❚

“Not To Be Reproduced” was exhibited at G Gallery, Toronto, from May 23 to July 5, 2014.

Wojciech Olenjik is a visual artist and writer, who currently lives and works in Toronto.