Going Deep: The Art of Tala Madani

In the following interview the Los Angeles-based artist Tala Madani admits that she is “deeply not afraid of failing, deeply not afraid of really screwing up.” I believe she is telling the truth, but over the 16 years since she first began exhibiting, there is very little evidence of that failure. Since graduating from Yale in 2006 with her MFA in painting, she has participated in some 45 solo and 114 group shows, and her paintings, drawings and animations are in the collections of museums around the world. It’s the screw-up that’s been a failure.

Which is not to say that things always go smoothly. Madani’s work is overowing with mayhem, disappointment and danger. In the single-channel animation called Wrong House, 2014, a collection of innocent people—a canvasser, a milkman, a pair of salesmen and a guy in a muscle shirt—knock on the door of a man who paces inside his apartment. He greets them with strangulation and tosses each bloodied body into the room until the next person comes along. Their dispatch has about it a kind of dark, cosmic karma; they arrive and as a consequence they are dead. “Beauty is death,” Madani declares in this interview, “beauty is the distraction we don’t need.”

Tala Madani, installation view, “Dirty Windows,” 2023, 303 Gallery, New York. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York. Photo: Justin Craun.

The distraction she provides us with is unique in contemporary art. The sandbox she plays in is full of bodily traces—urine, cum, shit and vomit are everywhere expelled and projected. It is all done in a spirit of carnivalesque humour; along with Bataille there is more than a scoopful of Bakhtin in Madani’s world. As she happily remarks, “there is something about caricature that allows for perversity.” Her paintings are occupied by bearded, big-bellied, balding men, children who are variously playful and murderous, and mothers who take their shape from excrement.

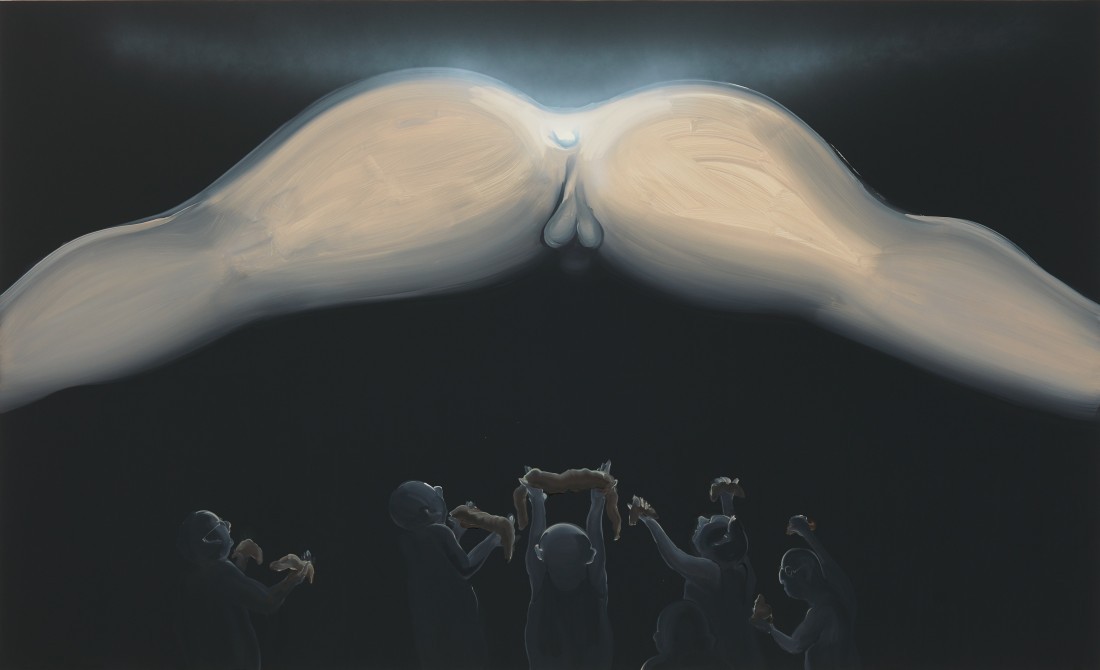

Everything is exaggerated and spotlighted: a phallus towers above a romantic seascape like a flesh obelisk (Sea Dick, 2022); a naked man bends over and the light emanating from his anus mimics the setting sun (Sun God, 2016); a pair of children ride their scat mom in front of a backdrop that could have been painted in Helen Frankenthaler’s style of staining (Shit Mom (Dream Riders), 2019); a tiny, lone child crawls towards a light source and casts a huge, ominous shadow (The Shadow, 2018).

Bad Weather, 2023, oil on linen, 203.2 × 195.6 × 3.2 centimetres. © Tala Madani. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York. Photo: Justin Craun.

Cloud Worship, 2023, oil on canvas, 431.8 × 340.4 × 3.8 centimetres. © Tala Madani. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York. Photo: Justin Craun.

Madani is fearless and is her own best contrarian. “The minute you define something is when you want to break it,” she says and immediately shifts from the impersonal to the personal. “The minute I feel I know something is when I want to scratch the problem again.” She was aware of the problem of female representation in art history and was determined that she would not contribute to that visual history until she could “add something of value.” The Shit Moms, as she named them, are that singular and accomplished addition. These mothers do normal things: they play with their children, they groom and protect and nurture them, all the while existing in their reducible state.

They also do things on their own. In Shit Mom Animation, 2021, she wanders into a large house and moves from room to room, leaving her trace on every surface. It’s like an episode of The Lives of the Rich and Fecal. I am reminded of one of the “Crazy Jane” poems by WB Yeats, who tells us that “Love has pitched his mansion in / The place of excrement.” In Madani’s animated translation of that poetic idea, the Mom is the person of excrement who meanders through a mansion with her own variation of love in mind. Madani understands that materials have their own characteristics: paint is intelligent, electricity flows, shit smears. That malleability becomes especially problematic for the Shit Mom when she decides to engage in a little self-love. On a chaise in the bedroom she masturbates but fails to cum, and in frustration bangs her head against a tabletop until she has no head. Her solution, like a child playing with clay, is to fashion a new one. Her finger-work in self-building is more successful than her attempt at self-pleasuring, and she is able to conclude her house tour.

Let me return to Yeats and his inclination for getting down and dirty. In “The Circus Animals’ Desertion” he precisely places us in the location where artistic inspiration occurs. “I must lie down where all the ladders start,” he writes, “In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.” Madani is down there on the first rung of the ladder, rummaging about the rags and bones, gathering the fair and the foul, and making art out of what is whole and what has been rent. She moves from the bottom rung to the immense, blue, shape-shifting sky. The Shit Mom becomes the Cloud Mommy and in the process Tala Madani leaves some marvel along with the mess in the firmament’s upper reaches.

Tala Madani was interviewed by phone to her studio in Los Angeles on May 22, 2023.

Shit Mom (Dream Riders), 2019, oil on linen, 195.6 × 203.2 × 2.5 centimetres.Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Border Crossings: I know you have a connection to the tradition of American painting and have referenced Morris Louis and Dan Flavin. But you also mention Robert Motherwell, and I’m trying to figure out, other than the residency you did in Provincetown after Yale, what your interest in Motherwell would have been.

Tala Madani: When I was growing up in Oregon, I got a scholarship to study painting at Oregon State, where I was basically at the mercy of the professors in learning about the history of art. At that moment I wasn’t self-motivated and there was only one museum in Portland. So I’d get lost in the library stacks where I’d find books, but those always threw me more towards Roman and Greek histories of art. The interest in Motherwell came from Clint Brown, a wonderful drawing teacher at Oregon State. His excitement about the figure was amazing and his love of art was transferable. I really got into the “Elegies to the Spanish Republic.” I was taken by Motherwell’s forceful line and the pleasure of withholding and the pleasure of giving in his work. The abstraction that was never abstracted. His work is so resonant because I found it at this very innocent moment. When you know too much, you can’t have that pure pleasure.

In some of his paintings Cy Twombly used an excremental palette. I thought he would be someone you might have been interested in. But you don’t go to Twombly.

What I love about Twombly is that his abstractions read almost as linguistic signs—linearly—somewhere between saying something and crossing it out and not saying it. He’s engaged in a discussion about the failure of a painterly language. His work has such emotional resonance whenever you look at it. Then in the very late pieces, with the physical circle, you could also say he was in communication with minimalism. His preoccupation with European mythology probably also meant that my communicating with him would have been twofold down. With Morris Louis, though, his project was so particular and confined to itself that positing stains and figures into his language felt very fruitful. Staining the project of minimalism felt very satisfying. But I’m deeply uninterested in painting nostalgia and in nostalgic painting. I’m not interested in having a conversation with everybody. It’s only when it’s pertinent; only if it feels it could be additive in a discussion.

The other surprising thing is how late you came to an awareness of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy. McCarthy has since become a friend of yours and you’ve had interesting public conversations with him. But given the transgressive nature of your work, they would have been congenial artists for you to look at, especially because they’re also from the West Coast.

That’s absolutely true and there are a few reasons for that. One was the conservative nature of the institutions where I was studying. Even though we were on the West Coast, Oregon State wasn’t steeped in performance or transgressive works, and Yale was interested in building on an East Coast tradition of art history. That was taken ever so seriously and nothing could touch it. And you didn’t see that particular work in the museums I would visit once in a while. There was the Internet, but in the ’90s the Internet wasn’t as full of content. So it was a reflection of the educational institutions I went to, but in my head and in my work I was also trying to figure out something for myself. I went where I went and I saw what I saw. I would reflect on it, but my way of processing wasn’t to look for everything. It was to burrow down; to not check the weather all the time but just to keep digging.

Shitty de Milo, 2019, oil on linen, 43.2 × 53.7 centimetres. Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Nature Nurture, 2019, oil on linen, 40.6 × 35.2 × 2.5 centimetres. Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

You said that you’re interested in “painting beyond your abilities.” What exactly do you mean by that?

This is interesting because I was flipping through your interview with Motherwell and I stopped at the section where he’s basically saying what I’m saying, which is that painting is fresh every time. You don’t know what you’re doing, and what you’re doing might not work. After all these years of working, how can this still happen? I do think there’s intelligence in certain substances. Like electricity knows where to go. Paint is similar for me. It’s a very intelligent material. What gets me excited is starting from something that I have an idea about but don’t know how it will actually come into being. What always brings me back to the studio are the things that didn’t work. It’s also the demand on myself and my work to keep excavating and not settling into repeating what I know.

So is painting always a struggle to find the appropriate language for the subject?

Yes, I think that’s true. It wasn’t a struggle to find my language as a whole. I think the language thing got resolved quite early once I decided that I wasn’t interested in academic painting. I thought that I would lean into my line, or my speed, and the language found itself. But in each instance of a painting, finding the most interesting way into the idea is the play. Again, play, not struggle. What I wasn’t interested in was representing something in a belaboured manner. I don’t want to work too much for the painting, but I want the paint to do a lot for me. So if I had an idea, how could I give that idea an image? If it’s a complicated idea, how can I make it work simply? That’s the thing. I’m interested in a much more direct kind of work and a direct, not stale, way of using my own energy. That’s basically it. Having an idea and trying to make an interesting painting out of it. There are a zillion ways you could do something, so what is the most interesting one for you?

You find painting a visceral thing, don’t you? I get a sense that your engagement is in the moment of making and not necessarily in reflection subsequent to that making.

I think the reflections come rather before than after. But in the making, I’m very present. “Visceral” is a hard one. For me, painting requires both the conceptual and the visceral. Being present is both emotional and intellectual. Painting = sex + chess.

Is that presence because you love the actual material of paint so much?

No, it’s more about the attention the painting requires, or my enjoyment in negotiating a way to forget the day, to forget time and space. You have to get into that mental space of letting things go in your brain and being focused. I have to say, it’s very childlike. I don’t know how to explain it, but when you say “visceral,” it suggests something very active. Sometimes it’s lighter than that.

Curtains #3, 2019, oil on linen, 46 × 61 centimetres. Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

The Shadow, 2018, oil on linen, 203.2 × 203.2 centimetres.

When you address colour in your work, you talk about wanting it to access what you call “a kind of childlike happiness.” I notice how often the subject of children and the notion of innocence come up in your work. Is it ridiculous to ask you whether or not you feel innocent in the work you’re making?

That’s a beautiful and interesting question. I have to put myself in that head space and think, how innocent am I, really? I probably know too much to be truly innocent. Maybe it’s more like Hansel and Gretel and the witch with the candy house. It’s sort of, “Enter, I won’t really eat you.” And maybe the witch was innocent. In one movie, there was a line about Hansel and Gretel being these two naughty kids who were ruining everything by wanting to eat it all. They weren’t victims, and what they were doing was flipping the perspective. I don’t think it’s innocent. It’s a knowing desire to play in that language. Some of that is definitely in response to the macabre and the wilful dehumanization of the bearded man in the Western context. I decided to play with that phobia and make him more desirable or question the fear. Or with Shit Mom, making a new iconic figure of a mother who shows up the masculine perspective on motherhood and women in art history.

You’ve used the word “transgressive” in previous conversations. At one point I think you were surprised that the “Shit Mom” series (2019) didn’t get more of a reaction than it did. Is one of your purposes to be transgressive?

I think transgression is very important, especially when we find ourselves in conservative times. I’m not interested in transgression to the point of repulsion. I’m much more interested in being in the candy house. What really interests me are the ideas. I want the ideas to connect, so the transgression is about transgressing my own sense of things. Sometimes it’s stretching my conservatism, my sense of what’s possible, or my own sense of the nature of female representation. In art history that representation has been problematic, and I wasn’t going to participate until I found a way to add something of value. I think I did that when I found Shit Mom. I fear my transgressions are not at the same frequency as some other artists’; in the last century we’ve had a lot of explosions. I’m actually quite surprised when people think that my work is difficult; I find it quite easy. I wish it was more difficult. Again, I would love to transgress my own sensibilities; that’s much more interesting to me than having someone else react in a certain way. You can’t ever know what people’s reactions are going to be.

You mention the depiction of the woman’s body. There are moments in Shit Mom Animation 1 (2021) when, stepping into the light from outside the window, she cuts a figure that is beautiful. Were she not made of shit, she’d be an object of desire. The same thing happens in Shit Mom (Recess), with the prone mother. Are you playing inside a frame of representation in which that view could be possible?

Shit Mom has a lot of range. As a culture we are very able to sexualize and project desirability onto anything and everything. Even Shit Mom becomes hot. My interest is in her malleability.The painting Shit Mom (Goalpost), where the kids are actually re-forming her body as a goalpost and playing ball with it, shows that malleability.

At My Toilette #3, 2019, oil on linen, 38.1 × 30.5 × 2.5 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

At My Toilette #2, 2018, oil and acrylic on linen, 38.1 × 30.5 × 2.5 centimetres. Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Seen through the lens of Winnicott’s child psychology, Shit Mom is a simple acknowledgement that mothers can fail. So you can be a “shitty” mom but still be a good mother in the process of raising children. One way, then, of thinking about Shit Mom is not to see her as substance but as a woman operating in the complicated world of children and life.

Absolutely. I can take it even further in that children make their parents an image of what they want. Maybe there was no mom, maybe the kids made her out of their own faeces. We haven’t gone through the smashing of parents in a healthy way. In Greek mythology the son kills the father, but in Iran we don’t have that. In our story the father always kills the son. I’m not a historian or an academic, but I’d venture this might be pervasive in Asian cultures. These hero myths are alive and they actually operate on our psychology. They represent that sense of subversion that we talked about before. It starts from the self; I’m a product of that cultural set-up, and I have a definite interest in breaking this hold of all that’s sacred and letting it actually flow.

In the 1978 book History of Shit, the French sociologist Dominique Laporte argues that the history of shit is the history of subjectivity, which she links directly to modernism and the individual. She argues via Freud that we get civilized when we bring ourselves order and cleanliness. Of course, Lacan and Bataille would argue exactly the opposite, that what is important is the unorderliness of shit. I would place you more in the Bataille/Lacanian tradition than in the Freudian one.

I’m not quite sure what category I fall into. Bataille for sure. People were obviously much more comfortable during the Middle Ages with bodily functions because they didn’t have the plumbing that we have. It makes me think of Aleksei German’s film called Hard to Be a God (2013), a film about humans who have travelled to a different planet, and the people living there can’t move beyond the Middle Ages. They’re stuck there and the humans from Earth are trying to help them, but it’s not going very well. The camera seems to be at the belly button or the groin of the cinematographer, so everything is from the belt. You just see people’s hips; their heads are always cut off or in the distance. Even though it’s a black and white film, you can smell the shit. I’m much more interested in facing that. For me, the shit that’s bad is the fascist-control variety, and whatever is loose and uncontrolled is a celebration. That’s the answer and the way to go forward in life. That’s our salvation. That’s where you’re going to stop self-oppression and self-suppression, which is interesting in this moment of people being careful and cancelling themselves. I’m not keen on the level of self-control that’s happening.

Sea Dick, 2022, oil on linen, 43.2 × 50.8 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

I want to talk about beauty and its opposite. In the prologue to The House Is Black, her 1962 film about the lepers of Tabriz, the poet Forugh Farrokhzad uses the word “ugly.” What I find amazing about the film is the transformation that occurs when we come to recognize that the lepers in the colony have a beauty about them. That transformation is one we rarely see.

If it is beautiful, and I’m not sure I would describe it that way, that would be the same conceptual failure as the Shit Mom being beautiful. I know that black and white films can be beautiful, but from my perspective it was a disturbing piece about another revolution. It was about these forgotten people and it was a protest that talked about the failures of the Shah’s regime. But this is the problem for me: beauty is death; beauty is the distraction that we don’t need.

Farrokhzad has a fine poem called “Window,” in which she writes that one window “can summon the sun,” “opening towards the expanse of this repetitive blue kindness.” Your last exhibition at 303 Gallery in New York was called “Dirty Windows” and in paintings like Cloud Mommy and Shit Glyphs, you use a blue and white palette to make a celestial connection through wispy, cloudy figures. I see you making a direct reference to Farrokhzad’s expansive windows.

That wasn’t what I intended, but the connection is not surprising. What makes the poem work so brilliantly is that we all have our windows. As an artist you are very often experiencing the world through limited structures. The painting is always the window, the line through, so there was a possible painting reference. But truthfully, I wasn’t interested in the references. I just wanted the sky.

How do you make decisions about scale?

The scale of my work is really important because it defines what kind of painting I’m going to make. I refer to it as the “ego” of the painting. If the painting is screaming, I contain it in a smaller scale. Sometimes it needs to be looked at intimately, and then if the idea is broader and bigger, it can be a bigger painting. Sometimes it’s about the frequency and pitch of the work; if it’s too high, I won’t make it so large because I don’t want it to scream. I want there to be a humming frequency that traps you. But even as I am assuredly telling you about the scale thing, I want to immediately negate myself and say, “Wouldn’t it be amazing to make a gigantic Shit Mom and see what happens?” The minute you define something is when you want to break it. The minute I feel I know something is when I want to scratch the problem again. If I’ve created a situation, then I go and ruin it and see how I can play the game differently, while still holding on to my ideology.

The Landscape, 2017, oil on linen, 203.2 × 335.3 × 3.2 centimetres. Photo: Flying Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sun God, 2016, oil on linen, 43.2 × 50.8 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

Do the paintings talk to you as you make them, or do you have a very clear sense of what the painting is going to be in the beginning? Then the conversation with the material isn’t as critical as getting through the process of making?

The only time that I planned each painting was when I was pregnant and I didn’t want to erase. Not that I erased that much, but I didn’t want to have any exposure to thinner. Because I was about to give birth and I had a deadline for a show, I sketched the ideas for each painting more thoroughly. Those are the “Smiley has no nose” series (2015). Normally, the sketches are just the first idea and then I figure them out. Sometimes they just lie around in the sketchbook and they may or may not make it. I definitely like the idea of responding to paintings as they’re developing and not just executing them. There’s always that discussion with paint.

I was interested in your reaction to the first Shit Mom painting. You said, “Why haven’t I seen this before?” Which raises the question: Is painting and drawing a quest for originality? What you want is to find something you haven’t seen before? Is that the generative process?

When you put it like that, it’s a huge undertaking. I imagine if I were doing that, I’d be really frustrated. I recognize that would be of value, but I have quite low stakes for myself. I’m deeply not afraid of failing, deeply not afraid of really screwing up. The whole project is more about seeing if you can make magic from that. It should feel fresh. If I see it around, I veer away. If I see it in the vernacular of the moment, I go somewhere else. I also do believe in a group consciousness. Sometimes I get ideas from the ether that are not useful. Ideas will come to you. Maybe you see something; maybe you saw something and now it feels as if it’s yours. That’s why the sketchbook is useful because you can get it out and see if it’s fruitful. It’s your life, so you don’t want to be busy with other people’s interests. You don’t want to fall into the wave; you want to make your wave, one you can swim in. But it’s also much simpler than that. When I was going to school, there was a sense that everything had been made and it wasn’t possible to make anything new. I found that terrible and I never accepted it. And there are cultural implications with this kind of thinking. If we actually think on some level that everything has been made, then we are forgiving of all the stuff that gets constantly regurgitated. This is a capitalistic project more than a creative one, and I don’t do that to myself.

Corner Projection with Prism Refraction and Buckets, 2018, oil on linen, left panel: 182.9 × 182.9 centimetres; right panel: 182.9 × 365.8 centimetres.

I can’t help but think that the provocation for a painting like Babyocracy I (2021) was January 6th. Instead of having insurrectionists invading the Capitol building, you’ve got this naked baby crawling across the desks, causing members of the House to scatter in every direction. Did it come from a real-time political event?

This was very interesting. Years before, I had just had a child and I realized that so many public spaces in America or in the western hemisphere are not attuned for having children. They’re not made for that. Children are expected to behave themselves in public spaces, which is not so much the case in Iran. Kids are everywhere. There are videos of Khomeini giving his speech and there will be a child running around behind him or sitting there listening. I read this story about a woman in Kenya, a parliamentarian, who didn’t want to miss a vote day, so she took her child because she couldn’t find anyone she could leave the child with. People left Parliament that day in protest because she had brought a child. I was listening to stories of this kind where a child disturbs adult behaviour and the reality was that the adults were the ones behaving like children. It started with an idea, but I didn’t know how to make a painting of it. It took a while. I did a few different things that I didn’t like. Then I made this one. Of course, it was also about the fact that Donald Trump was in office. We’re living in a world shaped by this person’s ego and it is a Babyocracy. The idea of putting a child in a grown-up space collided with an actual child being in the grown-up space wearing the president’s suit. I made another one where a child was in the British Parliament.

I suppose one of the things that happens because of your Instagram postings about events in Iran is that it’s easy to look at your work through a political lens. Is that a legitimate way to come at your work?

I don’t think there is a wrong way to come at my work, through that or any other lens. The paintings will give you what they want once you land on them. Not everybody is following my Instagram page. If you look back to October, I wasn’t doing anything with Iran. I’ll probably do more or less in different moments because the work is not going to be happening through this medium. At some point, I wanted to share news that wasn’t being covered by mass media and now the daily news is different. The provocations that are happening in Iran right now are much more akin to Situationist interventions where people are protecting themselves instead of going for an en masse street protest. People are doing more personal actions of civil disobedience. Two guys were arrested because they had painted themselves to resemble dogs, and one was simply taking the other one for a walk on a leash in the streets in Iran, which was completely shocking. While this rather innocent action where both guys were painted from head to toe was not a politicized action, any irregularity is seen as a danger to the system right now. I think there’s a lot to do in this direction. But reading the paintings as having some idea of authenticity is problematic and not what we need as audiences. I think we have become used to reading things historically as opposed to having direct relationships with them. Which is a long way of saying people can do whatever they want to with the paintings. They do what they need to do. We live in an extreme polyphonic space right now where there are so many values, or a lack of any kind of value, and so many other forces are dictating the kind of work that is being made. To me, it is about clarifying one’s values and excavating as a maker.

Love Doctor, 2015, oil on linen, 40.6 × 36.2 × 1.9 centimetres. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures.com. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Projections, 2015, oil on linen, 203.2 × 249.6 × 3.5 centimetres. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures.com. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

It’s telling that you read the events in Iran through a Situationist lens. You did a degree in political science when you were at Oregon, so politics is interesting to you. But reading the Iranian situation the way you do seems to sublimate politics to aesthetics. I like that read, but it’s not what I expected. I would have thought your response would be more directly political.

I don’t think civil disobedience that resembles Situationist actions is sublimating politics. Only last night I thought about the usefulness of naming it as such. Naming it would give people a history to fall back on and a sense of what’s possible, a sense of how that kind of idea can be used to disturb. You seem to like artists. I’m much more realistic. Knowingly or innocently, artists can just take and take and not give anything back. A whole revolution can simply become material for the studio. I’m deeply uninterested in art when it comes to a real-world revolution or climate change, or things that we need to do, like better pay for nurses and teachers. The art thing can become a distraction when it addresses those things because it’s a feel-good pill that allows us to say we’re talking about the right things. I have really high expectations of art and I have very high expectations of political action.

You’ve referred to a certain uselessness in beauty, which sounds like an Elvis Costello song. It reminds me of a larger question about the effect of art in the world. There is a line from Shelley, the English Romantic poet, who says that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” I used to believe that, but now I’m relieved they’re not.

This is a lot to unpack. First, I think that beauty has little to do with art or being an artist. I’m also not entirely sure if releasing the burden of the world from art would make better artworks. There is no formula for good artworks. If Shelley saw the unacknowledged legislators who are running the world today, he might shiver with fright and very well try to occupy that space himself.

For eight years you concentrated on men as the subject of your work. Was an Iranian woman painting men treacherous territory in any way? Was it transgressive for you to even do something like that?

I don’t think Iranian culture was looking at what I was doing at that time. I was certainly not showing it there. I thought about not painting women in the same way that Lee Lozano decided not to speak to women, which was quite a transgressive decision on her part. Sadly, I think we’re not as culturally transgressive as we were in the ’60s and ’70s. It seems in any culture to say women don’t need to be objectified anymore is transgressive because patriarchy knows no borders. It’s 2023 and we are going to have an election of Biden versus Trump? Are you kidding me? These are big structures that operate globally. But at that time not painting women was also the only fruitful thing that I could do. It was the only door open for my imagination until I could frustrate myself to the point of birthing Shit Mom. It’s interesting to frustrate yourself. Self-denial can be very creative.

You have said that sublimating sexual desire was where drawing began for you. Has the notion of sublimation stayed consistent, not just in your drawing practice but in animation and painting?

I was also thinking about this idea of sublimation recently. I stand by that initial experience in my teenage years. But as a teenager, because you can’t get to sex as easily, everything is a sublimation of your sexual desires. Then later you wonder what the sex is sublimating. What else are you interested in doing that is somehow being sublimated? You think it’s all about sex, but it’s actually about this thing and that thing and that other thing. We were talking with some friends recently about Picasso versus someone like de Chirico and how open Picasso was in not sublimating anything in his work. And how maybe the Surrealists needed that linguistic sublimation in order to access themselves. I don’t know where that puts me. I haven’t self-analysed in that way yet. The way that I hold the paintings back from smashing themselves into the canvas is the approximation I imagine that I need with the audience and the figure and what it’s doing to hold their attention. I’m not quite sure what I’m sublimating or what I’m really letting loose. Maybe I’m much more involved with how the work is read than I’m letting on.

Smiley Clean, 2015, oil on linen, 41 × 36.2 × 1.9 centimetres. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

The Ascendant, 2018, oil on linen, 50.8 × 43.2 centimetres.

You know how exaggeration works in the Iranian satirical tradition. A number of your babies and men have phalluses that clearly are in the plus-size tradition of Shunga, Japanese erotic art. I assume we’re not meant to take them literally and that they are a deliberate exaggeration of desire and performance.

The large phalluses are a play on male ego and desire, and sometimes babies with big dicks squishing little men is a meditation on power structures.

A painting like Brown Christmas (2012) takes a symbol of family and happiness and literally sprays it across the room when a Christmas tree is produced from the anuses of the three men. But then in The Santas, you go even further in showing four men standing around the crib of a young boy and urinating. You said earlier that you want to go further, and my guess would be that there are people in both Iran and in the country where you’re now living who would find these depictions outrageous and intolerable. You must know those paintings are pressure points for audience reaction.

Again, I’m imagining my audience in the Western context. But Iranians love humour and there is something about caricature that allows for perversity. Caricature and satire have their own history in Iran; it’s not unfamiliar. But the painting of the four men pissing in the child’s crib has an interesting story. There is or was a law in Sweden, when I had a show at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, against child pornography; this law also covers drawn or painted images, not just photographs/films. And a right-wing politician had taken an image of that painting to court and I was almost sued as a pornographer. But there is this child’s nursery song in Farsi about “How I love my mother because my mother taught me how to walk,” and “My mother taught me how to read” and so on. When I was growing up, kids in school had reversed every single lyric in my mother’s angelic song to things like, “My father put my foot down and always slammed on it,” or “My father peed in my bed and said it was my fault,” or “My father is a shit show and he ruined my life.” So the painting was inspired by these lines. I think whatever shocks Americans shocks Iranians and whatever doesn’t shock Americans doesn’t shock Iranians, either. Whether Americans know it or not, Iranians have also grown up with Madonna, Miley Cyrus and MTV. Pop culture is invasive, right? I think, for better or worse, we all share the same psychological tolerance for certain things. ❚